Article begins

Over the past decade, revelations of the scale of historical infant and child mortality and unmarked, improper burial at Ireland’s Mother and Baby Homes (state-funded, religious-run institutions for unmarried mothers and children that operated from 1922 to 1998) have sparked public outcry, memorialization, and calls for forensic investigation. At this year’s commemoration at one such institution’s graveyard, Bridget, a mother in her eighties, was too emotional to read aloud the poem she had selected for the day, Yeats’ “The Stolen Child,” in which faeries lure children of this world to a better one in a changeling metaphor for death. Against the neat, modest headstones of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, she recounted her own story instead: working in the labor ward without pay or any notion of the “facts of life,” and giving birth to William, a son who died. Her child is not buried there. In fact, nobody knows where the children are buried. But nobody believes, back then or now, that faeries have them.

From the audience, as an anthropologist-in-training afraid her fieldwork would amount to nothing, I was thrilled to hear a cultural-historical reference on the nose enough for me to easily interpret (ventriloquize?). The fantasy of Romantic Ireland denied again, against the reality of deprivation and Catholic morality during a difficult twentieth century. One mother’s real life, narrated in her own words, replaces a beautiful metaphor before the crowd. Good material for an essay like this one.

Instead of that essay, I reflect here on the problematic my response in this anecdote highlights: balancing the patterned resonance of history and the total singularity of each life, in attempts to name and redress harm done at Mother and Baby Institutions (“M&BIs”) and in ethnographic work.

Credit:

Phoebe Whiteside

The memorial garden at the Tuam children’s burial ground, referencing 796 deceased resident children with missing burial records.

The institutions widely known today as Mother and Baby Homes were one subset of quasi-welfare institutions that made up Ireland’s post-independence social care infrastructure. Following the dissolution of the Poor Law and associated Poor Law Unions (administrative areas for the implementation of the former, each with its own workhouse ) with the emergence of the Irish Free State after 1922, “county homes” inherited the mandate to administer to the destitute and sick on a regional basis. In alignment with the Irish Free State’s embrace of Catholic morality and identity as a counter to England’s colonial influence, a range of state-funded but religious-run institutions would fill the gaps in state care over the course of the rest of the twentieth century to come. Different religious orders with charitable missions in nursing, teaching, and the care of the poor received grants or capitation payments to run industrial schools for poor, orphaned, or otherwise disadvantaged children; “homes” for unmarried mothers and their unborn or young children, who were socially stigmatized; and orphanages. Some orders ran for-profit laundries in association with “Magdalene asylums” that forced institutionalized “fallen women” to work without pay. Since the 1990s, the open secret of poor conditions, neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and forced labor in many of these institutions has become no secret at all.

The infant and child death that took place at M&BIs in particular was thrust back into public consciousness after a local historian, Catherine Corless, published her finding that 796 children who had died in “the Home” in Tuam, which closed in 1961, lacked burial records. She further suggested, based on records, building plans, and local knowledge, that a subset of them might have been buried in a Victorian-era sewage containment structure on the grounds, a hypothesis later confirmed and qualified in a survey and test excavation led by archaeologist Niamh McCullagh and colleagues. When information about the disturbing nature of the unmarked common grave hit the international press in 2014, a scandal was born. In years since, through survivors’ and family members’ support networks, an official commission of investigation, and a burgeoning memoir genre, the M&BIs have taken their place alongside industrial schools and Magdalene Laundries as sites of contested memory in what historian James Smith has called Ireland’s “architecture of containment.” In Tuam, excavation is now imminent. Survivors, family members, and advocates continue to work for further investigation and redress connected to other M&BIs, like Bessborough, the institution referenced above, where the remains of over 800 children are missing.

Credit:

Phoebe Whiteside

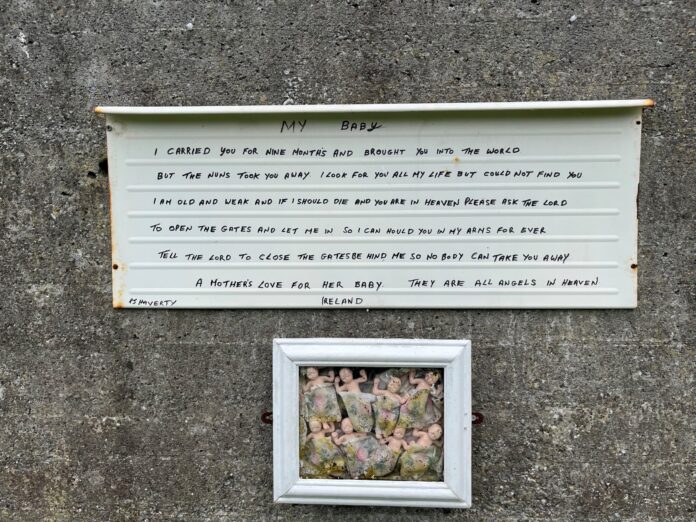

Poetry by P.J. Haverty posted at the Tuam children’s burial ground.

Who is responsible for the deaths and burials of so many innocents? Upon my various visits to the Tuam Children’s Burial Ground, poetry mounted to one extant stone wall called out the nuns for taking away children who are now “angels in heaven,” as baby shoes, toys, and rosary beads, soaked with rain, surrounded the Virgin Mary in her grotto in the corner. Church apologetics, and to a lesser extent the final report of the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation, suggest that society as a whole was at fault. This statement might seem at first glance to be in line with an account that considers history and cultural conditions. But many people affected by M&BIs reject the diffusion of responsibility this explanation implies; its vagueness does not hold the state and church accountable for systemic but specific actions. The question for me, as an anthropologist, then becomes: how do my interlocutors parse recurrence and exception as they talk about what happened at the M&BIs and advocate for, or participate in, forensic intervention or other forms of redress? How shall I?

As an observer, it is easy to desire resonance with history that offers something in the way of an empirical structural explanation, or poetic parallel structure. At the site where the Tuam M&BI once stood, it’s not too hard to find it, in bits and pieces. When I spoke with another early Tuam whistleblower, she quoted for me the words of a local man who, as a boy in the 1970s, had stumbled upon a hole in the ground that appeared to contain hundreds of tiny bones, “like something out of the National Geographic.” The remains were thought to be those of famine victims, from the building’s time as a workhouse, blessed and covered up again. There are, indeed, burials from famine times that have been excavated within the boundaries of the former grounds. Another partial comparison is with cillíní, or killeens, separate burial grounds historically used primarily for stillborn and unbaptized infants, whose burial in consecrated ground was proscribed by the Catholic Church. The analogy fails because, of course, the children of the Tuam institution were often older, certainly baptized, and born during decades when this practice had begun to die out. Their burial is better understood as a common or mass grave. But some mutual influence persists: one Tuam-affiliated support group organizer, Catriona, spoke to me at length about the work she was doing to mark and honor her own family’s cillín, alongside her efforts towards awareness and redress with survivors of the institution. Over a networking coffee, an archaeologist who maps cillíní in several Northern counties told me that in fact it had been the Tuam children’s burial ground that inspired her research in the first place. Another map can be drawn—has been drawn, at least in part, by historians—linking class and nation and church and gender across the decades in a way that might explain both the context of famine and children’s burial grounds and the conditions for what happened in Tuam. Lest I misrepresent the domain of historical and structural explanations, they are alluded to also by women like Elizabeth*, whose sibling died in the Tuam institution, in her indictment of institutions that “ran on the blood, sweat, and tears of the innocent poor.” These conditions are important. But then, how do you “explain” a child’s death? Visiting from America, where the great famine and rules about burial in consecrated ground are referenced more often as history than memory, how much right do I have to gesture at attempts to do so?

I find some examples in the way various survivors, relatives, and their advocates have narrated their experiences and opinions in our conversations. They prioritized the singularity of a child’s life and social relationships without losing sight of broader social-historical conditions by refusing to treat history as something entirely past—or, indeed, to see these events as falling under the remit of historical and archaeological sciences. Two examples will suffice. First, when the government office tasked with the Tuam excavation initiated an early DNA sampling campaign for elderly and sick presumed relatives of children in the grave, the genetic kinship analysis provisions of the 2022 Institutional Burials Act became an object of contention. Catriona, Elizabeth, and Mary, who was born in the Tuam institution, told me about their frustration with the exclusion of cousins from the list of relatives eligible to provide samples. This exclusion was suspected of signaling an inappropriate delimitation of which family members “counted,” a failure to fully invest in identifying the children by using the latest technologies, or both. Whether or not this was originally an artifact of technical limitations, an oversight, or an otherwise intentional exclusion, my interlocutors’ response to the decision prioritized the relational obligations of family and government participation in the present over procedural precedent. A similar priority was evident in my conversation with Julie, who works closely with relatives of the deceased and survivors in her professional capacity. After expressing her conviction that the planned forensic intervention was necessary despite not expecting that every child would be identified, she redirected attention to truths that neither forensic science nor historical research can address in the first place:

“Because the truth has been hidden and lost, we’ll never know, as I said to you, the little details, but important details. Who was with the child when they were passing. Did they get a prayer? Did they get a poem? Did they get a cuddle? Did they get a kiss? Did they dress them nice? Did they wrap them up? Did they place them into a coffin or just into the ground? Maybe there were no coffins. […] These are things we will never, ever get the truth to. What did the child really die of? What’s the cause of death? What was the ritual? Yeah, so all that stuff is lost.”

The anthropologist Miriam Ticktin writes about the quality or category of innocence as our collective criteria for the perfect recipient of humanitarian care. Her argument has to do with the pitfalls of this, its tendency to impose hierarchies of deservingness and humanity, and possibilities otherwise. It seems, today, easy to figure the Tuam babies as icons of innocence. And there is something of Ticktin’s argument in the way, some of my interlocutors tell me, the public tends to be more interested in their plight than in that of their mothers. But in this context, there’s a twist: in the moral rescue discourse of the time, itself a precursor to the new humanitarianism Ticktin examines, the status of these children was quite ambivalent. They could be seen as a threat to society, just like their mothers. Her argument stands, but in this light, does the contemporary affirmation of their innocence not also take on a different quality?

At the time of writing, preparations for a long-awaited excavation are underway at the Tuam children’s burial ground site. Just around the corner and across the road lies the main town cemetery, still in active use. When I visited last summer, I noticed a proliferation of little graves, marked as new by their materials and shine, in one otherwise sparse corner. But the dates, indicating ages at death of one, three, six years old, clearly predated the headstones by at times fifty years or more. It would seem that there is a change underway that exceeds a gradual shift in burial customs: to reinsert each of these individual children into history, or perhaps to act on that past, as a parallel present, rather than offer it as explanation.

Note: All names other than those of public figures have been changed.

Lauren Crossland-Marr is the section contributing editor for the Society for the Anthropology of Europe.