Despite its title, this Taiwanese manhua has less in common with fairy tales and more with classic English children’s literature, where spunky kids befriend gruff-but-kind adults over a shared hobby or interest. Perhaps the child will help draw the lonely adult out of their shell, while the adult provides the kid with some much-needed emotional support. And would it surprise you to learn that everyone is an orphan with a ludicrously tragic backstory?

We have to start with those ludicrous tragedies, because they weave through and in some cases undercut what is otherwise a lovely little narrative. Within the prologue alone, we watch Helena and her brother almost starve to death, learn their father has drowned in a possible suicide (their mother had already passed), move to an orphanage, and then get separated when Arthur is adopted while Helena is not.

This is all handled with relative restraint, albeit a touch of too-sweet syrup when the kids are telling themselves stories to distract from their hunger. But it turns into accidental parody when Arthur gets into a horrific car crash right in front of Helena mere seconds after they say goodbye. Now the lad is in a coma and everyone knows he’s not going to wake up, but nobody is willing to tell Helena (who deep-down knows, but can’t admit it to herself).

It’s a lot! And without giving away any late-volume plot points, it isn’t even the last terrible accident or tragic twist to plague our characters, one of which features the ableist trope of a person wearing a mask to hide facial scars (although it isn’t discussed in-depth, so it could be resolved positively in the next volume).

Helena and Mr. Big Bad Wolf explores how stories can provide both healthy and destructive escape routes from reality, so it makes sense the cast would have hardships to work through. However, the excessive escalation shoots it off Somber Mountain and straight into Absurdity Gorge, to the point where I caught myself rolling my eyes at the volume’s final “shocking” reveal.

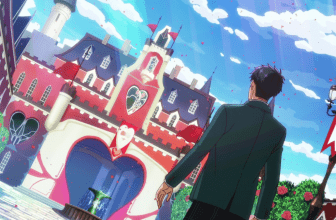

It’s a shame the tragic elements are handled so clumsily, because there really is a lot to like here. Fittingly for its classic kids’ lit tone, the story is set in a vaguely mid-1900s English storybook-land that’s grounded in reality but woven with whimsy. Landen (a.k.a. “Mr. Big Bad Wolf”) wears a wolf’s head in public and everyone takes it in stride; Helena’s imagination turns clouds into pirate ships and subway rides into interstellar travel.

Most of the story is, in fact, quite hopeful and warm, for while Helen’s luck couldn’t get much worse, she’s surrounded by good people who want the best for her. She gets along with the other orphans, the two women who run the orphanage are loving and supportive, and even the irritable Landen is ultimately kindhearted, loaning his picture books to Helena and teaching art to the kids. Her life is not relentlessly bleak, at least.

The big bad wolf has a lot of predatory connotations in folklore, but I’m relieved to announce that’s never even hinted at here. Indeed, the concept of “stranger danger” doesn’t seem to exist in this world, as Helena follows men to their homes without worry from her or the adults. It’s a bit tonally jarring, given all the other darkness in the story, but I’m not complaining if it means I can enjoy Helena and Landen’s sibling dynamic without fear of it devolving into a groomer tale.

Plucky Helena and morose Landen serve as mirrors and foils to one another, as they both hide from the world for different reasons: Helena struggles with her brother’s condition, and Landen worries over how others perceive him and his art. Through their shared passion for picture books, they encourage each other to make human connections and find their courage again.

That shared passion creates some of this volume’s most memorable moments, as this series is, at its heart, a love letter to picture books and the artists who create them. The comic artist themself demonstrates impressive versatility, shifting between a trio of art styles: the main story has a charmingly throwback, slightly messy ’90s shoujo vibe; Helena’s storybooks and flights of fancy are reminiscent of 20th-century children’s comics, especially Peanuts; and Landen’s art evokes more classic, dreamy fairy tale paintings.

These shifts in style burst off the page and help highlight the characters’ relationships with art. For Helena, art is pure imagination and joy, while Landen is deep in a self-doubting slump, fretting about the quality of his work, his growth as an artist, and his ability to convey his ideas to others. The story approaches these dual viewpoints with sincerity and insight, showing that creativity is a hilly journey without a destination, and the only way to get out of a ravine is to keep on drawing.

Much like creativity, Helena and Mr. Big Bad Wolf is itself a hilly journey full of peaks and valleys. When it’s trying to raise the emotional stakes by bludgeoning its characters with tragedy, it stumbles into some muddy pits. But when its likable cast are playing off each other and exploring the challenges and rewards of making art, it climbs to some truly lovely vistas.

I have a fondness for sincere messes, so despite a few eyerolls and even an outright chuckle (I’m sorry, but that car crash was so sudden), the highs still outweighed the lows for me. Whether that’ll be true for other readers may depend on your tolerance for traumatic backstories and plot twists. Still, there’s a lot to love here for fans of wistful children’s literature and picture books, as well as for creatives who have ever struggled through a slump.

This is the first of a two-volume series, and while I get the sense we’re moving towards a happy ending, I also suspect we’re going to have to wade through some deep angst to get there. Even so, I’d like to hop on this hilly road again and see Helena and Landen’s stories to the end. Consider me charmed, mess and all.