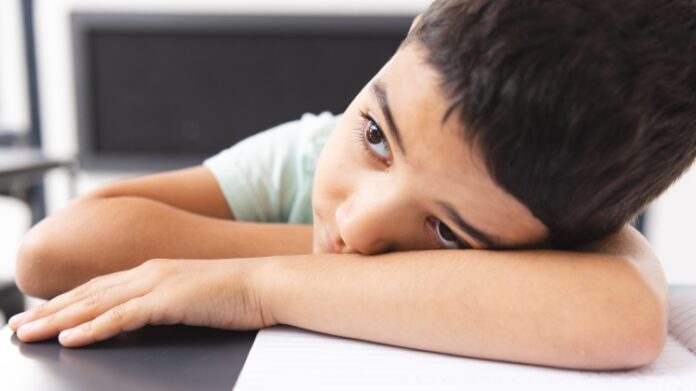

Shenila Khoja-Moolji‘s The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood considers the ways in which Muslim boys face gendered and racialised discrimination in the US and India, including in school settings. Drawing on interviews with Muslim boys in Queens, New York, Khoja-Moolji’s thought-provoking book reveals how these youths are profiled and stigmatised for political and capitalist gain, writes Saadia Ahmed.

The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood. Shenila Khoja-Moolji. University of Minnesota Press. 2024.

Shenila Khoja-Moolji, the author of Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan (2021) and Forging the Ideal Educated Girl (2018) is one of the most prominent scholars in the areas of gender, Muslims, and Pakistan Studies. As a PhD scholar researching the area of the performativity and reinforcement of gender relations in Pakistan, I came across Khoja-Moolji’s work while researching the construction of the “ideal” Muslim girl narrative in the Indian sub-continent. Fascinated by the author’s clarity of thought resolve to bring the less-discussed aspects of gender relations in post-colonial Pakistan, I was eager to read The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood, Khoja-Moolji’s latest book, The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood, exploring the construction of stereotypes around Muslim boyhood in the US and India. This impressive book grapples with the seemingly missing or ignored link between the politics of fear and capitalist profits in both countries and challenges the hegemony of stereotypes perpetuated by Islamophobia.

Shenila Khoja-Moolji, the author of Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan (2021) and Forging the Ideal Educated Girl (2018) is one of the most prominent scholars in the areas of gender, Muslims, and Pakistan Studies. As a PhD scholar researching the area of the performativity and reinforcement of gender relations in Pakistan, I came across Khoja-Moolji’s work while researching the construction of the “ideal” Muslim girl narrative in the Indian sub-continent. Fascinated by the author’s clarity of thought resolve to bring the less-discussed aspects of gender relations in post-colonial Pakistan, I was eager to read The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood, Khoja-Moolji’s latest book, The Impossibility of Muslim Boyhood, exploring the construction of stereotypes around Muslim boyhood in the US and India. This impressive book grapples with the seemingly missing or ignored link between the politics of fear and capitalist profits in both countries and challenges the hegemony of stereotypes perpetuated by Islamophobia.

Khoja-Mooolji draws an important analogy between the proto-terrorist stereotype associated with Muslim boys and the practices of racialisation.

The Impossibility of the Muslim Boyhood begins with the examples of two boys arrested in the US on account of the pro-terrorist narrative associated with young Muslim male children. In January 2017, a five-year-old Muslim boy was hand-cuffed at Washington Dulles Airport while in 2015, a fourteen-year-old Muslim boy Ahmed Mohamed was handcuffed and held in a detention centre for bringing a home-made digital clock to the school which his English teacher assumed to be a time bomb (60). The first question that arises in the mind of any person free of bias is why a child would be handcuffed on account of a “perceived” crime. Khoja-Mooolji draws an important analogy between the proto-terrorist stereotype associated with Muslim boys and the practices of racialisation. The discrimination against Muslim boys as a potential threat who would grow up to become terrorists is similar to racism where the outgroup is considered “less pure” and hence less worthy of the basic affordances of human rights that would be made available to the dominant group. The surveillance and othering in schools play an important role in the construction and reinforcement of the proto-terrorist narrative.

What purpose does such a narrative serve? Khoja-Moolji identifies how the marginalisation and othering of Muslim boys benefit the capitalist regimes. On one hand, these create a state of fear among the masses thereby justifying the wars waged against Muslim countries. On the other hand, when the same Ahmed Mohamed who is handcuffed and held in a detention centre because for what his English teacher assumed to be a time bomb is invited to the White House, it builds an air of credibility and good will for the politicians and policymakers who can now flaunt their contribution to diversion and inclusivity.

Muslim women [are presented] as helpless creatures with no agency who need to be saved by their “well-wishers” in the West who are ever willing to wage war against the Muslim countries (read: legitimising the weapons industry that thrives on the anxieties of threat and fear).

The book is based on the narrative analysis of interviews with 26 non-white Muslim boys conducted in Queens, New York between April and June 2017 in the in the aftermath of the Dulles Airport arrest. Khoja-Moolji addresses her research participants by their first names in a conscious attempt to humanise them and acknowledge how young they are. Theyshared many incidents where they or other Muslim boys they knew were treated as proto-terrorists by the figures of authorities and children in their schools. For instance, In 2016, a six-year-old Muslim boy Abdul Aziz was kicked in his school bus aisle because he was a Pakistani Muslim; his older brothers have been called terrorists in the past. A key theme that emerges within these conversations is that this discrimination is not only religious but also gendered. For instance, some research participants insisted that Muslim girls were dealt with more softly and politely as compared to boys. To them, if the homemade digital clock belonged to a girl, the teacher would have interrogated and probed the matter instead of getting her handcuffed like Ahmed Mohamed (50). Muslim boys are treated as potential terrorists who are likely to turn violent at any age. Resultantly, they are denied the affordances of innocence and boyhood and hence the title “The Impossibility of the Muslim Boyhood” by the author.

Here it is crucial to note that this assumption about the Muslim boys can be linked to the portrayal of Muslim men as sexually frustrated and violent by the Western media and literature (44). Abu-Lughod in her 2013 book Do Muslim Women Need Saving? has highlighted the same stereotype about Muslim men depicted in the Western media as uncouth and feral and prone to commit hate crimes against non-Muslim men as much as the Muslim women from their own community. This, in turn, essentialises and homogenises the Islamic cultures around the world as an umbrella term and also presents Muslim women as helpless creatures with no agency who need to be saved by their “well-wishers” in the West who are ever willing to wage war against the Muslim countries (read: legitimising the weapons industry that thrives on the anxieties of threat and fear).

While we have a heated debate against the misogyny and gender-based hate crimes incited against women by Muslim men, it is important to acknowledge and remember that racialisation cannot be essentialised. When Kelly Oliver wonders why the American soldiers committing sexual violence against the prisoners in Abu Ghraib are excused for being ignorant and innocent, one needs to view the discounted affordances of innocence and empathy offered to those coming from the dominant White race. Academia, though mostly criticised for being estranged from the “real” issues, is known for its theoretical contribution to activism and social justice. While Khoja-Moolji explores Muslim boyhood and the associated practices of hate and anxiety working against Muslim male children, she also directs global audiences’ attention toward standing up to the proliferation of hate and divide against any race, gender, or class. The methodology based on the narrative analysis of the lived experiences of Muslim boys in the US adds to the credibility of this research, making it a must-read for anyone interested in exploring gender politics and racism.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image: wavebreakmedia on Shutterstock.

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe to our newsletter for a round-up of the latest reviews sent straight to your inbox every other Tuesday.