Article begins

For Muslims of the Arab world and Jews, whose religious life can be so closely identified with Arabic and Hebrew respectively, it is striking that a French community of Tunisian-descended Jews are working to remember the Tunisian Judeo-Arabic that their parents and grandparents had tried to forget when they migrated to France following Tunisia’s 1956 independence. In this column, I discuss some of the ways that French Tunisian Jewish descendants are remembering and revitalizing Tunisian Judeo-Arabic and how these practices can unsettle assumptions about the relationship between migration and language shift.

Following independence, suspicions concerning the loyalty of Tunisian Jews to the newly independent state as well as regional political tensions surrounding the 1967 Arab-Israeli war led to the majority of Tunisian Jews migrating to France. There, the pressure to integrate into French society at large, as well as into an already established Ashkenazi Jewish community, involved the assumption that these new immigrants would stop speaking Tunisian Judeo-Arabic and that their descendants would grow up as monolingual French speakers. This assumption is in keeping with many commonsensical understandings of language shift in migration as described by Joshua Fishman in 1966. At first glance, this is exactly what seems to have happened; today, virtually no descendants of Jews from North Africa describe themselves as Arabic speakers. However, this does not mean that they have lost interest in the language and traditions of their parents and grandparents.

Among French Jews of Tunisian descent, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in their ancestors’ lifestyle before migration and with their cultural and linguistic heritage. One major way in which they are challenging the assumption of language loss and reclaiming the Arabic part of their Judaism is through lessons at an Arabic-language learning association. Founded in 2019 by two Arabic and Hebrew professors and descendants of North African Jews, the association aims at helping other descendants of North African Jewish immigrants discover and share their linguistic heritage. At first, the association offered standard Arabic lessons. However, in response to demand among members of the association, they now also offer a course in Tunisian Judeo-Arabic as well as a course on the Pessah Haggada, a Jewish text used during the Passover holiday and written in Tunisian Judeo-Arabic. In addition, these courses are accompanied by community events, such as a religious community dinner celebrating the holiday of Pessah/Passover in the traditional Tunisian Jewish manner.

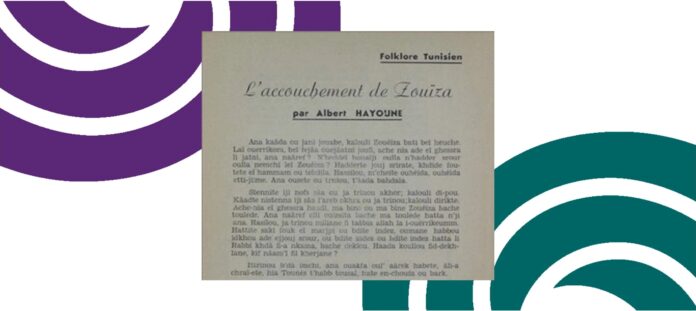

In addition to this cultivated embrace of their linguistic heritage, many members of the French Tunisian Jewish community are also discovering that their ties to the language of their parents and grandparents have been alive all along in ways they had not necessarily recognized. I first came to this realization by accident. I was flipping through the 1955 Directory of Jews in Tunisia—the Annuaire Israélite de Tunisie—a compilation of information such as the members of the Jewish Council; the names, addresses, and phone numbers of various religious and social services; and advertisements for Jewish-owned shops. As I browsed through it, I stumbled on a strange section at the end. It read, “Tunisian Folklore, Zouïza Is Giving Birth” (Folklore tunisien, l’accouchement de Zouïza). A short story, it is the only section of the Directory in Tunisian Judeo-Arabic and is written in the Latin alphabet. Surprised, I showed the story to a man who was to become my first interviewee: a native speaker of French in his mid-50s whose parents were born and raised in Tunisia. He claimed to have no competency in Tunisian Judeo-Arabic. However, his eyes started filling with tears as he discovered that not only could he pronounce the text before him like his parents used to pronounce Arabic while speaking to one another, but he could also understand and translate most of it. In a recent interview, he described this moment of rediscovering Tunisian Judeo-Arabic as a “destabilizing experience,” as if he had “a whole language buried inside” of him, ready to use without really knowing that it was in there or how to get it out. I realized that sometimes people may not think of themselves as “speaking a language” but can nonetheless have remarkable linguistic competencies. As a member of a French Jewish family of Tunisian descent, this encounter left me wanting to know more about Jews from North Africa, about their relationship to Arabic, and about what that could teach us about both language competency and about colonialism and migration.

First page of the short story Zouïza’s Delivery by Albert Hayoune. The section’s and story’s titles are in French : Folklore Tunisien. L’accouchement de Zouïza but the story in itself is written in Tunisian Arabic using latin characters. The transcription does not follow the academic standards for Arabic taught in French universities nowadays. The author wrote the sounds of Arabic as closely as he could. Some Tunisian-Arabic jewish speakers sometimes write jokes this way on social media still.

Credit:

Creative common license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Nataf, Victor. Annuaire israélite de Tunisie. 1955. Bibliothèque de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle, cote 8UBR5086. https://www.bibliotheque-numerique-aiu.org/idurl/1/16170

The Directory is, in itself, an interesting document for understanding the language practices of the Jewish community just before Tunisia’s independence in 1956. Published annually, it can be read as a record of a thriving Jewish community that was literate in French. While they were not literate in Arabic, the use of Latin script to transcribe Arabic sounds informs us of the ongoing presence of Tunisian Judeo-Arabic in the Jewish community at least until independence and most probably until they left the country in the 1960s. The story of “Zouïza Is Giving Birth” at the very end of the directory indicates that Arab folklore or minor news items were of interest within that community. In addition, the use of Latin characters suggests that Arabic was primarily used for oral communication and informally taught. Meanwhile, the subject of the story shows that the topics were mainly about “kitchen-table issues,” that is, matters concerning family and everyday life.

Arabic-speaking Jews brought those language practices with them from Tunisia to France and tried not to transmit them—but partially failed in this regard—to their children born or socialized in France. In this context, Tunisian Judeo-Arabic became a code, a cryptolect, among parents to address adult matters. It also served as a code for discussing things having to do with the kitchen, since fruits and vegetables shops were usually kept by Arabic-speaking Muslim Tunisians in Tunisia and often by Arabic speakers from Maghreb in France. Tunisian Arabic thus became a means to create commonality or even sometimes identity with Muslim Tunisian immigrants in France. In large part, Tunisian Judeo-Arabic is fairly well-preserved despite commonsensical expectations of language loss because many traditional cultural aspects of Tunisian Judaism were and still are conveyed in this sociolect. For example, the names of holidays, traditional dishes, and piyyutim (religious poems) are all taught in Tunisian Judeo-Arabic even though the religious sacred texts and prayers are in Hebrew. Judeo-Arabic was passed on as part of a Tunisian tradition of Judaism more than as a Tunisian heritage at large, and it differentiated Jewish Tunisians not only from Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi communities but also from other Judeo-Arabic-speaking communities from North Africa. Today, whether or not they think of themselves as “speakers of Tunisian Judeo-Arabic,” these are the linguistic and cultural practices that usually remain alive within the families of French Jews of Tunisian descent. In other words, their Arabic heritage is part and parcel of their Judaism.

Through the lens of ethnography and linguistic anthropology, the case of Tunisian Jews sheds light on the dynamics of language preservation, loss, and reclamation in migration. It challenges conventional understandings of language attrition, offering a nuanced perspective on the enduring ties between language transmission and cultural memory. And it points to the often overlooked ways in which linguistic practices can serve to create connections across stark social divisions.

Sarah Muir and Courtney Handman are the section contributing editors for the Society for Linguistic Anthropology.