Long before the great empires of Babylon and Assyria rose to power, an ancient civilization in southern Mesopotamia was already mastering the art of water management. New research published in Antiquity by geoarchaeologist Jaafar Jotheri and his team reveals a massive, intricate irrigation system in the Eridu region—one that predates the first millennium BCE. This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about early farming societies and highlights the ingenuity of ancient Mesopotamian farmers who tamed the unpredictable waters of the Euphrates.

For centuries, our understanding of early irrigation in Mesopotamia has relied largely on indirect evidence, such as cuneiform texts and archaeological remains of later canal networks. But in the Eridu region, a unique environmental twist has preserved an ancient agricultural landscape almost untouched for millennia. A shift in the Euphrates’ course in the early first millennium BCE left the region dry and uninhabited, effectively freezing its irrigation system in time.

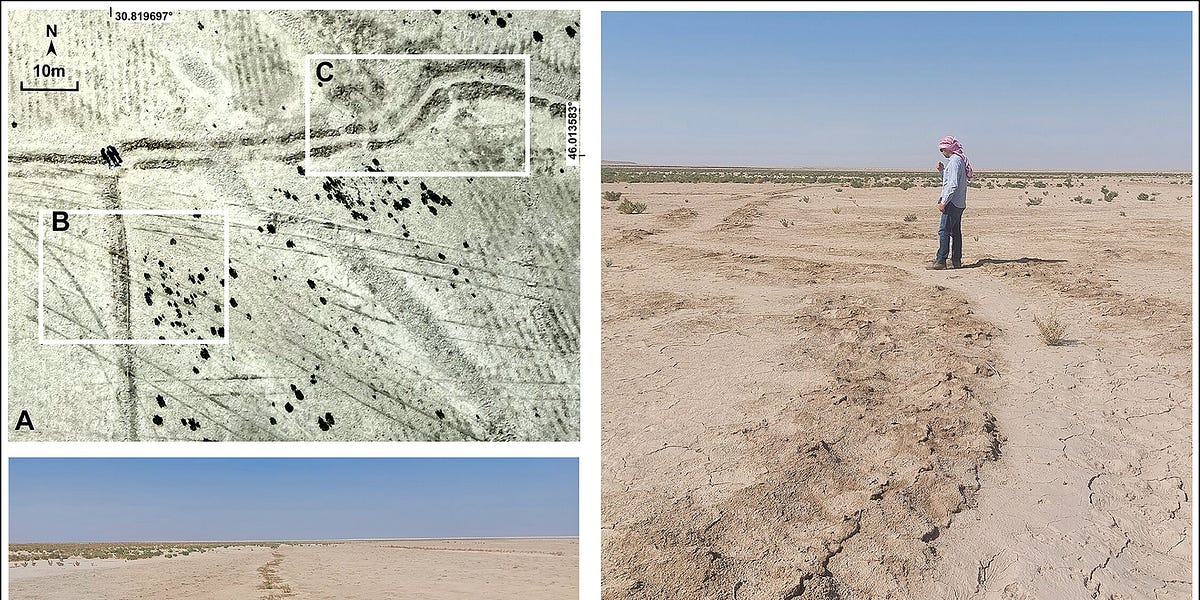

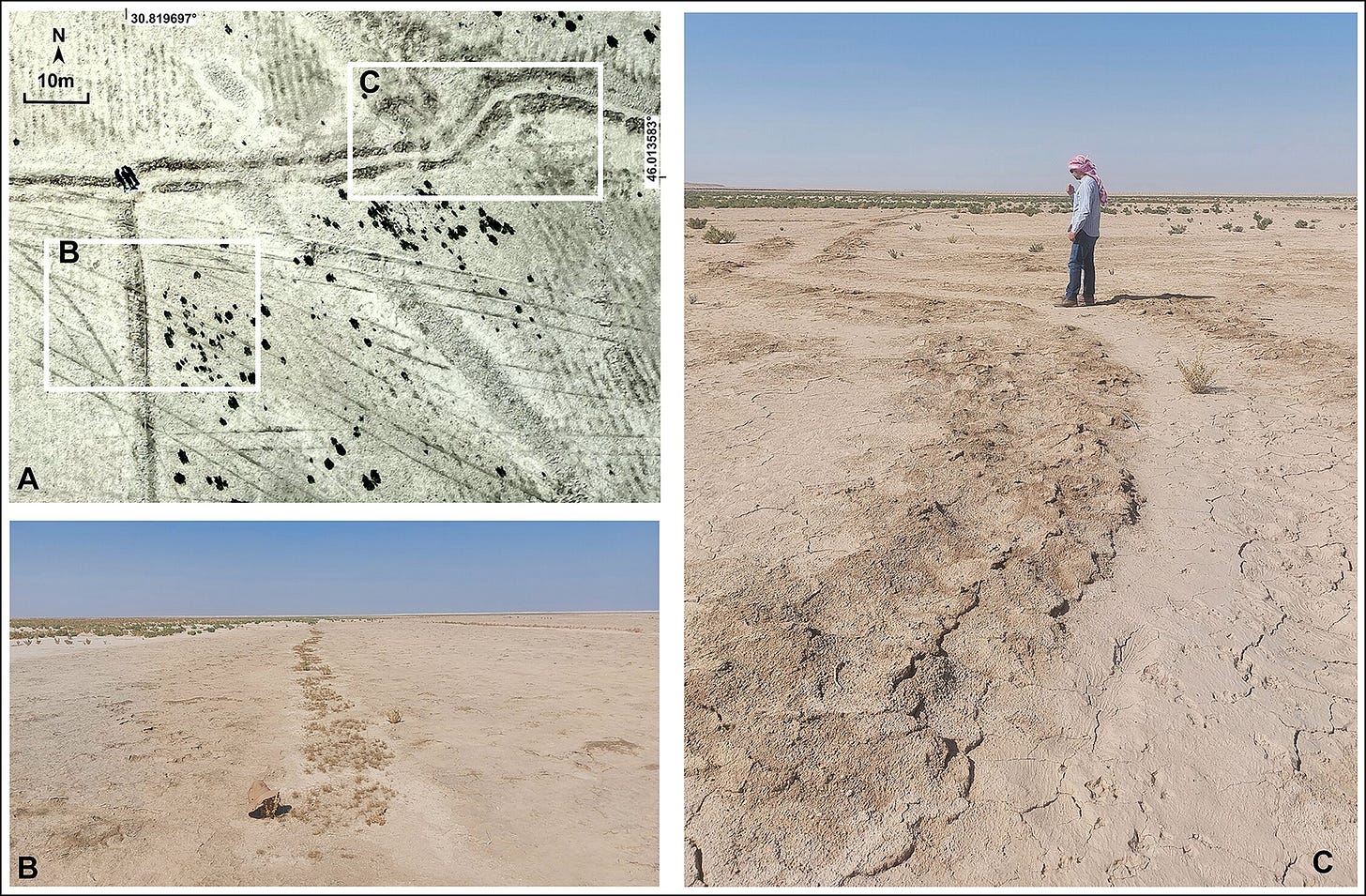

Using a combination of satellite imagery, drone photography, and field surveys, the researchers mapped an astonishing 200 primary irrigation canals, some stretching up to 9 kilometers long and 5 meters wide. These primary canals linked directly to the Euphrates, channeling water to more than 4,000 secondary canals, which in turn irrigated over 700 ancient farms. The level of planning and engineering on display suggests a highly organized society that understood how to manipulate its environment for sustained agriculture.

“The Eridu region was occupied from the Early Ubaid to the Neo-Babylonian periods,”

the researchers note, pointing out that this means irrigation techniques evolved over thousands of years. The sophistication of the canal network reflects not just survival but adaptation, as generations of farmers adjusted their methods to shifting landscapes and changing climates.

Most of what we know about Mesopotamian irrigation comes from the Parthian and Sasanian periods, roughly a thousand years after the newly discovered Eridu canals were in use. This raises a compelling question: Did the knowledge of these older irrigation systems influence later civilizations, or was this an isolated agricultural phenomenon?

“Little is known about earlier irrigation canals,”

the study notes, pointing to the fact that younger networks often covered or replaced older ones. The Eridu system, however, appears to have remained remarkably intact due to the natural shift in the river’s course. This is a rare case where nature has preserved a vital piece of human history.

The study highlights two key natural features that made this irrigation system possible. First, the elevated levees of the Euphrates allowed farmers to use gravity to distribute water across their fields. Second, the presence of crevasse splays—natural breaks in the riverbanks—helped disperse water more efficiently across the floodplain. These natural features were not simply exploited but actively modified by ancient engineers, who dug artificial canals over the crevasse splays to extend the reach of their irrigation system.

The scale of the canal network suggests a coordinated effort requiring immense labor and expertise. It’s likely that irrigation was not just an individual or family enterprise but a communal effort, managed at a regional level. This level of organization points to a sophisticated society with knowledge-sharing networks that ensured the sustainability of its agricultural practices.

One of the most pressing questions raised by this discovery is when exactly each canal was in use. The research team acknowledges that dating these canals more precisely is crucial to understanding the evolution of irrigation in Mesopotamia.

“Canals require immense labor and experience in water management to operate successfully,”

the authors note, emphasizing the need for future research to determine how these systems changed over time. If archaeologists can link these canals to specific historical periods through radiocarbon dating or sediment analysis, we may be able to trace the origins of large-scale irrigation in the ancient world.

Furthermore, the study suggests comparing the physical remains of the canals with descriptions in ancient Mesopotamian texts. Cuneiform records provide detailed accounts of agricultural management, taxation, and irrigation laws. If researchers can match specific canals to textual references, it would provide an unprecedented look at how these systems were governed.

This discovery underscores the critical role water played in shaping early Mesopotamian societies. While the region is often called the “Cradle of Civilization,” this phrase typically conjures images of ziggurats, cuneiform tablets, and city-states. But before any of that was possible, there was water—harnessed, redirected, and controlled through the ingenuity of early engineers.

Jotheri and his team have opened a new window into one of the earliest and most advanced irrigation networks ever found. This is not just a discovery about canals—it’s a story about resilience, adaptation, and the enduring human quest to master the natural world.

For those interested in further reading, similar studies have explored the evolution of irrigation and water management in ancient Mesopotamia:

-

Wilkinson, T.J., Rayne, L., & Jotheri, J. (2015). Hydraulic landscapes in Mesopotamia: The role of human niche construction. Water History, 7, 397–418. DOI: 10.1007/s12685-015-0127-9

-

Jotheri, J. & Allen, M.B. (2020). Recognition of ancient channels and archaeological sites in the Mesopotamian floodplain using satellite imagery. New Agendas in Remote Sensing and Landscape Archaeology in the Near East, 283–305. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.19

-

Lang, D. & Ertsen, M.W. (2024). Modeling southern Mesopotamia’s irrigated landscapes. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 31, 1062–101. DOI: 10.1007/s10816-023-09632-7