by Marc J. Randazza

Introduction

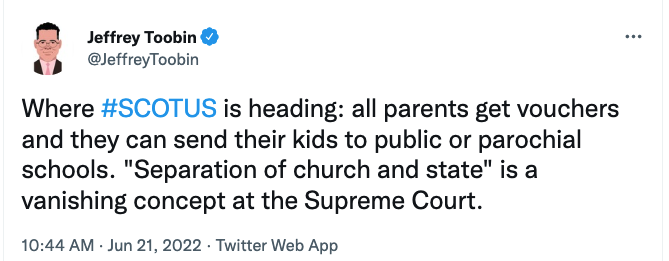

The Supreme Court issued a decision this week in Carson v. Makin, and the commentary from the Left seems to be that the sky is falling and that it will usher in the Handmaid’s Tale. My friend Elie Mystal believes that this means that the wall between church and state is falling. (here) He is not alone.

The American Federation of Teachers had this to say:

“Remarkably and stunningly, even for this right-wing majority, this decision completely vitiates the establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution and, with it, the separation of church and state, a core constitutional principle that has bound this country together since its founding. Today the court has decided that taxpayers must pay for the private religious education of others. (source)

The predictions of disaster are, I think, overblown. I think the American Federation of Teachers is quite simply lying to you.

The Case

The Maine Constitution requires that all children are entitled to a free public education. However, fewer than half of Maine’s school districts operate a public secondary school. Therefore, if a child lives in a district where there isn’t one, then the government pays tuition assistance for them to attend private schools – as long as they meet certain educational requirements.

But, in 1981 Maine passed a law that excluded any religious-oriented school from the program. This was because the Maine attorney general believed that failing to do so would violate the Establishment Clause. In all fairness to the Maine attorney general, the law may have been a bit unclear on this. But, in 2002, the Supreme Court held that a benefit program where private citizens directed government aid to religious schools as a “genuine and independent private choice” was not contrary to the Establishment Clause. See Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U. S. 639 (2002) Then, Maine considered repealing the limitation, but it did not pass.

The Court explained that the Free Exercise protects against “indirect coercion or penalties on the free exercise of religion, not just outright prohibitions.” Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Assn., 485 U. S. 439, 450 (1988). The government violates the Free Exercise Clause if it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits. “A neutral benefit program in which public funds flow to religious organizations through the independent choices of private benefit recipients does not offend the Establishment Clause” (Op. at 10)

As the court explained, the government must be neutral in matter of religion. But, in this program, there was “nothing neutral” about it – the State of Maine would pay for private school tuition, as long as the school was not religious. “That is discrimination against religion.” (Op. at 10)

The decision relies upon two prior cases, which fit squarely within its facts. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012 (2017), the Court considered a Missouri program that offered grants to qualifying nonprofit organizations that installed cushioning playground surfaces, but denied such grants to any applicant that was owned or controlled by a church, sect, or other religious entity. There, the Court held that the Free Exercise Clause did not permit Missouri to “expressly discriminate against otherwise eligible recipients by disqualifying them from a public benefit solely because of their religious character. The crux of Trinity Lutheran,and the Court’s jurisprudence in this area since, was that the religious organization was required to renounce its religion in order to receive public funding.[1]

In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2261 (2020), the Court held that a provision of the Montana Constitution barring government aid to any school “controlled in whole or in part by any church sect, or denomination” violated the Free Exercise Clause by prohibiting families from using otherwise available scholarship funds at religious schools. Following the policy in Trinity Lutheran, Chief Justice Roberts writing for the majority stated that “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

So what’s the big deal?

If the government gives you a benefit, it can’t limit that benefit in a way that would offend the First Amendment. Remember in Matal v. Tam, the trademark office once banned registration of trademarks that were “disparaging.” The government said that this is because they were just offering a government benefit, not engaging in censorship. The doctrine of unconstitutional conditions required striking down that restriction. This is similar – the government can’t say that you can attend any school you want on the state dime, as long as they do not teach you religion in addition to the state requirements.

This does not mean that the state can directly fund religious schools. This means that if the state gives you a choice, that choice can’t be limited to non-religious schools only.

And despite this perspective, which is also dishonest, this does not mean that this applies to Christian schools only.

Mr. Ali, and those fawning over his statement seem to believe that the issue here is Christianity vs. other religions. However, he would be precisely wrong. If you can’t discriminate against religion itself, you can’t discriminate between religions.

Now remember the American Federation of teachers’ statement at the top? Their statement continues with “Now more than ever, we must prioritize our public schools, not marginalize them; we must invest in them, not divert money away to private programs.” (emphasis added)

So what are they really worried about?

Competition.

[1] Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2024 (2017)

The State in this case expressly requires Trinity Lutheran to renounce its religious character in order to participate in an otherwise generally available public benefit program, for which it is fully qualified. Our cases make clear that such a condition imposes a penalty on the free exercise of religion that must be subjected to the “most rigorous” scrutiny. Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520, 545 (1993)