Let’s get this out of the way—any scientist studying Uranus will tell you that they’re tired of the planet being the butt of your jokes.

“I’ve heard them all. I know them all,” says Heidi Hammel, a planetary astronomer at the nonprofit Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. In her experience, the gluteal reference in Uranus’ name makes it hard for her and others to have their work taken seriously outside the scientific community.

That’s too bad, because Uranus is a dynamic planet worthy of attention. Uranus belongs to the class of planets called ice giants; these worlds have thick, gassy shells and innards that are made up of icy material squeezed beyond recognition. Even among its kind, Uranus is a strange planet, given its tilted configuration, its flagging internal heat and its squishable magnetic shield. To date, only one spacecraft, Voyager 2, has dropped by Uranus, and it was only able to examine the world up close for 5.5 hours as it flew past in 1986. In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine declared a dedicated orbiter to Uranus to be a top scientific priority for the next decade.

Even before such a mission gets off the ground, scientists are busy studying the planet by revisiting the trove of Voyager 2 data and examining new Uranian observations from Earth-based telescopes. Nearly 40 years later, new findings are still emerging, rewriting what we know of Uranus. Even so, these discoveries are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding the inner workings of the seventh planet. Here are the top discoveries that scientists have made of Uranus so far.

Uranus is a planet knocked sideways

Two Hubble telescope images of Uranus that were taken one year apart shows that Uranus is constantly remaking its face. The images, snapped in 2005 and 2006, show the rings fading away from view and new cloud patterns—including a dark storm—shifting into existence. NASA, ESA, Mark Showalter (SETI Institute), Lawrence A. Sromovsky (UW-Madison), Patrick M. Fry (UW-Madison), Heidi Hammel (SSI), Kathy Rages (SETI Institute)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/4e/014e67bb-2daf-45e7-a899-1f9d41190773/1_stsci-01evsttcm15br8hcdpzw4dzxmk_web.jpg)

Like Humpty Dumpty, once upon a time Uranus had a great fall. It never got back up again, as far as scientists can tell—the planet’s defining feature is its rotational tilt of 98 degrees. That means, for a quarter of its orbital period, one of its geographic poles faces the sun’s glare head-on, while the shadowed hemisphere faces a 21-Earth-year-long winter. Moreover, Uranus rotates clockwise, in the opposite direction of all of the other planets in our solar system except for Venus.

Theories abound for what tipped Uranus on its side. It may have been a result of a giant impact by an Earth-sized asteroid. Another study proposed that Uranus once had a large moon that tugged on the home planet until it wobbled too far out of its upright position. This wayward moon, at least the size of Uranus’ current largest moon, Titania, also didn’t escape from this gravitational assault it instigated. Scientists think it may have eventually crashed into the planet, thereby freezing Uranus’ recumbent pose.

Uranus has a bizarre magnetic field

Like its spin axis, Uranus’ magnetic field axis is also far from conventional. Whereas the magnetic and geographic poles of most planets usually lie not too far off from each other, Uranus’ magnetic axis slants 59 degrees off the geometric axis and is off-center. Moreover, instead of having a typical dipolar field, the ice giants have chaotic magnetic structures that elude a neat description. Like Neptune, Uranus gets its magnetism from not only the molten core but also hot superionic water ice swirling in the upper mantle, to disruptive effect. The result of these interfering fields is an overall magnetosphere that’s asymmetric and messy.

If a magnetosphere does its job well, it shields a planet from gouging by the sun. But Uranus’ magnetosphere changes drastically with the intensity of the solar wind. During intense solar flares, Uranus’ magnetosphere can be squashed flat, allowing any ions in the atmosphere to escape. In fact, Voyager 2 had found Uranus at a bad time—the solar wind was around 20 times more intense than usual, and it misled researchers to think that Uranus’ atmosphere is typically empty. What a normal day looks like for the Uranian magnetosphere is anyone’s guess. “We caught it at not its average state but probably when it was at its most dynamic, and weird things were happening,” says Jamie Jasinski, a physicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and one of the scientists who made the discovery. “Solar wind is probably a lot more important for Uranus than maybe we first thought.”

The atmosphere is cloudy, breezy—and possibly stinky

In 2012, the Keck II telescope in Hawaii captured images of Uranus’ atmosphere in infrared wavelengths. The planet’s skies feature striated clouds, its North Pole is dotted with a swarm of storms, and a scalloped meteorological ring encircles the globe. Lawrence Sromovsky, Pat Fry, Heidi Hammel, Imke de Pater / University of Wisconsin-Madison/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/19/1b/191b6cb9-2b41-4857-8658-ae03f70e1816/3_uranusindetail-1_web.jpg)

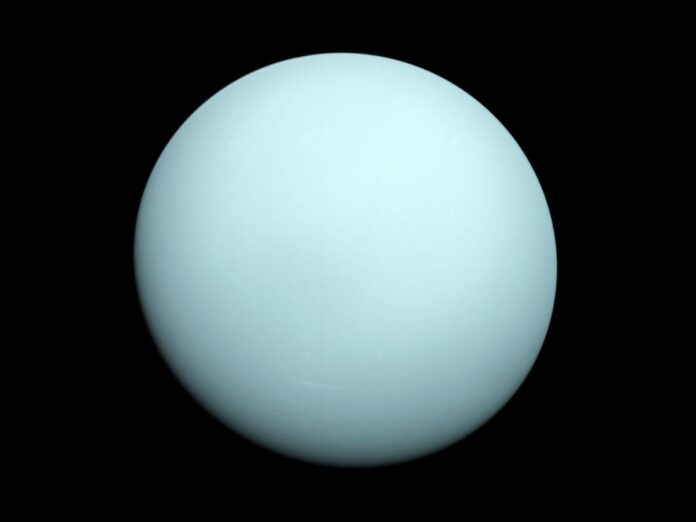

Uranus’ coat might look like a pasty blue wash, but more is going on underneath that pale exterior.

When Voyager 2 passed by, it saw nothing but empty skies. From the images, scientists could make out at most ten faint clouds on the entire planet, leading to widespread belief that Uranus was a placid world. “One of my ancient astronomy books says, ‘The atmosphere of Uranus is bland and uninteresting.’ That was just a fluke,” Hammel says.

Years later, Earth-based telescopes shed new light on Uranus’ atmosphere, giving the scientific community good cause to revise its opinion. For one, scientists have confirmed dozens of clouds coming and going on Uranus’ ever-changing face. For a time, a dark spot similar to Neptune’s graced Uranus’ skies, surrounded by glinting methane ice clouds. The blemish—likely a furious vortex—lasted for less than a year, and another one has never been observed.

Visible or not, fearsome storms brew in the planet’s gaseous sheath. Since the flyby, scientists have detected multiple tempests in infrared wavelengths with the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. Wind speeds zip as fast as 560 miles per hour. A photochemical smog also develops on the planet, and it is thickest where the sunlight is most intense. This occurs at the geographic poles when they point directly at the sun. At the height of summer, the haze is thick enough to crown the polar caps in white.

Uranus’ atmosphere is predominantly hydrogen and helium, but it’s also enriched with methane, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide. The methane on Uranus forms a thick haze and absorbs red wavelengths of light, giving Uranus its signature cyan appearance. Hydrogen sulfide likely causes Uranus’ air to smell of rotten eggs.

Uranus runs colder than all other planets

As Voyager 2 departed Uranus on January 25, 1986, it took one last view of its host and captured this photo. NASA / JPL/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/af/17af5fc1-0df6-4ff9-9f7c-391badd5aab4/4_uranus_final_image_web.jpg)

From ground-based infrared measurements and follow-up assessments with Voyager 2, scientists made a chilly discovery: Uranus sits at a frigid minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit on average, colder than any other planet in the solar system. Temperature wise, the planet is about as chilly as Neptune, even though Neptune is one billion miles further out from the sun compared to Uranus. Usually, the girthier the planet, the slower it cools off from its days of creation. But Uranus, being the third-largest planet in the solar system, is an oddball. Compared with the rest of its planetary siblings, it’s the only member that emits virtually no inner heat—all its meteorological processes on the surface are powered by sunlight.

Scientists can’t say for sure why Uranus runs cold. Perhaps the planet lost all its primordial heat when it received a hard knock. Or, heat is still lurking in the core, but the planet’s outer layers do a superb job at locking it from the outside world. In this case, clouds layers would probably be at fault for Uranus’ stone-cold temperatures, because they likely cocoon the inner heat of the planet like layers of blankets. Recent calculations have shown that it’s possible that methane and water in Uranus’ atmosphere may be trapping the heat at depth. These heavy molecules shut down convection on Uranus, preventing the churning of gases, and thus heat, from deep within the planet to the outer atmosphere.

Icy—and potentially watery—moons populate Uranus’ orbit

A montage of some of Uranus’ moons, from left to right: Puck, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon NASA/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e4/9d/e49d3003-2ccd-461f-a51b-7ebb94ee683e/5_uranus_moons_web.jpg)

Uranus boasts a menagerie of moons. Among its 28 known satellites, the five largest were discovered from ground telescopes before Voyager 2 skimmed past the Uranian system, each of them bearing irregular characteristics that draw much intrigue.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers confirmed the presence of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide ice on the fourth-largest moon, Ariel. These compounds clue researchers in on the presence of carbonate salts that only form in the presence of liquid water. The smallest of the five largest moons, Miranda, stands out for its bizarre appearance. With a violently scuffed surface replete with rifts and steep cliffs and missing chunks, it looks like a much-loved chew toy. Scientists think that perhaps Miranda experienced a cataclysmic impact that tore the world apart, then was hastily put back together. “Clearly something weird is going on with Miranda,” Gao says. “It’s the only one that looks so extreme.”

Modeling studies predict another surprise: Uranus’ quintuplet satellites may harbor underground oceans. At first, scientists thought only the four largest moons had enough heft to interact gravitationally with their parent planet to experience tidal heating in the interior. Now, new computer results published last November suggest that Miranda, too, could also join the ranks of its watery siblings. Their subsurface liquid water is likely mixed with salts, which act as an antifreeze.

Scientists can’t confirm whether these moons have oceans without direct evidence. But just because the planet’s members are tiny and far from the sun doesn’t necessarily mean they’re dead worlds that should be written off from scientific exploration.

Uranus is yet another ringed planet

Uranus in all its haloed glory, captured with the James Webb Space Telescope’s near-infrared cameras. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/53/51/5351c81d-d063-48c5-8d36-0871270fedba/6_stsci-01gwqdq0hgy8v0baeknw5zxpxp_web.jpg)

Thirteen rings pirouette around Uranus. Unlike Saturn’s sweeping skirt, Uranus’ wreath is tightly confined into dense and narrow arcs. Why they’re kept on a tight leash is an ongoing mystery. One suggestion is that the rings are forming from the dissolution of icy moons then clumping back into new bodies—Miranda’s beaten-up facade is certainly a point in favor of this idea.

Moreover, scientists are flummoxed by the chemical makeup of the shards that make up the rings, given that they’re unusually dark. In fact, they’re the darkest material in the solar system. Scientists think that the ice particles are composed of water material mixed with organics, or they’re blocks of methane ice singed black. Against Uranus’ bright exterior, the rings are difficult to discern except with infrared telescopes.

Images by the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes revealed that the rings come colorfully striped. The inner rings are a dustier and red, while the outer rings lean toward blue, like Saturn’s water-rich halos. The Saturnian circlet is nourished by the watery plumes of one of its moons, leading scientists to wonder whether a similar hydration mechanism is at play on the outer bands of Uranus rings. For that, researchers cast their suspicions on the tiny speck of a moon, Mab, lying just within the edge of Uranus’ belt. Mab is too small to spout plumes on its own, so researchers hazard that asteroid bombardment kicks off icy detritus from the moon and shoots it into circulation around Uranus. “Where’s the blue coming from?” says Hammel, a co-author on the study on Uranus’ colorful rings. “That’s another mystery that is not solved.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kim.png)