“I have tended to meet women a little coolly, and prefer to define a relationship in advance as an episode. Most women respond well to that, sometimes so well that I’m not just surprised, but a little hurt.”

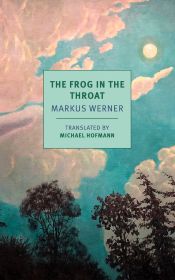

The Frog in the Throat, by Markus Werner (translated by Michael Hofmann), is the second of the late author’s seven novels. It was first published in 1985 and this new translation is being released under the NYRB Classics imprint. In alternating chapters it is narrated first by Franz Thalmann – a disgraced priest and now counsellor – and then Franz’s father, Klemens, who ruminates life’s mysteries as he hand milks the cows on his family farm in small town Switzerland.

The story being told from the two points of view open with Franz. Once a month he is bothered by a frog in his throat, an affliction lasting exactly three days that he believes is caused by his father who died six months ago. Klemens cast his son aside when he learned of an infidelity that cost Franz his job and marriage – a source of family pride thereby turning into a source of shame. Franz, now forty-nine and divorced for a decade, does not exactly regret his fall from grace. He has built a new life for himself, one he can be mostly comfortable with. As he gargles and swills in his attempts to draw breath he cogitates on his life and how he responded to the demands of family growing up, and of society in general.

Klemens, just before his death at nearly eighty, had become something of a kvetch. He blames modern parents for the behaviour of their children, falling short of taking any blame on himself for the choices his son made. Klemens buried his wife and daughter many years ago, the latter leading him to question God and faith. His father and brother died from suicide; another son suffers severe depressive episodes.

Although regarding themselves as fond of their wives, none of the men in this family appear to hold a great deal of respect for women as potentially generous people.

What we have here then is two generations looking back on their lives and how there were moulded by expectation. Subjects drift in and out of their consideration: men, women, desire, love, marriage, parenting, aging, manners, greed, politicians, crime, fame, television. As they postulate why attitudes have changed the reader may ponder the likenesses between their wider thinking.

“I often say to myself: God doesn’t want to be promoted like shoe polish, He dislikes propaganda, He would rather we were just decent people and go easy on His creation.”

Although clearly blinkered there are many truths to consider in these wide ranging musings. Both men have their failings – what Klemens did to the cat when his wife died is horrific – but neither are rare in any ordinary community.

An enjoyable read for the lens through which these characters view the world in which they have lived. There is humour and pathos but also nuggets of universal truths.

The Frog in the Throat is published by the New York Review of Books.