Neanderthals have long been a mystery. They were our closest relatives, yet they disappeared while we thrived. For decades, scientists have debated whether their extinction was the result of dwindling genetic diversity, climate pressures, or competition with early Homo sapiens. A new study published in Nature Communications adds a surprising twist: the key to understanding Neanderthal population decline may lie in the shape of their inner ear.

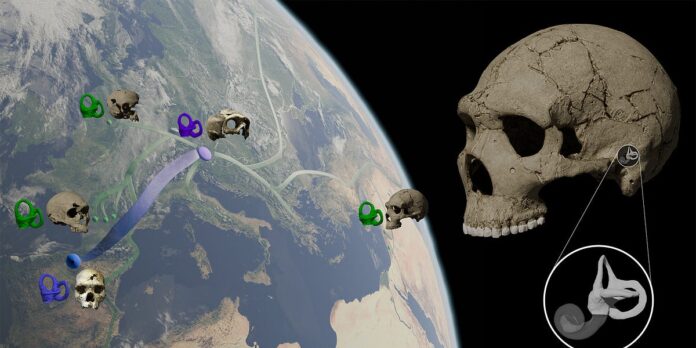

A team of researchers, led by Alessandro Urciuoli of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, turned to the semicircular canals—structures within the bony labyrinth of the inner ear responsible for balance—to test an idea. Could changes in Neanderthal ear morphology reflect a bottleneck event in their evolutionary past? Using a sophisticated geometric morphometric approach, they analyzed the semicircular canals of Neanderthal fossils spanning hundreds of thousands of years. Their findings suggest a sharp decline in morphological diversity that coincides with a long-suspected genetic bottleneck event.

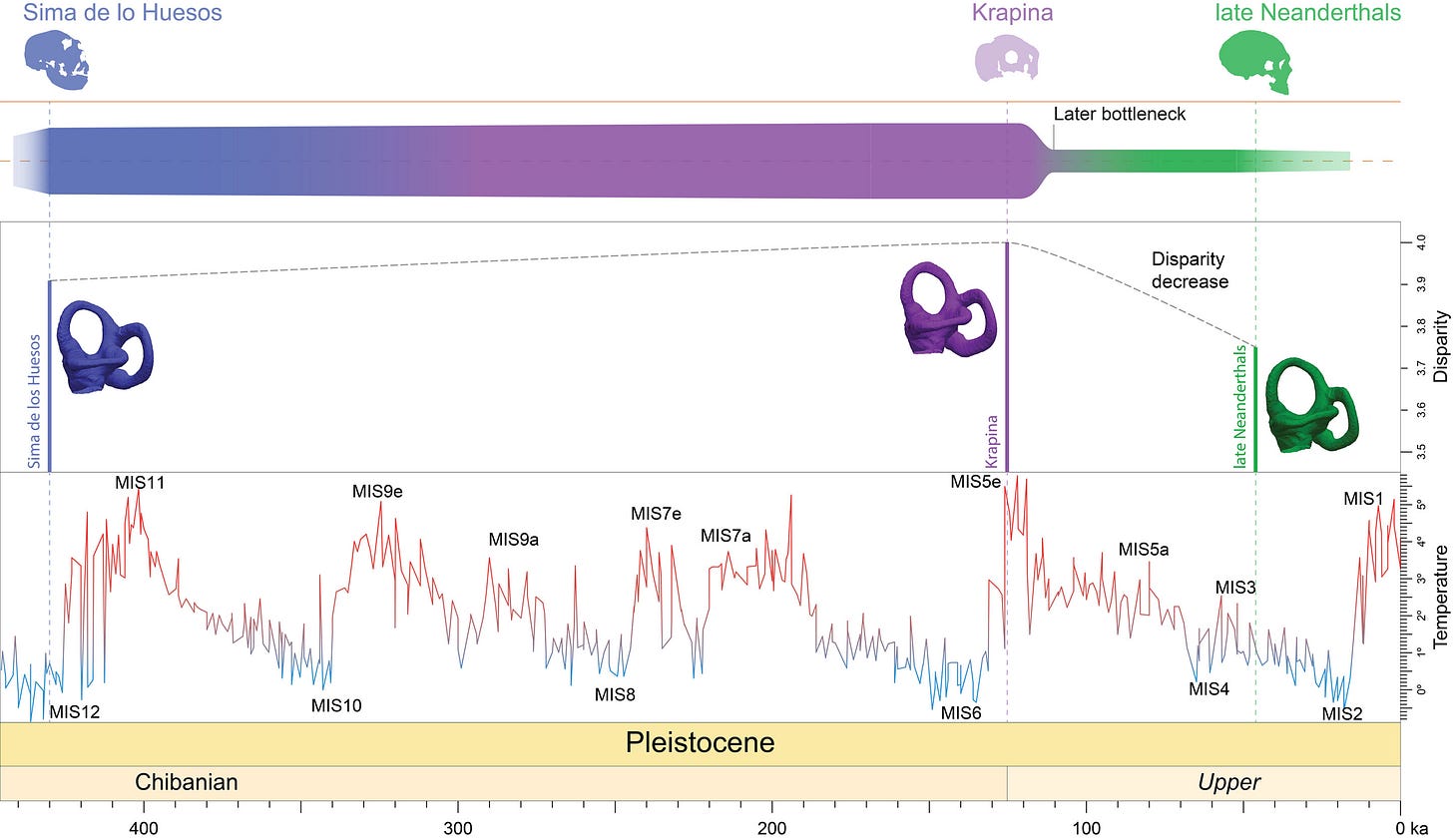

“Our results identify a significant reduction in disparity after the start of Marine Isotope Stage 5, supporting our hypothesis of a late bottleneck, possibly leading to the derived morphology of Late Pleistocene Neanderthals,” the authors state.

This discovery offers a fresh perspective on Neanderthal evolution. Rather than a gradual decline in diversity, the evidence points to a late and abrupt event that may have set the stage for their eventual disappearance.

Neanderthals evolved from Middle Pleistocene populations, often grouped under Homo heidelbergensis, and were established in Eurasia by at least 400,000 years ago. Their genetic divergence from Homo sapiens and Denisovans occurred between 765,000 and 550,000 years ago, based on molecular clock estimates. But as Neanderthals became increasingly distinct, something peculiar happened.

For years, scientists believed that Neanderthals experienced an early genetic bottleneck—a sharp reduction in population size that limited their genetic diversity. However, genetic data from fossils has not confirmed this theory. The new study challenges this assumption by using morphological data as a proxy for genetic variation.

“Greater phenotypic variation should be present before a drastic reduction of genetic variation, such as before a bottleneck event,” the researchers explain.

To test their hypothesis, they examined inner ear morphology from three key Neanderthal populations:

-

Sima de los Huesos (Spain, ~430,000 years ago) – One of the earliest known populations on the Neanderthal lineage.

-

Krapina (Croatia, 130,000–120,000 years ago) – A late Middle Pleistocene group showing clear Neanderthal traits.

-

Late Neanderthals (40,000–64,000 years ago) – Fossils from Western Europe, representing the last phase of Neanderthal existence.

The results were striking. Early Neanderthals at Sima de los Huesos and Krapina exhibited high levels of morphological diversity, suggesting a broad genetic pool. But in later Neanderthals, the variation plummeted—strongly implying a genetic bottleneck.

“The reduction in diversity observed between the Krapina sample and classic Neanderthals is especially striking and clear, providing strong evidence of a bottleneck event,” the study states.

A dramatic loss of genetic diversity often signals a major population crisis. The study suggests that the bottleneck occurred after 130,000 years ago, during a period of significant climate fluctuation. Marine Isotope Stage 5 (MIS 5), which lasted from roughly 130,000 to 80,000 years ago, saw fluctuating temperatures that may have fragmented Neanderthal populations.

The findings align with previous research suggesting that Neanderthals were never a large, stable population. Instead, they lived in relatively isolated groups, with occasional waves of expansion and contraction. The study’s authors speculate that worsening climatic conditions and habitat fragmentation could have led to prolonged periods of low genetic exchange, further intensifying the effects of the bottleneck.

“Drastic climatic changes likely had profound impacts on the genetic and morphological variability of the Neanderthal lineage,” the authors write.

The implications are profound. While earlier studies have suggested that Neanderthals may have interbred with early Homo sapiens as far back as 200,000 years ago, this new evidence raises the possibility that hybridization was not enough to prevent their decline.

The study’s conclusions challenge traditional models of Neanderthal evolution. Previous theories largely fell into two camps:

-

The Accretion Model – Neanderthals evolved gradually through accumulating small genetic changes over time.

-

The Two-Phase Model – Neanderthals underwent two distinct evolutionary phases, with a major shift occurring due to a bottleneck.

The new research suggests that neither model fully explains Neanderthal evolution. Instead, it paints a more complex picture in which early Neanderthals retained high levels of diversity, but something happened later that dramatically reduced their variability.

“Neither accretion nor organismic models are entirely capable of describing the complex processes that shaped the variation observed in Middle and Late Pleistocene Neanderthals,” the study notes.

This raises a key question: if Neanderthals had already experienced a severe genetic bottleneck before the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe, were they already on the path to extinction before we ever encountered them?

One of the most persistent debates in paleoanthropology is what ultimately led to the disappearance of Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago. Some argue that direct competition with Homo sapiens—either for resources or through conflict—was the decisive factor. Others suggest that climate change played a larger role.

This new study complicates that narrative. If Neanderthals had already suffered a dramatic loss of genetic diversity 100,000 years before their final disappearance, it suggests that their downfall may have been a much longer process than previously thought.

“The identification of a phenotypic bottleneck later than 130–120 ka has consequences for our understanding of Neanderthal evolution,” the study concludes.

In other words, Neanderthals may have been struggling long before Homo sapiens arrived in large numbers. The genetic bottleneck may have left them vulnerable to further population declines, inbreeding, and a reduced ability to adapt to environmental changes.

This study provides an important missing piece in the puzzle of Neanderthal extinction. By using inner ear morphology as a proxy for genetic diversity, researchers have identified a major evolutionary bottleneck that likely played a pivotal role in shaping the fate of the Neanderthal lineage.

Rather than viewing Neanderthals as a single, stable population that slowly declined, this research suggests they were part of a highly dynamic and fluctuating metapopulation, prone to cycles of expansion and collapse.

Did this bottleneck seal their fate long before Homo sapiens became a dominant force in Europe? That remains an open question, but one thing is clear: Neanderthal evolution was far more complex than we once thought.

-

Genetic Bottlenecks in Neanderthals and Denisovans (Nature) – DOI: 10.1038/nature18648

-

Climate Change and Neanderthal Extinction (Science) – DOI: 10.1126/science.aay8177

-

Neanderthal Morphological Variation (PLOS ONE) – DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226555