:focal(2346x2145:2347x2146)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/73/81/7381412e-6c38-4a42-8faf-02b8e0f12d3d/scan_1.jpeg)

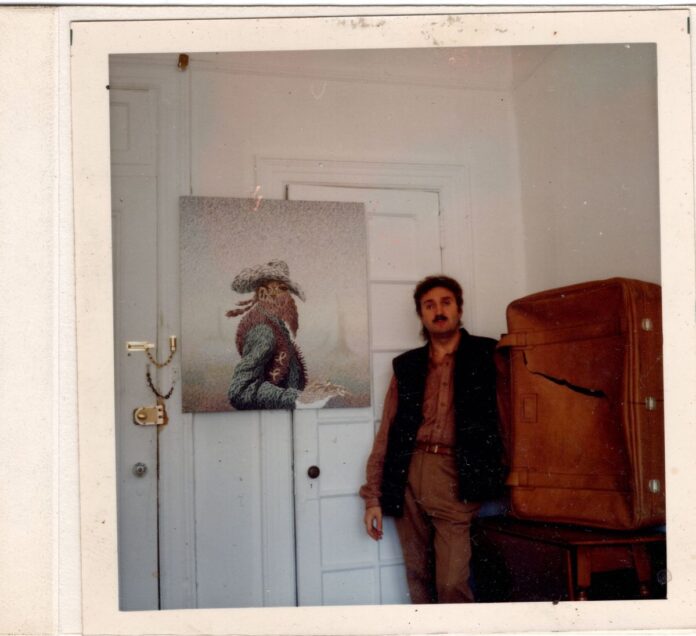

Orlik in the 1980s with The Meek Shall Inherit the World, one of the missing paintings

Winsor Birch

When Grant Ford first saw photos of the swirling Surrealist artworks, he thought they were singular and magnificent.

“They were extraordinary things,” Ford tells the London Times’ Will Humphries. “I was just struck by the pure quality and the style, subject and imagination.”

But the art dealer and former fine arts specialist at Sotheby’s had never heard of the man behind the masterful works, Henry Orlik.

Once upon a time, Orlik was a leading British Surrealist. In the 1970s, his paintings were displayed alongside works by René Magritte and Salvador Dalí at a “Surrealist Masters” exhibition at a top London gallery, according to Artnet’s Adam Schrader.

Subway, New York, Henry Orlik Winsor Birch/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e3/7a/e37a987b-c990-4de0-937e-d6bb60549e6b/subway_new_york.jpg)

But as he honed his craft, including his signature “excitations,” precise squiggles that added texture and complexity to his intricate images, Orlik became disenchanted with the commercial art world and voluntarily withdrew into his private life.

“You look back in history and think had Henry been looked after properly and had he not turned his back on the commercial art world, I do think he would have been a big name in British art,” Ford tells the Times.

Orlik’s health deteriorated over the years. In 2022, he suffered a stroke, which paralyzed the right side of his body. He was living in a housing association apartment surrounded by his artworks, yet unable to paint or make a living.

Henry Orlik with a painting of his mother Winsor Birch/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/24/4f244a47-9520-4f3e-8b3f-22c783ed98cb/henrynow.png)

The following year, Orlik was evicted from his flat in London. In a letter, the housing council said it had “removed and disposed of” his belongings. At least 90 of his canvases are now missing.

“That is a very broad term,” Orlik’s lifelong friend Jan Pietruszka tells the Times. “It could mean they have stored them or sold them or thrown them into a skip. We have asked that question a dozen times and there has been no response.”

Orlik, now 78, is joined by Pietruszka and Ford in taking action to reclaim his paintings and legacy. Over the past year, Orlik’s surviving work has featured in two exhibitions and earned more than $2 million in sales. Now, he’s offering a reward of nearly $63,000 for the recovery of all the missing paintings.

Orlik’s late-in-life rediscovery by the art world has been “very strange,” he tells the Times. “I am very pleased, I suppose.”

Grant estimates that the 90 or so works that were left behind in the apartment are worth at least $12.5 million, assuming they were not destroyed.

“When it comes to the money side, he’s ambivalent, he’s not really interested,” Pietruszka tells BBC News’ Sophie Parker. “The subject always reverts back to, ‘Can you get the paintings back?’”

Parting Dunes, Henry Orlik Winsor Birch/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/c6/75c6c0f0-8c44-403c-b72c-9182d1a8d641/parting_dunes.jpg)

Orlik was born in Ankum, Germany, in 1947. Since his eviction, he’s been living at his childhood home in Swindon, where his family relocated after World War II. His Polish father had fought for the Allied Armed Forces, while his Belarusian mother had survived a Nazi labor camp. The artist studied at Swindon Art College and the Gloucestershire College of Art.

By the early 1970s, Orlik’s works had been exhibited at the Royal Academy and the Surrealist Art Center in London. Among the paintings lost in his apartment are larger-than-life depictions of Marilyn Monroe, reworkings of the Mona Lisa and several paintings of Elizabeth II.

Ford tells Smithsonian magazine that an exhibition of Orlik’s art will open in New York City this summer. Anyone with information regarding his missing paintings is encouraged to contact Ford’s gallery, Winsor Birch.