:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/3f/4e3f1dee-6971-4f9a-9305-de41197ab84f/martha_s_jones.png)

Historian Martha S. Jones (bottom left) turned to ledgers, deeds, census records and government documents to unravel her family’s story.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Photos courtesy of Martha S. Jones and Johns Hopkins University

Nancy Bell Graves gazed out boldly, bonnet trimly tied as she posed for the bright studio flash. A book lay open on her lap. At age 80, she was a mother many times over, as well as a survivor of slavery. Baptismal registers and legal documents whisper snippets of her life story: Born in Danville, Kentucky, in 1808. Joined a Presbyterian church in 1827, then found a new home in the Methodist movement. Helped her children battle for their freedoms. Petitioned for her husband’s Civil War pension.

For years, Nancy’s photo hung over the desk of award-winning historian Martha S. Jones, raising more questions than answers. “She was an enslaved woman who bore many children, including a daughter who was the grandmother to my grandmother,” writes Jones in her new book, The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir. “Nancy bequeathed to us not only her portrait but also the trouble of color—somewhere between too little and too much of it.” Intrigued, Jones—the child of a white mother and a Black father—dug into her family’s past. What did it mean to be “a daughter of Nancy”?

Genealogical discovery calls for thorny detective work. Dense records can hide facts. Fragments of photographs can illuminate lost moments. What can we trust to reveal our ancestors’ lives and choices? On her quest, Jones trawled through thick college archives and made difficult plantation visits. She parsed stray census notes and starkly written deeds. When research leads twisted or sputtered out, she drew clues from conversations, memories and keepsakes.

Jones followed Nancy’s story forward, chronicling several generations to reach the present day. “Everywhere, I began to see Nancy’s face in my own: olive, red, yellow, as I’ve been termed by loved ones and foes alike. I wondered what Nancy was called,” Jones writes. “In her time, long before colorism and passing, before white-presenting and brown-paper-bag ideals, before antimiscegenation laws and Loving v. Virginia, Nancy knew something of how we came to be women mixed, mulatto and migrants along the color line.”

A scholar at Johns Hopkins University, Jones is the author of multiple acclaimed books on African American history. In addition to teaching, she directs the Hard Histories at Hopkins Project, an initiative committed to a “frank and informed exploration of how racism has been produced and permitted to persist” within the university structure. She has also served as an adviser and consultant to such cultural institutions as the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, the National Women’s History Museum and the Library of Congress.

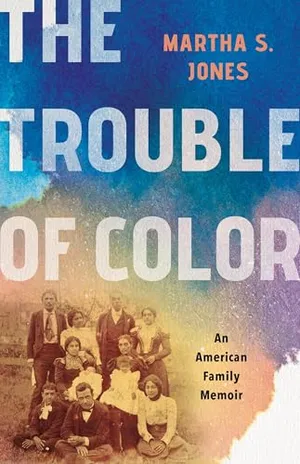

The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir

Journeying across centuries, from rural Kentucky and small-town North Carolina to New York City and its suburbs, “The Trouble of Color” is a lyrical, deeply felt meditation on the most fundamental matters of identity, belonging and family.

In All Bound Up Together, Jones traced the multigenerational stories of Black women activists. In Birthright Citizens, her Baltimore-based saga of the 14th Amendment’s long legal history, she showed how, from “the local courthouse to the chambers of high courts, the rights of colored men came to define citizenship for the nation as a whole.”

More recently, in Vanguard, Jones charted the paths that African American women carved to gain political power. Nancy’s memory was a prompt. “I wondered what it had been like for Nancy’s daughters and granddaughters when, in 1920, the 19th Amendment opened a door to women’s votes,” Jones wrote in her 2020 book. “That year, three generations of women in my family—from my grandmother to her mother to her mother’s mother—faced the same question: Could they vote and, if so, what would they do with their ballots? And though I knew lots of family tales, I’d never heard any about how we fit into the story of American women’s rise to power.”

Writing a memoir offered Jones a unique window onto the complexity of her own roots—and a chance to talk back to the past. To mark The Trouble of Color’s release on March 4, Smithsonian spoke with Jones about the power of producing a memoir, and how something as fragile as a teacup can be a touchstone. Read on for a condensed and edited version of the conversation.

How did you start researching The Trouble of Color?

When it comes to research, I’ve been collecting material for this book for almost my entire life. I’ve long been a pack rat and an avid family historian, so what you call research has been a part of my day-to-day habits for a long time. Not very long ago, I found a note from my grandmother among my keepsakes that included a newspaper clipping about my grandfather. I was just 18 months old when she wrote the note. You could say that my grandmother got me started, safekeeping little things that were important to me and to us as a family.

Why did you write The Trouble of Color as a memoir?

Deciding to write a memoir came much later. First, I learned to write books as a historian. I cared deeply about those stories, but I also told them from a studied, professional distance. When I tried to write about my own family in that same way, I kept failing. Something was missing, and over time, I discovered that something was me and my point of view. Memoir permitted me to fully enter the story of my family past: as a descendant, as a researcher and as a storyteller. My histories help readers arrive at how to think; this memoir invites readers to also reflect on how to feel.

The Jones family in Greensboro, North Carolina, circa 1900 Courtesy of Martha S. Jones/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/8c/ae8cdfcb-a247-4ac8-8f7e-dd45f27bc7cc/jones-family-in-greensboro-ca-1900.jpg)

Tell us about Nancy Bell Graves and your great-uncle Robert E. Jones, whom you refer to as the Bishop. How did your view of the Bishop change?

Nancy’s family story is the first puzzle I confronted in The Trouble of Color. From her, I had only a photograph and the application she made for her husband’s Civil War pension. These were a start, but before I was done, I came to rely on a string of memories of her passed down by her daughters; I learned to trust those recollections. I also turned to the ledger books left behind by a man who enslaved Nancy. I can’t say I ever learned to trust him, but his notes did permit me to connect Nancy to long-forgotten kin.

The Bishop was a leader of the Methodist Episcopal Church and a storyteller who never managed to complete his own autobiography. Instead, he recounted his family story to a historian, who later published it in a book called The Negro Vanguard. Though I never met him, I was raised to think of the Bishop as a patriarch; he was many years older than my grandfather, his baby brother. Still, I discovered that the stories he’d told were selective. This meant that he left out some important details, like his own grandmother’s enslavement. I began to see him less as an authority to be deferred to and more as a man who told the stories he’d needed to tell in his own time. The Trouble of Color is partly me talking with and back to him.

In tracing the lives of your 19th-century ancestors, you emphasize that their bodies were enslaved but their minds were free. How did you bring that message home?

That battle—for freedom of the person and of the mind—fascinated me while writing The Trouble of Color. Susan Penman Davis, my grandmother’s grandmother, was for a time hired out to a minister and college president. She was obliged, as an enslaved woman in the antebellum South, to labor in his household for him, his wife and his children. The same man regarded Susan’s mind as a sort of experiment: He taught her to recite grand literature such as the poetry of Lord Byron, but he never schooled her for life after slavery’s abolition.

A teacup once owned by Jones’ grandmother’s grandmother Martha S. Jones

Today, I have in my home a set of French china, Haviland, that Susan used as a free woman to serve family and friends in her own home. The set was passed down across generations, and for me, it acts as a reminder that she finally got closer to freedom, eventually making her own family and keeping her own home. Each time I hold her cups, I can almost imagine Susan there, pouring tea, trading gossip, and putting distance between her days in that minister’s parlor and her new life as a free woman.

Researching family history means relying on ledgers, deeds, census records and government documents. You show these sources in the act of creation, pausing to investigate their flaws. What do you recommend to those facing the same gaps or silences in the historical record?

The Trouble of Color is a story about how we become families, as well the stories we tell about being a family. Each generation had its stories, and they changed over time. I came to see how family letters, interviews, legends and even photographs were more than facts; they were themselves stories. With this, I could see how others wrote down stories about us: on birth and death certificates, census returns, on deed ledgers, and even in history books. These, too, were more than facts.

What I’d say to other researchers is this: Don’t take what you discover at face value, even on an official-looking form. Instead, dig for what is underneath the words on a page: the who, where and why of how those words got written down. There you will find the rest of your story.

Silences nearly stopped me from writing in some moments. And then I learned how to let myself imagine what might have happened. How, for example, had my great-grandmother Mary Jane Holley Jones, nicknamed Jennie, come to think that she, though born enslaved, was the granddaughter of New York real estate magnate John Jacob Astor? She told that story about herself many times, and it was all I had to go on. I first filled the silence with my own imagination, working up a hypothesis or two. Then, I returned to the archives with an openness to finding clues that might let me connect the dots.

When I finally wrote Jennie’s story, I let readers know that I was inviting them into my imagination and then shared what I’d found. You’ll have to decide for yourself about my retelling of Jennie’s life, one that doesn’t rely only on a paper trail.

In The Trouble of Color, your family perseveres through intense personal and political struggles. How did you learn to listen for joy in the archive?

I didn’t start out looking for joy in this story. After all, the book is called The Trouble of Color, and trouble here refers to the difficulties of our family past. But trouble, I learned, has a second meaning, and so this book is also about hope. It opens with the spiritual “Wade in the Water”:

Wade in the water,

Wade in the water, children,

Wade in the water.

God’s gonna trouble the water.

To “trouble,” in this sense, comes from the biblical Book of John: “For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water. Whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had.” To “trouble” here is to heal. It is to be made well.

The lesson is that to be whole, we must also “wade in.” We must risk the currents, the tides, the waves. Perhaps we are not even certain to be strong enough swimmers. Still, we wet ourselves—toes, then feet, knees before thighs. Some days we dive right in. We may fear trouble—the trouble that color can invite into our lives. But what awaits us is the trouble, the trouble that heals us, the trouble that gives us hope. In that, I have found joy.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.