More than 61,700 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli forces in Gaza since October 7, 2023, according to an Al Jazeera analysis—and that’s on the higher end of the reported figures. The reported death tolls, which vary widely between sources, are suspected by many to be a significant undercount. They often underestimate (or outright exclude) the many Palestinians whose bodies are trapped under rubble, and they don’t include deaths caused by displacement, injury, or malnourishment—nor do they count Palestinians murdered in the West Bank or in Israeli prisons over the same period. Further, they situate the war in Gaza as an event independent from the century-old history of settler-colonial violence against Palestinians that preceded it. We hear the death toll referenced in news stories, social media posts, and by politicians. Many have become accustomed and even numb to hearing it.

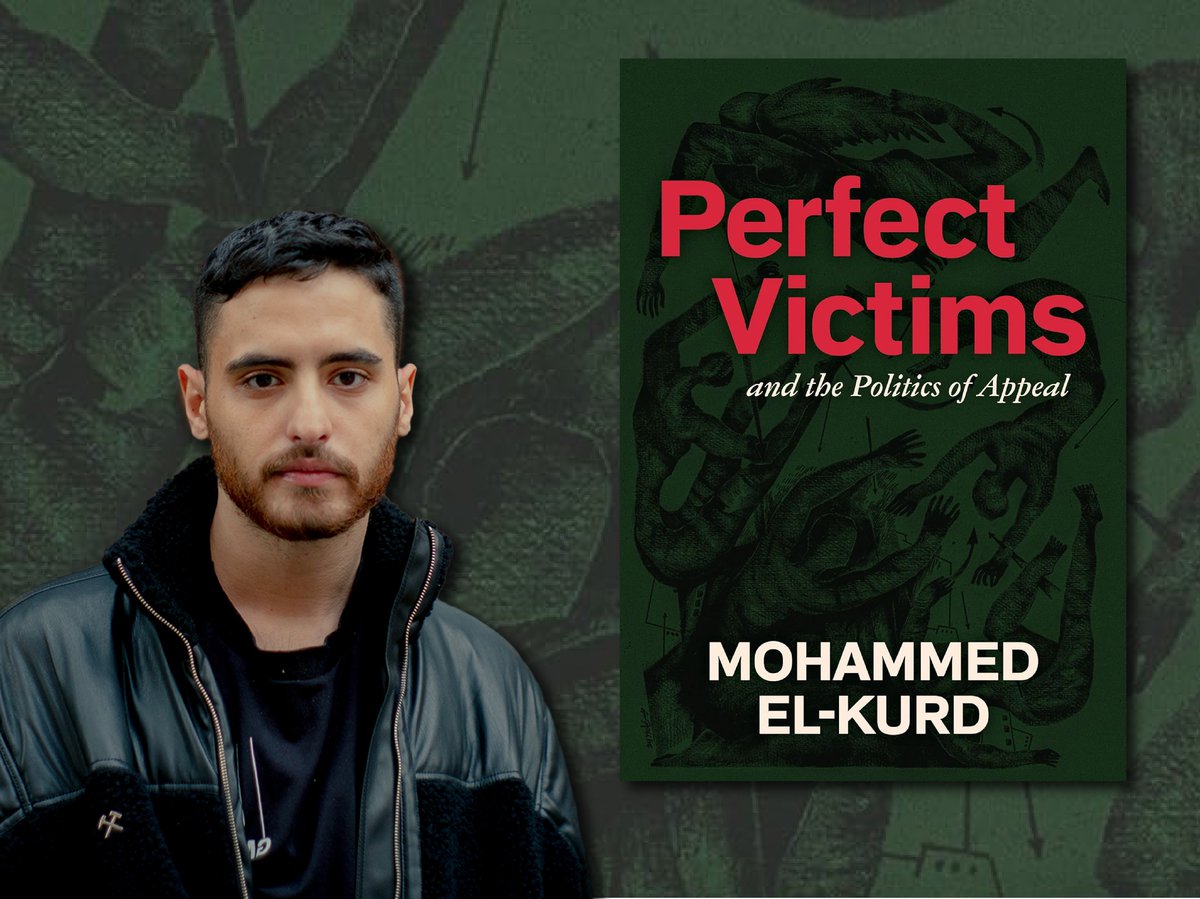

Few people are better acquainted with the West’s collective numbness to the continual death and displacement of Palestinians than Mohammed El-Kurd, a poet and activist from East Jerusalem. At twenty-six, El-Kurd is already an accomplished poet and journalist: He serves as editor-at-large at Mondoweiss and as The Nation’s first ever Palestine correspondent, and published his debut poetry collection, Rifqa, in 2021. In his new nonfiction debut, Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal, he turns his attention to the processes that have manufactured indifference around the world to the ever-growing Palestinian death toll.

Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal

By Mohammed El-Kurd

Haymarket Books, 256 pages

Release date: February 11, 2025

Perfect Victims calls on its readers to toss out not just preconceived notions of who counts as an innocent civilian, but the innocent civilian trope itself. In the West, El-Kurd argues, Palestinians exist in a false dichotomy as either victims or terrorists. The only Palestinians we are compelled to care about are “innocent” Palestinians—the frail and powerless, those deemed unthreatening to Israel, Zionism, and the status quo. This imagined figure, which he calls the “perfect victim,” is just that: an impossible standard.

“Our response to being charged with terrorism, to being ejected outside of the human condition, has been a politics of appeal,” El-Kurd writes. Victims of colonial violence shoulder the burden of proving themselves worthy of humanity through “creative advocacy tactics,” taking care to meet every standard of legitimacy set by those immiserating them even as the goalposts continually shift. “Once the criteria are conquered, magically, marvelously,” El-Kurd continues, “the Palestinian can finally escape the circumscribed category of the terrorist and find refuge in the even narrower node of victimhood.”

By this twisted logic, he writes, “[Palestinians] are not human, automatically, by virtue of being human—we are to be humanized by virtue of our proximity to innocence: whiteness, civility, wealth, compromise, collaboration, nonalignment, nonviolence, helplessness, futurelessness.”

Through this lens, El-Kurd critiques a dominant Western view of the ongoing violence in Palestine that relies on this false categorization, and encourages readers to spend less energy scrutinizing the colonized and focus instead on the abhorrent actions of the colonizer.

“Before I threw the rock, they stole my land,” he writes. “Before I picked up the rifle, they shot my loved ones. Before I made the makeshift rocket, they put me in a cage.”

The book flows freely between sections of reported journalism, personal narrative, and prose poetry. He employs footnotes, both in English and Arabic, to include Palestinian proverbs, citations, and humor—an intentional choice to uplift the teachings that shaped him and reject the pretense that the sole metrics of validity come from international law and human rights organizations. El-Kurd repeatedly uses masculine pronouns to refer to “the Palestinian” throughout the book—in forcing the reader to “come face to face with the Palestinian man,” he hopes to reject the global demonization of Palestinian men.

Among the ideas El-Kurd brilliantly and lyrically ties together is the role the media plays in denying Palestinians dignity and perpetuating the notion of a perfect victim. The standard across industries, he reminds us, is to dehumanize Palestinians. Western publications routinely opt to rely on the expertise of Israeli scholars or international human rights organizations to advocate for the Palestinian cause, for example, rather than affirming and uplifting Palestinian scholars, activists, and everyday people.

In 2022, El-Kurd tried to help a friend, Ru’a Rimawi, publish an essay in a major outlet after her brothers were shot and killed by Israeli forces in their West Bank village. After several rejections, a media expert advised them that the story was getting turned down because Ru’a’s brothers threw stones at the soldiers invading their village. In other words, they weren’t perfect victims.

“Our testimonies have heft, whether published on Israeli websites or not,” he writes. “Our tragedies are real, regardless of whether they are broadcast. Above all, the Palestinian struggle for liberation is heroic—no qualifiers needed. We must not wait for Haaretz or The New York Times to arrive at the miraculous epiphanies we have long called common truths.”

He further critiques the media for often failing to frame stories about Palestine in the land’s proper context—a context of occupation, colonization, brutalization, and displacement—and for too often burdening Palestinians with having to justify their actions or prove why they deserve to live or merely exist.

El-Kurd is at his best when he employs language and ideas that are approachable yet challenging. He argues that pushing people out of their comfort zone is how we progress, and he trusts that the reader will accompany him on the journey. As he writes in his author’s note at the beginning of the book, Perfect Victims “addresses the reader not as a judge but as a curious stranger or better yet a familiar visitor, without fear, jargon, or pretenses.” Its thesis is accessible, with something to offer everyone.

“I do not want us to compare our past to our present,” El-Kurd writes. “I want us to invent a new future, to break out of the hamster wheel.” Perfect Victims pushes us toward this new future—one where our struggles are intertwined, and where Palestinians need not aspire to an impossibly small box of legitimized victimhood in order to deserve dignity and freedom.

“I cannot help but think that this consequential moment calls on us to raise the ceiling of what is permissible,” he writes, “that it demands that we renew our commitment to the truth, to spitting the truth, unflinchingly, unabashedly, cleverly, no matter in what conference room, no matter in whose face.”