For decades, research on infant language acquisition has been dominated by studies conducted in what scientists call “WEIRD” societies—Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. These studies have shaped the prevailing notion that infants primarily learn language through direct one-on-one interactions with a primary caregiver, often in a single language. But a new study from Ghana, published in Cognitive Development, challenges this view.

Conducted in Accra, Ghana’s bustling capital, the study by Paul Okyere Omane and colleagues reveals a linguistic reality far removed from the Western nuclear family model. Ghanaian infants, from as young as three months old, are immersed in a multilingual world where they regularly hear between two and six languages, spoken by multiple caregivers in diverse social settings.

The implications of these findings stretch beyond linguistics, touching on anthropology, cognitive science, and the ways we think about early childhood development.

Ghana, like much of Africa, is a land of linguistic diversity. The country has over 80 spoken languages, and multilingualism is the norm rather than the exception. In Accra, the dominant languages include Akan, Ga, Ewe, and Ghanaian English, among many others.

The study examined 121 infants and their caregivers, using a combination of structured interviews and a novel “language logbook” method to track language exposure throughout the day. The results revealed that Ghanaian infants experience a linguistic environment that is as dynamic as it is complex.

Unlike in many Western settings, where a single caregiver—often a mother—plays the primary role in a child’s linguistic development, Ghanaian infants are raised in communal settings, often in large, multigenerational households or shared living compounds. These environments expose them to a steady stream of diverse languages spoken by parents, siblings, grandparents, neighbors, and even domestic staff.

As Omane and colleagues put it:

“The idea that a child learns only one particular language from a single caregiver, as is often assumed in Western cultures, does not apply to these communities.”

Instead, infants in Ghana are embedded in an ever-shifting linguistic landscape, where different speakers may use different languages in different contexts.

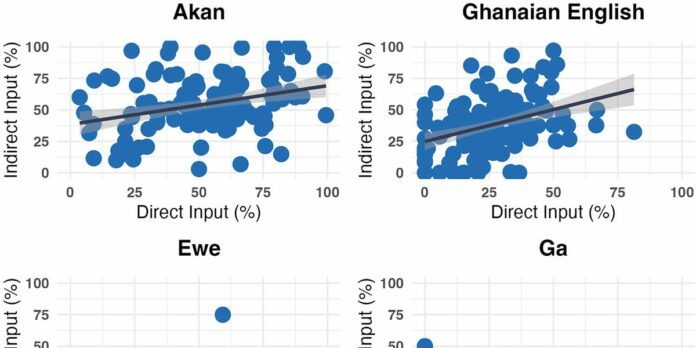

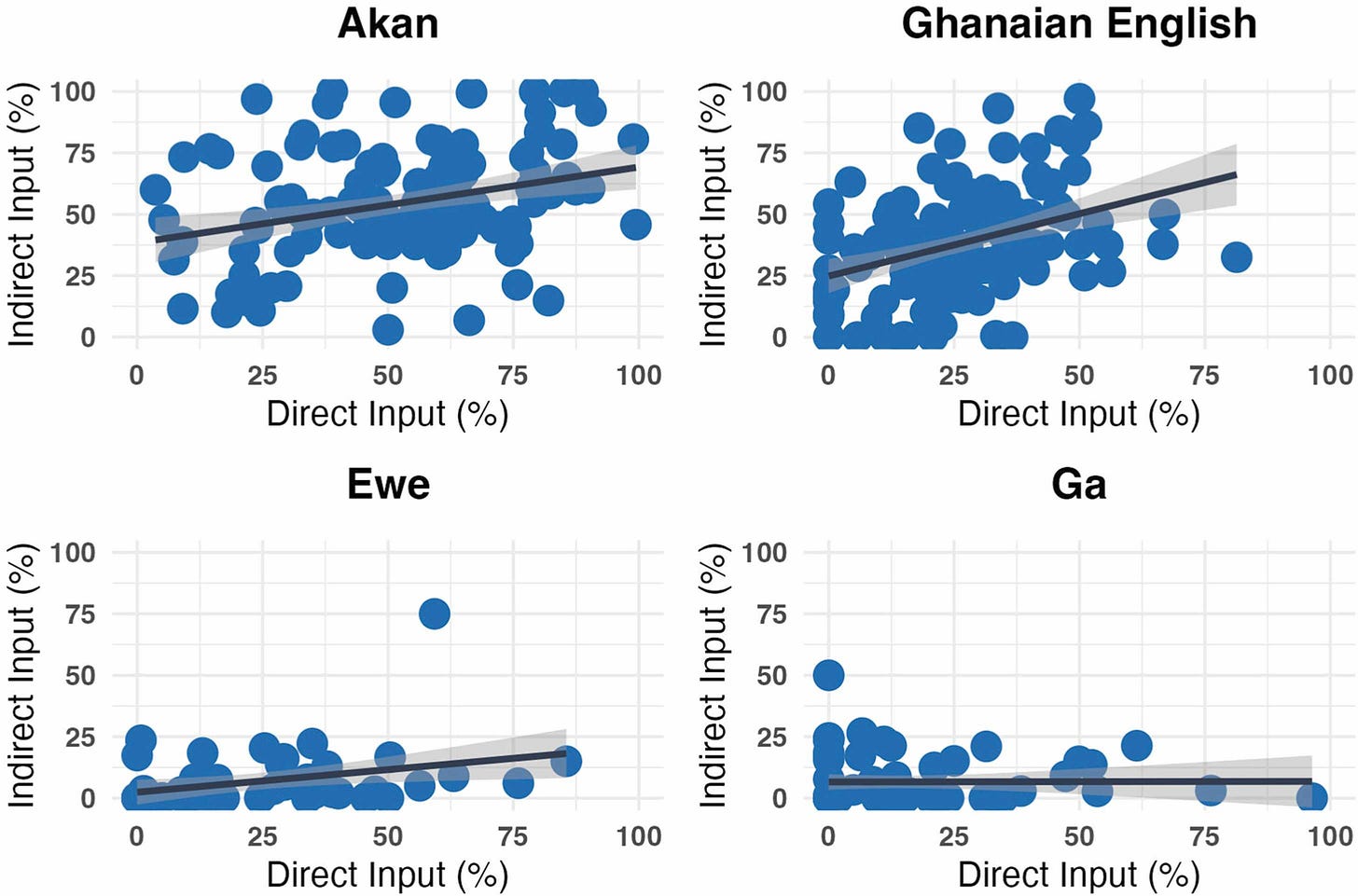

A particularly striking aspect of the study was the distinction between direct and indirect language exposure. While Western models of language acquisition emphasize the importance of direct, interactive communication between caregivers and infants, the Ghanaian infants in this study also absorbed a significant amount of language passively—from overheard conversations, media, and community interactions.

For example, English—the country’s official language—was primarily heard through indirect sources, such as television, official communications, or conversations among adults. In contrast, local languages such as Akan, Ga, and Ewe were acquired more through direct caregiver interactions.

As the researchers explain:

“It is often emphasized how important direct language contact is for language acquisition. However, our results suggest that indirect input—especially through media and official communication—also plays an essential role in the children’s daily lives, particularly in urban contexts.”

This challenges the assumption that infants need to be directly spoken to in order to learn language. In Ghana’s rich multilingual environments, infants seem to be learning simply by being present in a linguistically diverse world.

The Ghanaian infants’ exposure to multiple languages from birth raises fascinating questions about the cognitive and social effects of early multilingualism.

Does this exposure enhance cognitive flexibility? Research on bilingualism suggests that switching between languages can strengthen executive functions such as attention control and problem-solving. If Ghanaian infants are constantly navigating a web of multiple languages, might they develop heightened cognitive adaptability from an early age?

Additionally, the study underscores the deep connection between language and social structures. While Western infants typically acquire language within the confines of a nuclear family, Ghanaian infants are learning in an extended, communal setting. This suggests that early language acquisition is not just about linguistic input—it is deeply tied to the cultural and social fabric of a child’s upbringing.

“Our research shows that for many children, a multilingual environment is a dynamic, vibrant reality from the very beginning. Multilingualism is not just a bonus, but a fundamental part of children’s identity and social structure,” the researchers conclude.

One of the most significant takeaways from this study is its challenge to the dominance of WEIRD-centric models of language development. The vast majority of language acquisition research has been conducted in monolingual or bilingual Western societies, leading to theories that may not hold true in other cultural contexts.

The Ghanaian study suggests that:

-

Multilingualism is not an exception but a default state in many parts of the world.

-

Indirect language exposure may play a larger role in language acquisition than previously assumed.

-

The social structure of a child’s upbringing—whether in a nuclear family or a communal setting—shapes their linguistic development in profound ways.

As the authors emphasize, future research should look beyond Western contexts to build a truly global understanding of how humans acquire language.

“The common assumptions do not reflect the diversity and complexity found in other cultural contexts such as Ghana.”

This is a wake-up call for linguistics and cognitive science: if we want to understand how humans learn language, we need to look at the full range of human experiences.

The study of Ghanaian infants growing up in multilingual environments provides a compelling counterpoint to long-held beliefs about how humans acquire language. Instead of a single, primary caregiver guiding a child’s linguistic journey, Ghanaian babies are immersed in a swirling, communal world of overlapping languages.

This challenges traditional ideas about how early language exposure works and suggests that our understanding of linguistic development has been constrained by a Western lens.

As researchers continue to explore multilingualism in non-WEIRD societies, we may need to rethink what we believe about the earliest stages of human communication—and acknowledge that, for much of the world, multilingualism is not a skill but a way of life.