:focal(640x427:641x428)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/50/2a50d181-b75d-4682-9870-011110214939/mouse_brain.jpg)

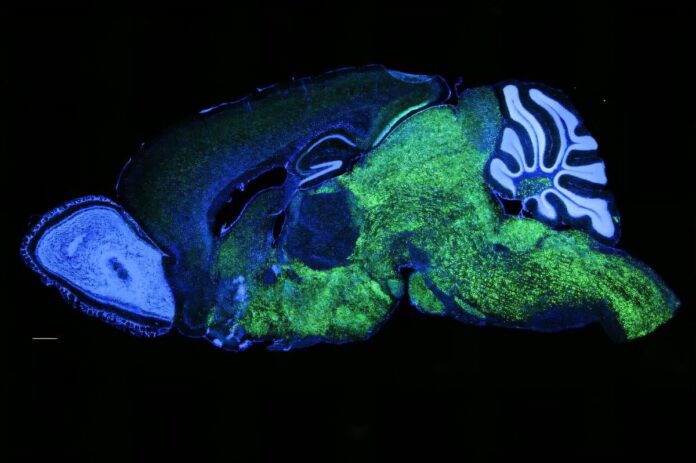

Cells producing the NOVA1 protein are shown in green in the brain of a mouse. A specific variant of this protein is unique to humans, and researchers suggest it is linked to spoken language development.

Laboratory of Molecular Neuro-Oncology at The Rockefeller University

As far as we know, modern humans are the only species capable of complex language. While scientists broadly understand the evolution of the anatomical features and neural networks in the brain that are crucial to this ability, the genetic component of speech has remained elusive.

Now, however, geneticists in the U.S. have discovered a protein variant unique to humans that might have played a significant role in the emergence of spoken language. When the researchers put the human-specific version of the protein, called NOVA1, into lab mice, the animals squeaked at each other in different, more complex ways.

“I definitely do think it is an important finding for the evolution of speech,” Wolfgang Enard, an evolutionary geneticist at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich who was not involved with the study, tells Science’s Ann Gibbons. The findings were published last week in the journal Nature Communications.

Genes determine the order of amino acids, which make up proteins. The NOVA1 gene carries instructions for creating the NOVA1 protein that’s key to brain development. First discovered by Darnell in 1993, the protein is found in many animals—but the specific version found in humans is unique.

The researchers discovered that even long-extinct close human relatives such as Neanderthals—who likely had the anatomical features for speech and carried a variant of another language-linked gene—had the “animal” version of NOVA1.

This suggests NOVA1 in humans developed into what it is today after Neanderthals parted from our lineage around 500,000 years ago. In a database of more than 650,000 modern human genomes examined by the team, all but six people had the altered NOVA1 protein. (Scientists don’t know who those six individuals are.) Researchers suspect the change—just one amino acid switch—provided enough evolutionary benefits to beat out the original version of the gene.

“This gene is part of a sweeping evolutionary change in early modern humans and hints at potential ancient origins of spoken language,” senior author Robert B. Darnell, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Neuro-Oncology at Rockefeller University, says in a statement. “NOVA1 may be a bona fide human ‘language gene,’ though certainly it’s only one of many human-specific genetic changes.”

It was one of the genes “that contributed to the emergence of Homo sapiens as the dominant species, which we are today,” Darnell adds to the Associated Press’ Laura Ungar.

For the study, the researchers used CRISPR gene editing technology to replace the NOVA1 protein found in mice with the human variant. This swap led to the production of 200 new proteins in the rodents, many of which are linked to how animals make sounds.

“For me, that was like, ‘Bingo!’” Darnell tells the New York Times’ Carl Zimmer.

The mice with the human version of NOVA1 began squeaking differently, especially male mice calling out to female mice. Overall, their squeaks were more complex, and the squeaking patterns became more intricate. Even baby mice calling to their mothers produced new sequences of sounds.

“All baby mice make ultrasonic squeaks to their moms, and language researchers categorize the varying squeaks as four ‘letters’—S, D, U and M,” Darnell notes in the statement. “We found that when we ‘transliterated’ the squeaks made by mice with the human-specific … variant, they were different from those of the wild-type mice. Some of the ‘letters’ had changed.”

In addition to shedding light on the evolution of human language, researchers say that gaining a deeper understanding of NOVA1 could have important implications for studying speech disorders.

The study is “a good first step to start looking at the specific genes” that might impact speech and language development, Liza Finestack, an expert in speech-language-hearing sciences at the University of Minnesota who was not involved with the research, tells the Associated Press.