A consortium of companies found a clever way to recycle phone parts, showing how reusing electronics can improve sustainability.

Image courtesy of Deutsche Telekom

Electronic waste is a huge environmental problem of which disposed cell phones are a major contributor. Think about it, all that metal, plastic, and working semiconductors go into landfills. Some materials, such as gold from PCB fingers, can be reclaimed and used in other ways, but what if the working semiconductors could get a second life? That’s what engineers at Deutsche Telekom, Infineon, Fairphone, MaxLinear, Sagemcom and Citronics wondered, so they did something about it. The result: a prototype DSL router that contains 70% reused parts from cell phones and telecom network routers.

Curious as to how the engineers managed to build the router, I spoke with Henning Never from Deutsche Telekom and Julian Haslberger from Infineon.

Why a DSL router?

In addition to being a mobile carrier, Deutsche Telekom is also a fixed-line communications provider. Thus, the company sells its own fixed-line user equipment, including routers. “We try to make our own hardware more sustainable,” said Never. “We started with the packaging, removing single-use plastic. Now, we use cardboard only.”

Not satisfied with simply removing single-use plastic, DT engineers knew that phones, in-home user equipment, and telecom networking equipment would still end up in landfills. They wanted a way to reuse semiconductors, connectors, and other components.

Figure 1. A Fairphone 2 served as the primary parts contributor for the DSL router project. (Image: Fairphone)

To learn more about electronic component reuse, DT engineers contacted companies and institutions, ultimately forming a consortium that includes Dutch smartphone manufacturer Fairphone, semiconductor manufacturer Infineon, and contract manufacturer Citronics — a company with previous experience reusing Fairphone 2 parts. The result: a DSL router made from old cellphone parts.

The proof-of-concept DSL router emerged because, according to Never, it’s “not a very advanced piece of electronics,” said Never. “We are one of the largest suppliers in Europe for routers with the ‘T’ brand logo. That’s why we decided to build a router.” Never noted that many fixed connections in Germany use DSL and very-high-speed DSL (VDSL).

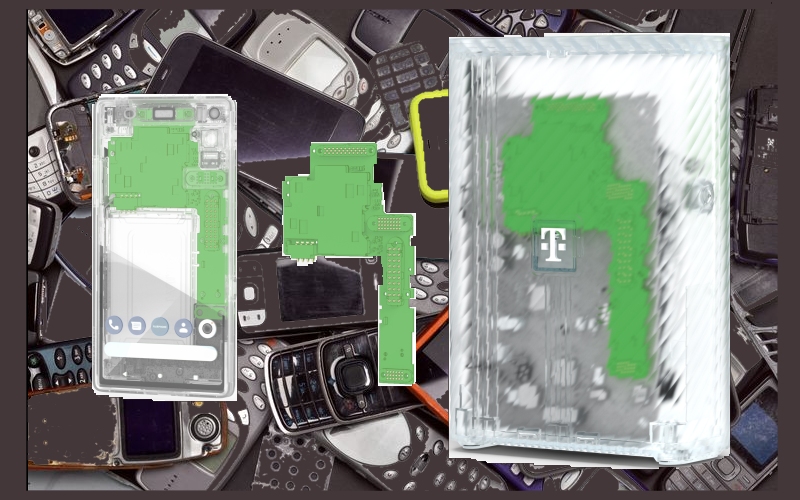

The prototype uses parts from a Fairphone 2 (Figure 1). Parts such as the camera and battery are easily removed and replaced. Fairphone emphasizes reusing and recycling parts and materials. The phone’s modular design (Figure 2) meant that engineers could use the phone’s PCB assemblies, which eliminated having to desolder ICs from the board. They did have to remove some connectors to accommodate the router’s case.

Figure 2. The Fairphone 2’s modular design lets engineers use the phone’s semiconductors without removing them from the PCBs. (Image: Deutsche Telekom)

“That was the reason why we went for the Fairphone 2,” said Never. It’s not a high-performance device compared to what we have today. We had limitations from a technological point of view, and this is the reason why we didn’t try to build a high-end 1 gig optical router. We just wanted to have a proof-of-concept that could perform decent tasks, but it’s not outrageously complex.”

The prototype DSL router operates over an existing copper line. Never noted that many of Germany’s copper lines received an upgrade that moved the active systems — digital subscriber line access multiplexers (DSLAMs) — to distances roughly 250 m to 500 m from the user to the central office. The shorter copper lines resulted in speed increases, which enabled the use of VDSL with speeds up to 250 Mb/sec. The price: more network equipment that runs hotter than previous equipment. That required new cooling techniques.

Reused parts

Engineers reused the phone’s main board, which contains the CPU and memory. They added a USB port to connect the router to a host computer for firmware downloads and diagnostics. They then added connectors from an old telephone router to physically attach the unit to the network. A DSL modem IC from an old router connects the prototype router’s signals to the network. The prototype’s internal firmware is based on Linux.

Because the phone already had Wi-Fi capabilities, engineers connected it to user equipment. The router uses just one antenna as opposed to four or six, as modern routers use. Because the parts came from a cellphone, the router can connect to the cellular 4G network. Never noted that while the router has cellular connectivity, engineers have not tested it in this prototype.

Home routers that provide wired internet access usually have Ethernet ports. In this project, engineers used an Ethernet interface chip (VDSL chip) from a ten-year-old DSL modem that connects to the Fairphone mainboard. “Our initial idea was to desolder and reuse a VDSL chip from an old Deutsche Telekom branded router, but then we learned that the chip was designed to work only with the corresponding CPU. That would have eliminated the Fairphone CPU from the project. “The understanding that using old electronics is not just about getting the hardware right but that we also need to solve the problem of proprietary chipset designs,” said Never. “That was an important lesson for us.”

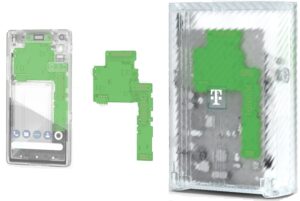

While much of the prototype incorporated reused components, engineers had to design a new board to connect the phone’s boards to the network interface IC, the USB IC and mount connectors to connect to the network and provide power through an external power adapter. Figure 3 shows the evolution from a smartphone to a prototype DSL router.

Figure 3. Engineers designed a board to hold the boards from the phone and marry them with components reclaimed from a telecom network router. The final prototype appears on the right. Image courtesy of Deutsche Telekom.

“The beauty of the Fairphone comes from its modular design,” added Haslberger. “You can disassemble it and reuse the parts. When you go down to the semiconductor level, that’s where Infineon and other players came in.”

Infineon and other project partners contributed used components such as connectors and the DSL modem IC. Engineers disassembled or desoldered the used parts, then reconditioned and tested them as part of the normal test procedure before installing them into the prototype. Their goal was to demonstrate the levels at which it makes sense to reuse electronics and to think through possible scalable future projects.

“We also needed some transistors and capacitors,” added Never. We took them from the old telecom router.” Engineers also needed two microcontrollers to control the Fairphone and the VDSL board interplay. Those were also reused.

Beyond the prototype

To scale the project to production status, engineers will need to create an ecosystem because the process for this first unit was labor intensive, noted Haslberger. “We have to explore the whole value chain to see if it’s feasible. That’s what we’re aiming for in this project.” Automating the reuse process, from disassembling the phone to removing and testing parts, is key to making it successful.

The DSL router built from reused parts was displayed at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona. After MWC, engineers plan to design a board so that parts prone to upgrades can be easily installed as technology advances. For example, they want a way to use today’s and future Wi-Fi radios to increase bandwidth.

Building a router or other device from cellphone parts certainly seems like a good way to reuse parts and improve sustainability. Phones have become part of the ecosystem because Deutsche Telekom buys back phones when customers upgrade, so there should be a constant supply.

“We have plans to build more,” said Never.