:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/ef/59ef4b94-0d85-4b9a-90d1-c49db418433c/billy-possum.jpg)

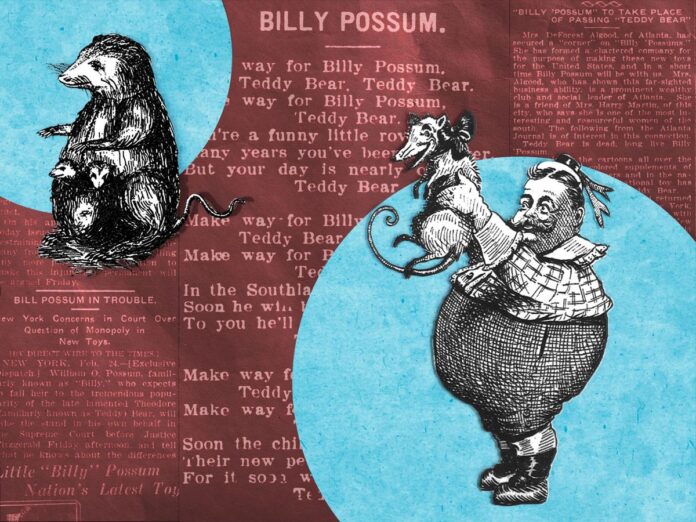

The New Jersey Morning Call said Billy Possum had “a head that is likely to give a baby [a] nightmare.”

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Newspapers.com and Espacenet

“If ‘Teddy Bear,’ why not ‘Billy Possum’?”

That was the question posed by a political cartoon in the January 10, 1909, issue of the Atlanta Constitution.

Inspired by a highly anticipated “possums and taters” banquet that the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce was hosting for incoming President William Howard Taft, the cartoon told the teddy bear to “beat it!” and declared Billy Possum “the new national toy.”

It might seem ridiculous to suggest that the beloved teddy bear, named for the story of Theodore Roosevelt’s refusal to shoot a restrained bear, could be replaced by a plush version of the 18-pound opossum served to Taft for dinner on January 15.

A 1909 political cartoon about Billy Possum versus the teddy bear/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/78/4278b9c0-25aa-4700-93a3-a9fb82f27c36/if_teddy_bear_why_not_billy_possum_original_political_cartoon.jpg)

But where most people saw a joke, wealthy Georgia widow Susie Wright Allgood saw a serious business opportunity. She would take Billy Possum from Georgia all the way to Broadway and the New York Supreme Court, and within six months, she would find the answers to the question “Why not ‘Billy Possum’?”

Allgood and her son Andrew P. Allgood, a Wall Street broker, quickly formed the Georgia Billy Possum Company with an office in the Flatiron Building in New York City. Within a week, Allgood met with patent lawyers, designers and manufacturers to get opossum toys into production in time for Taft’s March 4 inauguration. She planned for each Georgia delegate to wear a little Billy Possum in the parade.

Then Allgood went to work charming the press, quickly becoming the “storm center” of the possum fad, in the words of the Tennessee Journal and Tribune. She demurely referred to herself as “just a plain Georgia cracker,” but outlets like the Journal and Tribune disagreed, calling the 49-year-old “a remarkable woman in more respects than one, the gods having looked upon her with especial favor and partiality … with their gifts of wealth and beauty.” In 1896, the Constitution had reported that she was “notably one of the most beautiful women in the South.”

Susie Wright Allgood/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/ae/baaedf1a-04f7-4ebd-98d5-83a2446bb7d3/service-pnp-ggbain-02600-02667v_1.jpg)

Press coverage of Billy Possum didn’t delve into Allgood’s tragic past, but it would have been familiar to Atlanta readers. An 1898 article in the Constitution noted that Allgood’s personal experiences with loss had uniquely prepared her for her volunteer work during the Spanish-American War, when she attended to wounded soldiers and consoled mothers who’d lost their sons. In 1890, Allgood’s husband, cotton mill owner DeForest Allgood, was murdered by his sister’s husband, leaving his wife to care for their two young children. One of those sons, 5-year-old DeForest Jr., died of croup three years later.

Allgood fully dedicated herself to the success of Billy Possum. She faced a “weird duality,” says Angel Kwolek-Folland, a historian at the University of Florida. “The possum thing is an interesting mix, because it’s a soft toy, which is for kids, except it’s also for politics. You have this national resonance with the political scene.” In 1909, Allgood couldn’t vote—she couldn’t even attend the possum dinner that inspired her business. But here she was, launching a toy as ambitious as she was, a toy the Constitution predicted to be “the petted darling of young America, the fad of the modish woman and the mascot of the incoming administration.”

A “possum and taters” dinner served to incoming President William Howard Taft in January 1909/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/70/08/7008d8b3-1779-4425-8205-7ee189d97c46/possum_dinner.jpg)

Both Allgood and her son Andrew came up with some innovative ideas to market Billy Possum. Most of the publicity was handled with live opossums under the bold assumption that seeing the creature in person would help. Billy Possum’s first stop was Broadway.

In an early form of influencer marketing, Allgood arranged for a live opossum to appear onstage with Anna Held, Broadway’s most popular musical comedy star. The actress was a pioneer of publicity stunts and product endorsement. Fans could buy Held-branded corsets, face powders and cigars. She had previously appeared onstage with life-size teddy bears, so she was the perfect choice to reveal the stuffed animal’s successor. Held walked out with the opossum during the last verse of her number “I’ve Lost My Little Brown Bear”—a surprise said to bring down the house.

Anna Held performing with teddy bears in 1906 or 1907/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d7/99/d799688e-97c1-4031-af58-f7edac24bac1/anna-held.jpg)

Meanwhile, Andrew was working behind the scenes to popularize the possum in his own way. According to the press, he put together a “real possum party” at the King Edward Hotel in New York for the chorus girls of The Queen of the Moulin Rouge, a risqué show with song titles like “The Pleasure Brigade” and “Take That Off, Too.”

The evening kicked off with a “christening party” where two live opossums were dipped into a punchbowl of champagne. This was followed by a supper of pickled possum, possum soup, roast possum and possum pudding, and capped off by a “kissing party” where each girl “paid her respects” to the surviving opossums, a wire service reported.

This rare Billy Possum toy sold at auction in 2005 for £1,560./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/57/04/57048270-c734-4958-985d-7743e9646b5e/screenshot_2025-02-14_at_25411pm.png)

The publicity stunt inspired headlines like “‘Possum Meat Am Good to Eat,’ Say Girlies Sweet,” but the stories failed to mention the Allgoods’ company or its stuffed toy.

Another aspect of Allgood’s marketing plan was the publication of a Billy Possum book, touted in the press as the next “national child’s book.” In the spirit of Joel Chandler Harris’ popular Uncle Remus stories, in which the formerly enslaved title character recounts African American folktales of animal characters such as Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox, Allgood planned to make a photobook that would lean into Southern stereotypes about eating possums that were rooted in white supremacy.

Allgood recruited a friend, poet Leonora Monteiro Martin, to write the book’s text and accompany her in taking original photographs. As Martin told the Knoxville Sentinel, “I met every possum in Georgia, and Mrs. Allgood and myself had some unique experiences touring the country in the neighborhood of Atlanta looking for typical Negro types and for possums.” The book was never published, but Allgood copyrighted several photos, some of which were published in a spread in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

By the end of January 1909, the Georgia Billy Possum Company was producing thousands of opossums advertised in three somewhat confusing sizes: life-size, medium and four inches long. Allgood had innovative plans for a new version that took advantage of the marsupial’s unique anatomy, patenting a “toy in the form of an opossum carrying its young” that would feature a pouch full of baby opossums.

Almost as soon as production began, it stalled when Billy Possum landed in the Supreme Court of New York. The Allgoods accused one of their manufacturers, Harry Nadler, of violating their exclusive contract and making Billy Possums for other companies. In late February, the judge issued a temporary injunction barring Nadler from making possums for anyone except the Georgia Billy Possum Company.

Allgood’s patent for a Billy Possum toy/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/8a/618a256b-0974-4020-ad66-eb6945f8a83f/gb_190907496_a.png)

Just over a month later, on April 1—a night some children would never forget—a fire broke out at Nadler’s warehouse in New York’s Greenwich Village neighborhood.

Firefighters climbed to the top floor of the building to battle the blaze but found their path blocked by boxes of stuffed toys. They cleared the way by dumping hundreds of stuffed animals out the sixth-floor windows. According to newspaper reports, neighborhood children flocked to the scene to see the flaming teddy bears rain down upon Wooster Street. They eagerly scooped up the scorched, smoky bears. Opossum toys went unmentioned in the reports.

Nadler’s company filed for bankruptcy, and its remaining inventory of Billy Possums, teddy bears and other toys was sold at auction.

By May 1909, the future of Billy Possum looked bleak. Production problems aside, Billy Possum just wasn’t selling. There was little demand and stiff competition, especially when the German toy company Steiff debuted its own Billy Possum, albeit reluctantly.

“I don’t believe in mixing toys and politics,” Richard Steiff, the nephew of the company’s founder, told the American Stationer in 1912. He had designed a stuffed toy bear in 1902, before the teddy bear became associated with Roosevelt. “But they kept at me to make the ‘Billy Possum’ and then nobody wanted it.” The company sold 10,028 units in its first year but only a few hundred over the next several years.

An advertisement for Billy Possum/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d4/dc/d4dcd004-5d41-496f-9ede-7199b240f67c/billy_possum_advertisement.jpg)

Original Steiff opossums are in high demand today. “I’ve handled a couple in terrible condition, and they still bring in five grand,” says Rebekah Kaufman, a historian of the Steiff company. “That’s how rare they are.”

Steiff believed aesthetics were to blame for the toy’s failure. “The American youngster instinctively turns away from what is ugly or grotesque,” he told the American Stationer. “That was the trouble with the Billy Possum—it was too ugly an animal.” As Kaufman explains, Billy Possum was “so out of [the company’s] purview of the aesthetic of what they were making.”

That seemed to be the consensus. Allgood’s beauty may have been legendary, but the toy she championed was considered repulsive. The New Jersey Morning Call said the stuffed opossum had “a head that is likely to give a baby [a] nightmare.”

It looks “too much like a rat, is the complaint we get,” one toy importer told the Spokane Press. “They don’t go worth a cent. The kids won’t stand for ’em. … And we spent thousands of dollars on the chance that they would be a hit.”

In July 1909, just six months after Allgood launched her company, the Spokane Press declared, “Billy Possum a Failure but Teddy Bear Still a Joy With Little Ones.” That same week, Allgood, who had just sold 12 lots of her late husband’s Atlanta property for $82,267.70 (nearly $3 million today), left for Europe.

Billy Possum lived on during Taft’s presidency in songs and postcards—ephemera that did not depend on a child’s affection—and even made a brief return to politics. In 1929, President Herbert Hoover adopted a wild opossum found wandering the White House grounds and named it Billy Opossum.

When Allgood returned to the United States in the fall of 1910, she found herself in the papers once again, this time as a “woman smuggler.” The U.S. Customs Service accused her of grossly undervaluing her imported Parisian gowns, and her trunks were held for more than five months until the duties issue was resolved.

When she finally got her attire back, Allgood threatened to sue the government for damages, saying it had kept her clothes for so long that they were no longer in fashion.

She knew, better than most, that no amount of effort, money or marketing could force something to be in style.

A 1909 newspaper article about Allgood and Billy Possum/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b2/9d/b29d5f25-be69-49ea-8f01-cc70ed0948cd/the_kentucky_post_1909_02_06_6.jpg)