What if collecting rare and beautiful objects wasn’t just a uniquely human behavior? A recent study from the Prado Vargas Cave in Spain suggests that Neanderthals—long depicted as brutish, survival-driven beings—may have shared this deeply human impulse. The discovery of 15 marine fossils in a cave occupied by Neanderthals raises a provocative question: Did our ancient cousins collect objects for reasons beyond survival?

The findings, published in Quaternary by Marta Navazo Ruiz and colleagues, challenge the notion that only modern humans were capable of symbolic behavior. These fossils, deliberately transported into the cave and showing no signs of utilitarian use, suggest something far more intriguing: Neanderthals may have been the first collectors in history.

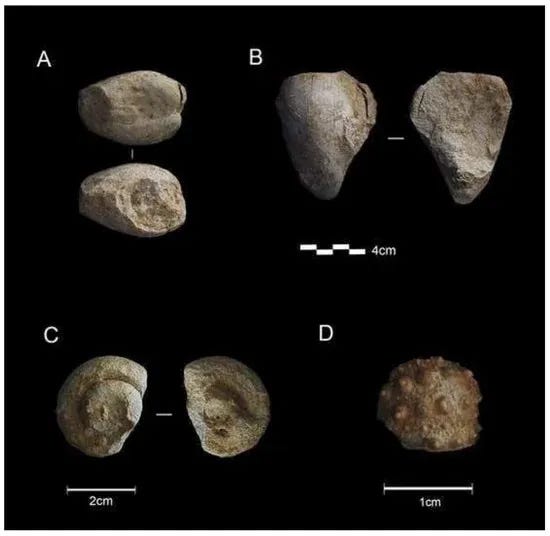

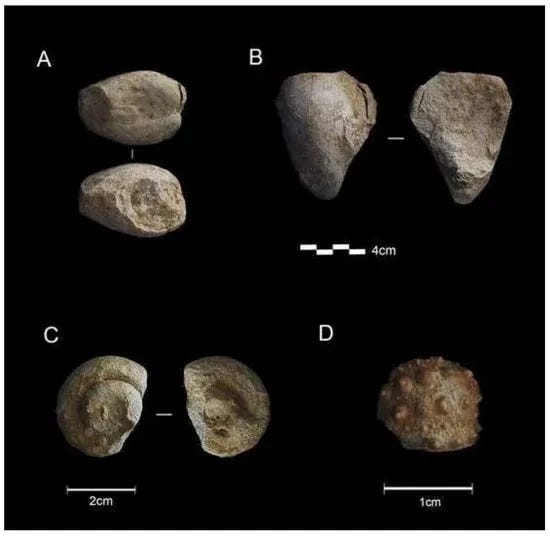

The excavation at Prado Vargas unearthed an exceptional collection of marine fossils dating back to the Upper Cretaceous. Among them were mollusks, gastropods, bivalves, and even an echinoderm—none of which would have had any practical use for a group of hunter-gatherers.

“Fossils, with one exception, show no evidence of having been used as tools,” the authors note. “Thus, their presence in the cave could be attributed to collecting activities.”

This is where the mystery deepens. Unlike isolated fossils found at other Neanderthal sites, Prado Vargas presents the first known example of a deliberate collection. These fossils were gathered from the surrounding landscape and transported into the cave—possibly by children or other members of the group who were drawn to their shapes, textures, or colors.

Why? That remains the unanswered question.

The authors propose multiple theories, each offering a fascinating glimpse into the Neanderthal mind:

-

Aesthetic Appreciation: Perhaps these fossils were simply seen as beautiful objects worth keeping. Just as modern humans collect seashells or gemstones, Neanderthals might have been drawn to their striking patterns and shapes.

-

Symbolic or Ritual Use: Some fossils were found in association with Neanderthal remains, raising the possibility that they were linked to burial or social rituals. Could these fossils have carried meaning beyond mere decoration?

-

Social Exchange or Status Markers: The researchers suggest that fossils might have been given as gifts, traded within or between groups, or used as markers of identity.

-

Children’s Collections: A particularly intriguing idea is that Neanderthal children, much like their modern counterparts, might have enjoyed collecting these objects. The presence of juvenile remains at Prado Vargas strengthens this possibility.

Each of these explanations challenges the outdated perception of Neanderthals as simple beings concerned only with basic survival. Instead, it suggests a species capable of curiosity, creativity, and possibly even an early form of symbolic thought.

This discovery is part of a growing body of evidence reshaping our understanding of Neanderthals. Other sites have yielded pierced shells, ochre pigments, and even engravings, indicating that these early hominins engaged in complex cultural behaviors.

“Collecting activities and the associated abstract thinking were present in Neanderthals before the arrival of modern humans,” the study asserts.

If Neanderthals collected objects purely for the sake of collecting, it suggests an ability to assign value beyond immediate survival needs—an ability that may have been a precursor to art, religion, and other forms of human culture.

The idea that Neanderthals lacked symbolic thought has been steadily eroding. From cave paintings in Spain to the intentional burials of their dead, the Neanderthal world appears increasingly complex.

Yet, skepticism remains. Some researchers argue that while Neanderthals may have collected fossils, it does not necessarily mean they assigned them symbolic meaning. Others caution that more evidence is needed to confirm these behaviors were widespread.

Regardless, the fossils of Prado Vargas stand as a compelling case for reconsidering what we think we know about Neanderthal cognition.

The study from Prado Vargas reminds us that Neanderthals were not simply primitive hunters eking out an existence in Ice Age Europe. They were collectors, observers, and possibly even storytellers.

If collecting is, as some psychologists argue, a deeply ingrained human impulse—one tied to memory, identity, and emotional connection—then perhaps it is time to redefine what it truly means to be “human.”

Did Neanderthals collect simply for the joy of it? Were they drawn to beauty, mystery, and meaning? The fossils of Prado Vargas leave us with more questions than answers, but they also hint at something extraordinary: The Neanderthal mind may not have been so different from our own.

For further exploration of Neanderthal cognition and symbolic behaviors, check out the following studies:

-

Ochre Use by Neanderthals in Europe – DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2021.105388

-

Symbolic Behavior in Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals – DOI: 10.1007/s10816-022-09541-8

-

Neanderthal Burials and Rituals – DOI: 10.1126/science.abb6320