Buried deep within a Portuguese rock shelter some 28,000 years ago, a small child’s ochre-stained bones whisper a tale of interwoven ancestries, ritual significance, and a culture lost to time. When the “Lapedo Child” was unearthed in 1998 in the Lagar Velho Valley, it upended long-held assumptions about Neanderthal extinction and human evolution. The child, whose skeletal features bore striking hallmarks of both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, seemed to embody the genetic legacy of ancient interbreeding between the two species. But an enduring question haunted the discovery—how old, exactly, was this burial?

For over two decades, the dating of the Lapedo Child’s remains has been a scientific puzzle, mired in inconsistent radiocarbon results and debates over contamination. Now, a new study by Bethan Linscott and colleagues, published in Science Advances, has used a novel form of radiocarbon dating to resolve this issue once and for all. Their findings not only refine the timeline of this enigmatic burial but also challenge prior assumptions about burial practices and ritual behaviors in Upper Paleolithic Europe.

Radiocarbon dating has long been the gold standard for establishing the ages of ancient remains. But when applied to the Lapedo Child, earlier attempts yielded wildly inconsistent results, ranging from 20,000 to 26,000 years ago—a discrepancy that made it difficult to place the burial in the broader context of human prehistory.

To solve this conundrum, Linscott and her team turned to a more refined method: compound-specific radiocarbon analysis (CSRA), specifically targeting the amino acid hydroxyproline, which is unique to bone collagen. Unlike conventional radiocarbon techniques, which can be affected by environmental contamination, this method isolates and dates only the endogenous material from the original bone.

The result? A precise date of 27,780 to 28,550 years before present (cal B.P.), placing the burial firmly within the Gravettian period of the Upper Paleolithic. This confirms that the Lapedo Child lived thousands of years earlier than some prior estimates and aligns the burial with other Gravettian mortuary traditions across Europe.

“The new hydroxyproline radiocarbon date for the Lapedo child is consistent with the original estimate of the burial event (~28 to 30 ka cal B.P.),” the authors write, highlighting the success of their new dating method.

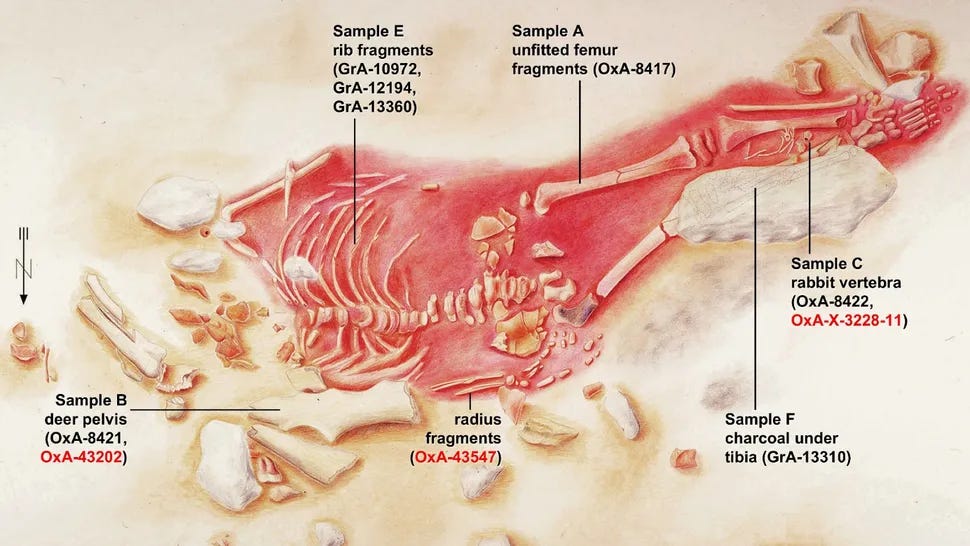

Beyond its implications for dating, the study also re-examines the ritual significance of the burial. Earlier research suggested that a juvenile rabbit’s remains, red deer bones, and charcoal found near the child indicated a carefully orchestrated funerary rite. However, the new dating evidence challenges this interpretation.

Redating these associated materials revealed an unexpected result—the red deer bones were actually older than the child’s burial. This means they were not placed in the grave as ritual offerings, as previously thought, but were likely already present in the sediment. Similarly, the charcoal under the child’s legs, once hypothesized to be evidence of a ritual fire, turned out to be at least 150 years older than the burial itself.

These findings force a reassessment of the symbolic elements of the burial. While ochre staining—commonly associated with Upper Paleolithic funerary rites—remains a strong indicator of ritualized treatment, the absence of directly associated grave goods weakens the case for an elaborate burial ceremony.

“The greater age of the red deer bones and charcoal suggests they were pre-existing in the sediment rather than intentionally placed,” the study notes.

From the moment of its discovery, the Lapedo Child’s skeleton was recognized as extraordinary. The child’s robust limb proportions and stocky build resembled those of a Neanderthal, yet their chin and other cranial features were unmistakably Homo sapiens. This mosaic anatomy reignited debates about the extent of interbreeding between Neanderthals and early modern humans.

In the late 1990s, before the Neanderthal genome was sequenced, the idea that modern humans and Neanderthals had interbred was controversial. Today, we know that most people of non-African descent carry small percentages of Neanderthal DNA, supporting the idea that hybridization did occur. The Lapedo Child provides some of the earliest skeletal evidence of this process in action.

While no ancient DNA has been extracted from the child’s remains—due to poor preservation conditions—their morphology strongly suggests that they were the offspring of a human-Neanderthal mixed lineage. The new dating reinforces this hypothesis, placing the burial firmly in the window of time when Neanderthals had disappeared from much of Europe but still left genetic traces among early Homo sapiens populations.

“On the basis of morphology, the Lapedo Child represents one of the earliest known hybrid individuals,” paleoanthropologist Adam Van Arsdale, who was not involved in the study, told Science Advances.

The revised chronology of the Lapedo Child is more than just a correction of an old date—it reshapes our understanding of Upper Paleolithic Europe and the transition from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens. The new evidence suggests that early modern humans in Iberia maintained burial traditions similar to those seen across Europe, even as they carried traces of a vanished lineage.

More broadly, the success of hydroxyproline dating offers a powerful tool for re-evaluating other problematic sites, particularly those where contamination has complicated past radiocarbon efforts. If applied to other ambiguous burials, this technique could clarify many lingering debates about human migrations, cultural transitions, and interactions between species.

“The application of hydroxyproline dating to the Lapedo Child demonstrates its effectiveness in resolving long-standing chronological ambiguities,” the authors conclude.

The Lapedo Child, frozen in time under layers of sediment and ochre, is more than an individual—this small skeleton represents a moment of profound transition in human history. The new dating study confirms their place in a world where modern humans and Neanderthals had only recently coexisted, exchanged genes, and shaped each other’s evolutionary destinies.

In revising the age of this burial, science has not only fine-tuned a crucial piece of the prehistoric puzzle but also opened the door to a more nuanced understanding of how we, as a species, came to be.

Perhaps, in the careful red-staining of a child’s bones, we glimpse something universal—the enduring human instinct to honor our dead and to weave meaning into their final resting place.