:focal(1000x800:1001x801)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/cb/96cb8e37-e39d-4f47-8beb-43babfa42023/old_town_music_hall_3.jpg)

Audiences of all ages are flocking to Old Town Music Hall in El Segundo, California, for weekend sing-alongs, film shorts and features accompanied by the theater organ.

Old Town Music Hall

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, playing door-to-door Christmas-tree salesmen in sunny Los Angeles, battle an angry would-be customer. Buzz! They yank out the man’s doorbell. Crash! They put an ax through his window. Boom! He blows up their Ford Model T. The sound effects bounce off the walls and vibrate the seats at a recent screening of the 1929 silent comedy short “Big Business” at Harmony Wynelands, an 18-acre winery in Lodi, California.

Experienced organist Dave Moreno creates this whole chorus of sounds—everything from bangs and smashes to familiar tunes like “O Christmas Tree”—on a 1920s theater pipe organ. When you play the theater organ, “you’re the human soundtrack for the movies,” says Moreno.

A century ago, in the heyday of silent cinema and theater organs, audiences would have had a similar experience. “I hate the term ‘silent film’ because they were never, ever shown silent. There was always music,” says Shelley Stamp, a film historian at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The live music engages your emotional response.”

Today, just a handful of places still exist where visitors can be immersed in old Hollywood by watching a silent movie as a talented player tickles the ivories of a historic theater organ. There are opulent theaters in big cities, such as the Orpheum Theater in Phoenix and the Tampa Theater in Tampa, Florida, as well as intimate venues off the beaten track, such as Harmony Wynelands and Shanklin Music Hall in Groton, Massachusetts. Across the country this year, moviegoers can see Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman, Lon Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and other classics.

“If I do my job correctly, people become drawn into the film to the point where they completely forget I’m there,” says Steven Ball, staff organist at the Tampa Theater. “They’re laughing; they’re crying. If they’re startled, I can hear them all jump in their seats.” Playing the theater organ is a fading art—Ball and others estimate there may be fewer than 100 highly skilled players in the United States, and only a handful hold staff positions like his.

Instructions from movie studios in the 1920s about how to score a film were sketchy at best, and few survive. Theater organists develop their own musical repertoires, rehearse with a film, then adapt to their audience. “It’s highly controlled improvisation,” Ball says. “Everything that happens in a good modern film score happens in a silent film score: a main title, a love theme, a chase theme. All this has to be welded together in real time—the creativity limited only by your imagination.”

Theater organs are arguably the world’s largest and most complex musical instruments. They sport multiple keyboards, buttons, tabs and foot pedals that relay electrical signals to release air from a powerful blower to hundreds or thousands of wood and metal pipes—some as long as a city bus and others as small as a drinking straw. The pipes are organized into groups called ranks. Each rank recreates the sound of a single instrument, such as a flute or clarinet. The biggest theater organs have four, five or even six keyboards and more than 3,500 pipes.

The instruments are different from other kinds of pipe organs; they’re louder and make more versatile combinations of sounds. The organist can signal mechanisms that control full-sized percussion instruments like cymbals, gongs, drums and xylophones—as well as “toys” like sirens, train whistles, a barrel of beans to imitate rain and two wooden half-circles that clack together to mimic hoofbeats (think of the coconut shells in Monty Python and the Holy Grail).

Theater organs are built into the fabric of their venues, with components tucked into ceilings and behind walls. The console, where the organist sits at the keyboards, is typically all the audience can see. “It’s about six tons of equipment, but unlike anything in the 2,000 years prior in organ history, it’s designed to be invisible,” says Ball, who also taught at the University of Michigan’s organ department. “This hidden machine was the surround sound of the 1920s.”

Movies were invented in 1895 and were at first accompanied by a pianist in small venues, or multiple musicians in larger ones. Ornate urban “movie palaces” sprang up in the 1910s, with elaborate shows combining vaudeville, newsreels and films—creating a market for something that was loud enough to reach the cheap seats but didn’t require a whole musical ensemble.

Enter eccentric British telephone engineer Robert Hope-Jones. He took a church organ and—like Dr. Frankenstein—electrified its internal action, multiplying the sounds it could make. Theater owners could “have what Hope-Jones called the ‘unit orchestra’ and have one guy instead of 20,” says David Finkel, chairman of the American Theater Organ Society (ATOS). A special seat with one thick, swiveling cushion for each butt cheek kept a theater organist as comfortable as possible as they played in back-to-back shows for eight to ten hours straight.

Despite counting author Mark Twain as an investor, by around 1910, Hope-Jones’s mismanaged theater organ business was in trouble. He sold it to Rudolph Wurlitzer Company of North Tonawanda, New York, whose savvy advertisements and further advances in theater organ design made the organs a must-have for movie houses. “The organs were horribly expensive, but they were there to maximize entertainment value,” says Finkel. “You wanted to escape, and by gosh, that theater organ was going to have you escape.”

Wurlitzer was shipping a theater organ a day by 1926. The organs accompanied some of history’s most beloved movies, including comedies by Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton, and dramas such as The Passion of Joan of Arc, Metropolis and the World War I epic Wings. “People think of silent film as being primitive, and that’s not true—especially in the mid-to-late ’20s,” says Stamp, the film historian. “Some of the greatest films ever made were made during that time.”

“Talkies” burst onto the scene in 1927. By the mid-1930s, films with recorded sound were the standard, making theater organs obsolete. “It was instantaneous,” Finkel says. “Like turning a light switch off.”

Some theater organs were scrapped. Some were boarded up in the walls to gather dust. Experts estimate that of the 7,000 or so built for theaters in the U.S. and Canada, only several hundred remain. According to the U.S. Library of Congress, 75 percent of silent films have also been lost; they were flammable, costly to store and not considered valuable.

The mid-1950s saw a brief resurgence of interest in theater organs. Organist George Wright pressed a popular series of records that makers of top-of-the-line Hi-Fi players used in demonstrations to show off the Hi-Fi’s versatility. Then, the owners of Ye Olde Pizza Joynt in Hayward, California, installed a theater organ to entertain diners—and the short-lived “pizza-and-pipes” craze spread to more than 100 restaurants across the country. This spurred collectors to acquire some organs from movie theaters that were being closed or sold as people shifted from watching movies downtown to watching TV at home in the suburbs.

Enthusiasts founded ATOS in 1955 to save both theater organs and the knowledge of how to play and maintain them. Venues, musicians and ATOS are trying to make these unique instruments accessible for new people to discover—the society holds a regular competition for young organists.

“The reason not many people my age know about [the theater organ] is because they’ve never heard it,” says 20-year-old Fabian Beltran, an up-and-coming organist from Madera, California. “They don’t know it exists. But if they found out, they’d think it’s the coolest, most magnificent thing and they’d wonder why it’s gone.”

A century on, people are paying more attention to silent movies, especially with filmmaker Robert Eggers’ remake of the 1922 film Nosferatu. MacKenzie Mercer, who programs silent film events at the Paramount Theater in Seattle, says the events are drawing record crowds. “There’s a younger generation of cinephiles finding their way to silent cinema,” she says. This new energy may once again revive theater organs, too.

Ball recently donated a theater organ to the Rochester Institute of Technology for a performing arts center set to open there in 2026. “If you put something of great artistic significance, which had this historically important function, in the middle of a bunch of, frankly, the smartest nerds on earth, they’re going to come up with something new that’s culturally relevant,” Ball says. “Like the phoenix, it will again be reborn in a different way.”

Get the ol’ razzle dazzle of theater organ and silent film at these places across the U.S.

Old Town Music Hall, El Segundo, California

Old Town Music Hall Old Town Music Hall/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/44/4e44e662-ad3c-4f77-a2a3-320587c7629d/old_town_music_hall_2.jpg)

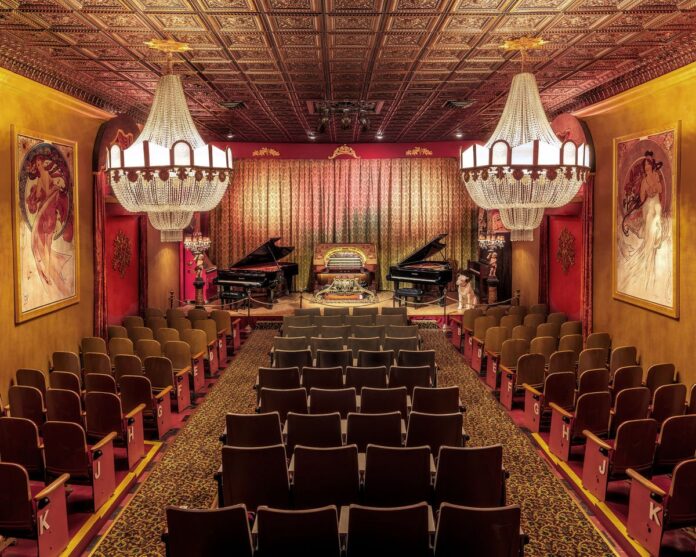

In 1958, friends Bill Field and Bill Coffman scraped together $2,000 to buy the disused Wurlitzer organ from the Fox West Coast Theater in Long Beach, California. A decade later, they bought a run-down theater in the Los Angeles suburb of El Segundo, restoring it with chandeliers they found in a scrapyard.

“This organ was taken out of a hall that seated 2,500 people, and we seat 176. So it’s present and powerful and very close to you,” says Angela Hougen, a board member at Old Town Music Hall and president of the Los Angeles branch of ATOS. The organ’s pipes and percussion instruments are painted in neon colors and sit onstage so people can see how everything works.

Audiences of all ages are flocking to Old Town for weekend singalongs, film shorts and features accompanied by the theater organ. Their next silent film showing is Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman.

“These instruments are built with leather, hide glue and wood. Lack of use destroys them,” Hougen says. “People always say, ‘How on earth do you keep that thing going?’ The answer is, ‘We’ve been running it every weekend for 56 years.’”

Paramount Theater, Seattle

Paramount Theater Jim Bennett/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/0b/cb0b61f7-717f-4c7f-8835-0d6d1517bff2/paramount_theatre_4_co_jim_bennett.jpg)

Quarterly Silent Movie Mondays at the Paramount Theater spotlight films from exactly 100 years ago (hello, Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush!). Some audience members dress as flappers or silent movie stars. An expert guest introduces each film and leads a Q&A afterward, which ASL interpreters translate for an active community of deaf and hard-of-hearing fans.

The Paramount opened in 1928, but by the following year its Wurlitzer theater organ was out of fashion. In the 1990s, the Seattle Theater Group, backed by former Microsoft vice president Ida Cole, renovated the venue and organ. “I wonder: What was it like to be here in 1928? What was the person sitting in my seat wearing? What was their job and family life like?” Mercer, the Paramount’s silent film programmer. “When we show a silent film, it feels like the distance between me and that person is closer.”

Circle Cinema, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Circle Cinema Susan Vineyard/Alamy/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b2/28/b2280e4e-403e-43cb-916c-df19c1cfb36a/2ehbfpn.jpg)

Circle Cinema also opened its doors in 1928, on the old Route 66. It had many chapters in its life as a theater before closing in the mid-1990s. In 2004, it reopened as a nonprofit arts theater with a rotating gallery of works by Tulsa artists gracing its lobby.

Films at the monthly Second Saturday Silent Series are accompanied on an organ built by Robert Morton Company, the second-largest theater organ maker after Wurlitzer. They’re preceded by trivia and sometimes black-and-white cartoons, featuring characters like Felix the Cat. Each year, Circle Cinema partners with the nearby Tom Mix Museum to showcase one of the silent film star’s cowboy flicks; this year it will be 1929’s The Big Diamond Robbery.

Harmony Wynelands, Lodi, California

Harmony Wynelands Heather Ross/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/21/e1/21e18b18-7b0a-46e8-b2de-a86fc7361fa7/dave_moreno_harmony_wynelands_co_heather_ross.jpg)

Harmony Wynelands’ signature vintage is a Zinfandel called Pipe Dreams. That’s fitting for a winery that shows silent movies with the Robert Morton organ originally installed in San Francisco’s Castro Theater in 1922.

Owner Linda Hartzell and her son, chief winemaker Shaun MacKay, greet visitors in the Dutch barn-style structure that houses the organ and serves as Harmony’s theater and tasting room. The organ pipes are visible behind glass. “It stands out as a unique way to experience wine,” MacKay says.

Organist Moreno designed the building with Hartzell’s late husband, Robert, after Robert bought the theater organ in 1987. “The building becomes this living, breathing thing when Dave or another musician plays,” says MacKay.

Shanklin Music Hall, Groton, Massachusetts

Shanklin Music Hall Shanklin Music Hall/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/89/42899dc3-8742-4d86-9e75-d91d6cf5e248/shanklin_music_hall_2.jpg)

Sarah and Garrett Shanklin wanted to preserve a local theater organ for posterity. They acquired the Wurlitzer console that had been in the Metropolitan Theater in Boston and carefully reconstructed the rest of the organ. In 1996, they completed the nonprofit Shanklin Music Hall, which was acoustically designed to help the organ sing.

Their son, Norm Shanklin, who now runs the venue, takes visitors behind the scenes to see the organ’s inner workings. At a screening of Clara Bow’s 1927 romantic romp It, he also arranged a visit from Bow’s white Rolls Royce Phantom. In April, the music hall will be showing 1924’s Peter Pan.

The family’s devotion to theater organs runs deep; a young Norm helped Sarah and Garrett install two of them in their house. “We had trays of pipes under beds—any place was open for grabs,” Norm writes in an email to Smithsonian. “Instead of music on the radio while doing homework, I grew up with the home Wurlitzer in the background.”

Orpheum Theater, Phoenix

Orpheum Theater Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/3b/593bc261-8a0d-4c2d-908b-33ad847b6390/gettyimages-2155741227.jpg)

The Orpheum Theater’s organist, Ron Rhode, cut his teeth playing at roller rinks and at Organ Stop Pizza in nearby Mesa—one of the last operating pizza-and-pipes restaurants. “That was great practice for me,” Rhode says. “People don’t have that opportunity anymore.”

The Orpheum, the last movie palace in Phoenix, opened in 1929. Periodic Silent Sundays film events in the Spanish Revival-style theater unfold beneath a ceiling that changes color from day to starry night, giving the audience the feeling that they’re enjoying the show “al fresco.”

Embassy Theater, Fort Wayne, Indiana

Embassy Theater Nicholas Klein/Alamy/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9f/3c/9f3c4430-626a-49d8-a9a5-7ea4f8b855eb/2x6cyp7.jpg)

Greats including Doris Day, Duke Ellington, Perry Como and Bob Hope graced the stage of this 1928 theater, alongside a theater organ from the small Page Organ Company of Lima, Ohio.

In 1972, volunteers formed the Embassy Theater Foundation to save the building and organ from demolition and raise money to revitalize them. The Embassy has at least five silent films with organ accompaniment planned for this year, including a spooky movie at Halloween.

Tampa Theater, Tampa, Florida

Tampa Theater Tampa Theater/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ed/3c/ed3ce79f-b7a8-42eb-9337-cf0aaff32a42/tampa_theatre_1.jpg)

The Tampa Theater was a thriving movie palace in the ’20s. In the 1970s, it was saved from the wrecking ball and named to the National Register of Historic Places. Its design evokes a Mediterranean town—the stage surrounded by statues and the facades of buildings dripping with foliage.

The venue will host two or three more silent film and organ events this year with staff organist Ball—included as part of its Summer Classics and “A Nightmare on Franklin Street” Halloween film series. Catch a show now, because next year the theater will close for several months of renovations ahead of its 100th birthday.

“The theater organ and its environment are part of our American cultural patrimony,” Ball says. “The key to preservation is the preservation of the whole. The instruments are linked to the film. The film is linked to the theater building. The building is linked to that larger sense of something important that Americans have contributed artistically to the world.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.