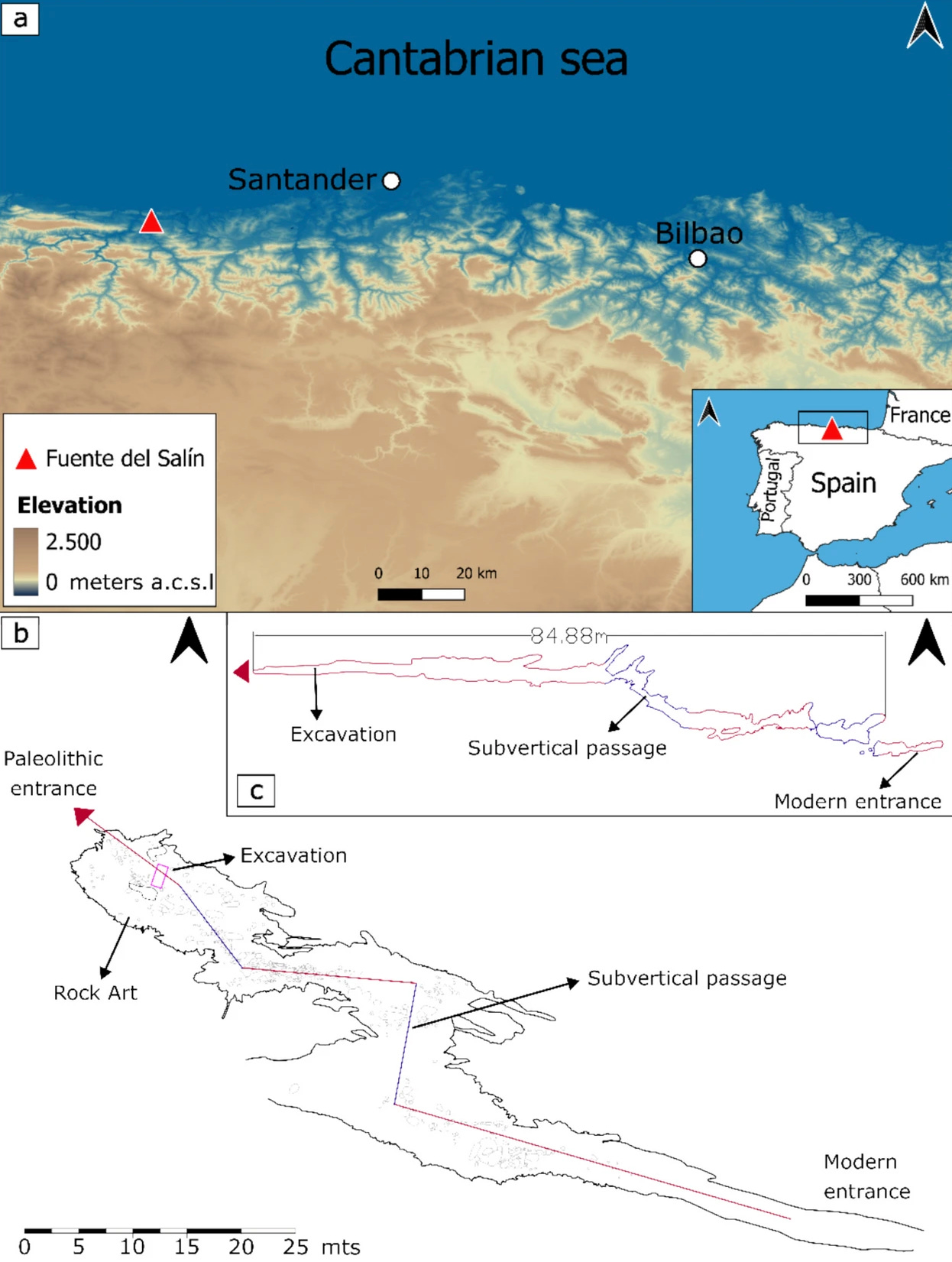

Fire has long been a cornerstone of human existence, providing warmth, protection, and a means to cook food. But was its use during the Upper Paleolithic purely practical, or did it hold deeper cultural significance? A new study from the Fuente del Salín cave in Cantabria, Spain, seeks to answer this question by examining the role of fire in Gravettian hunter-gatherer life. The research, published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, presents compelling micro-archaeological evidence that fire was not just a survival tool but a defining cultural trait of the Gravettian tradition.

Through detailed analysis using micromorphology, micro-X-ray fluorescence (µ-XRF), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM-EDX), the researchers reconstructed the use of fire at the site. Their findings challenge the assumption that intensive fire use was simply an adaptation to periglacial conditions in central and eastern Europe, instead suggesting that it was an integral part of Gravettian identity across the continent.

“The intensive burning, systematic reuse of combustion features, and multiple purposes of the fires at Fuente del Salín are comparable with Gravettian sites from central and eastern Europe, indicating that these fire-use behaviors probably do not reflect a regional adaptation to periglacial environments but a cultural trait of the Gravettian tradition across Europe.”

For years, archaeologists have debated whether fire use among Paleolithic hunter-gatherers was primarily dictated by environmental necessity or if it was a deeply ingrained social practice. The Gravettian period, which lasted from roughly 33,000 to 22,000 years ago, saw some of the coldest climates of the Ice Age, particularly in regions like the Middle Danube Basin. Sites such as Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic and Grub-Kranawetberg in Austria have revealed extensive evidence of fire use, leading some researchers to conclude that it was a response to extreme climatic conditions.

However, Fuente del Salín offers a different perspective. Unlike central and eastern Europe, Cantabria did not experience the same periglacial conditions. Yet, the evidence from the cave suggests that Gravettian foragers used fire in strikingly similar ways. The presence of stacked hearths, burnt bones, charred organic material, and layers of ashes indicates a systematic approach to fire maintenance and reuse. These patterns suggest that fire was more than just a means to combat the cold—it was part of a broader social and cultural practice.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study is the discovery of burnt grass beddings. In other Upper Paleolithic sites, such as Sibudu Cave in South Africa, similar layers of burnt vegetation have been interpreted as evidence of deliberate sanitation practices. Burning old bedding could have helped control parasites, a behavior still observed in some modern hunter-gatherer societies. The presence of these features at Fuente del Salín suggests that Gravettian groups may have engaged in comparable hygienic practices, reinforcing the idea that fire was not merely a tool but an element of daily life with ritualistic or symbolic importance.

Additionally, the researchers found high concentrations of manganese oxides in the combustion features. Some scholars have speculated that Neanderthals used manganese dioxide to aid in fire-starting, as it reduces the ignition temperature of wood. Could the Gravettian people have inherited this knowledge? If so, it would further emphasize the sophistication of their pyrotechnology.

Beyond its practical applications, fire likely played a critical role in fostering social cohesion among Gravettian groups. Sitting around a fire would have been a time for storytelling, teaching, and reinforcing group identity. The repetitive use of specific hearths suggests that Gravettian sites were not just temporary encampments but places of recurrent gathering and social continuity.

The study’s findings align with other research suggesting that Gravettian populations had relatively low population densities and high mobility, yet maintained strong regional traditions. The standardization of fire use across diverse environments indicates a shared cultural knowledge passed down through generations.

The study at Fuente del Salín contributes to a growing body of evidence that challenges the notion of the Gravettian as simply an adaptive response to Ice Age conditions. Instead, it presents a more nuanced picture of these hunter-gatherers as active cultural agents who manipulated fire for multiple purposes beyond survival.

While fire may have initially been a necessity, it evolved into something more—a medium for social organization, hygiene, and possibly even ritual. The Gravettian mastery of fire provides a glimpse into the complexity of their cultural traditions, reshaping our understanding of how early humans structured their lives.

The Gravettian people were not merely surviving in their environment—they were shaping it. Their use of fire, as evidenced by the Fuente del Salín cave, was systematic, widespread, and deeply ingrained in their culture. This challenges long-held assumptions that early human technologies were purely reactionary adaptations.

Instead, the Gravettian mastery of fire reflects an early example of humans creating intentional cultural traditions, shaping their environments in ways that would influence future generations. As archaeologists continue to unearth more evidence from Paleolithic sites, one thing is clear: fire was not just an element of survival—it was a beacon of human ingenuity.

For those interested in the evolution of fire use and cultural practices among ancient human populations, here are some key studies:

-

Murphree & Aldeias (2022) – Examines how Gravettian populations used a variety of combustion features, including fire installations and baked clay structures. DOI: 10.1007/s12520-024-02126-x

-

Mallol et al. (2017) – Discusses the micromorphological analysis of combustion features in Paleolithic sites. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.04.006

-

Sorensen (2024) – Explores how manganese dioxide was used in fire-starting techniques by early humans. DOI: 10.3989/egeol.44131.593