“Gaming” is conceptually branching out. It “virtually” overlaps with museum visuals and actively engages with lived cultures and heritage. Both developments point out that perhaps even with the prevalence of computation, there is still something we can learn from sociocultural anthropology, especially the anthropological ways of writing cultures – ethnography.

When Anthropology Meets the “Virtual”

Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design presented by MoMA between 2022 and 2023 is probably one of the few major exhibitions to summarize trends across the gaming industry in terms of design and user experiences. But art institutions were by no means the first academic realm to have a take on gaming. Back in 2019, Never Alone (2014), the adventure game reinterpreting the Iñupiaq tale of Kunuuksaayuka that the MoMA exhibition included and took its title from, was featured at the Game Developers Conference. As part of a panel discussion, titled “Keeping It Real: Authenticity, Anthropology and Artistry in Interactive Narrative,” game developers went over the nitty-gritty of interactive games in relation to the ethnographic scene, from tracing traditions of a lesser known community to first-hand immersion in local ethnoscapes. It seems, the way anthropology can draw on facts to forge stories more captivating than the facts themselves is still in use during postcolonial times–to convey more veracity and depth to the fundamentally not-real-life Human-Computer Interaction (HCI).

When it comes to what best reflects humans and their cultures, every discipline has their own theories on “authenticity.” Anthropologists, for one, use “the social” to denote an established set of practices, beliefs, and norms shared among communities. In an age when digital interfacing became more and more prominent, “the social” has come to include simulated interactions that display similar patterns as in-the-flesh social lifes. In Coming of Age in Second Life (2008), anthropologist Tom Boellstorff expanded the concept of “play” and play behaviors to role playing using simulators, or “sims,” taking place in the virtual world. Boellstorff would end up (2008) arguing, by gathering fieldwork materials interacting with other simulated characters, that the social exchanges and consequences, as well as the existing notions we have about time and space are still in full effect when we go virtual. A decade later, the use of anthropological methods in game development have proven that the reverse statement is also true: The emergence, formation, and repercussions of virtual worlds are recollections of our thoughts and activities from real life. And little by little, the act of navigating the interactive media scapes has been associated with another parallel activity already with plenty of ethnographic connotations: walking (Ingold and Vergunst 2008).

Walking vs. Wandering

Decades have passed since scholars have been exploring the cultural contexts of walking in real life, from the Situationist International’s use of walk to recover subtle, quotidian relations with our lived environments (De Certeau 2013) to the ethnographic use of walk as a way to trace the qualia to denote types, genealogies, or semiotics (Chumley and Harkness 2013) and even, in a more micro sense, significant traits within sites, space, and time. Yet, how walking could be situated in digital media is a relatively new topic. In Wandering Games (2022), interactive media scholar Melissa Kagen compares walking and wandering. Walking is, in a way, indicative of activities in “walking simulators,” a term initially used to denigrate slow-paced, single-player games. Kagen (2022) argues that walking provides meaning-making.“The purposeful speed walks of Amazon warehouse low-wage workers [racing] around facilities [and] the virtual wanderings of players who roam around digital worlds and use them to make meaning” (1), the comparison she draws, indicated that there is a difference between literal routed walking and the more rambly navigation across scenes designed for interactive games, namely gamescapes. This lies in the implications of not walking a designed path, and being forgiving to deviations, which is now believed to “serve for debates about anti-game aesthetics […] and the potential of poetic storytelling” (Kagen 2022, 2).

So, walking has been an interactive activity even before adventure games. And it is safe to say that, when interactions no longer involve real-life geographics, wandering in such a world becomes a reverse-engineering process that relies on the presentation of an artifact, composed of defining elements human societies have long believed to be indispensable to our landscapes, storytelling, and characters. Hence, walking became wandering and thus the antithesis of “hardcore” MMOs is not merely capitalism’s doing. There’s something more poetic in it than the erosion of our everyday lives by hustle culture. It was only an afterthought for human subject research to snowball their data based on tactile senses, locomotion, as well as visual stimuli, like the way Tim Ingold (2000) approached landscapes. But Ingold did bring up something along the lines of wandering, as he parsed navigating landscapes as both getting a sense of our surroundings and being at peace with our own psyche.

Maybe we could understand the rise of “walking simulators” as a recent twist of a three-dimensional iteration of a psychogeographic map, which also, in turn, could be an ethnographic subject and a vessel for participant-observers called gamers to breathe new life into it through their individual gaming practices.

Sight and Site

Ethnography’s role in game design was not just about the storytelling from which one can build not only stories but also worlds and cosmos. Ethnography is also a blanketing term for ways of describing human intellect and psyche and approaches to making the above more lucid. Beyond the MoMA exhibition and the more specialized academic interpretations of adventure games, there are many more cases in the 2010s that showcase how game development has leveraged the latter strength via experimenting with the lenient mechanics of wandering. One example is Life is Strange (2015), a story that takes place before an imaginary storm, a typhoon that will destroy the whole town. But besides the archetypal chaos theory that the game anchored its storytelling on with a parallel between the storm and the blue butterfly, aka “the butterfly effect,” Life is Strange (2015) is a reflection on today’s media industries and its relation to the archaeological digging that has been done–academically or not–on analog media.

In Life is Strange (2015) the player character, Maxine “Max ” Caulfield’s “rewind” skill (or time-shifting powers) is a nod to analog films–how most Daguerreotypes are “fixed.” Screenshot by author.

During the early- to mid-2010s, anthropologists started to explore photography’s potential to be turned into ethnographic materials, especially as the practice connects the dots between realistic portrayals of persons and the revelation of the human psyche by way of how an image is framed. Daguerreotype became radicalized (Edwards 2015), and selfies were “consecrated,” according to author André Gunthert, as powerful “auto-photography” that brought forth a whole “genre powered by digital autonomy” (2015, 8), and infested by pornification. Life is Strange (2015) touched upon all the topics. The player character, Maxine “Max ” Caulfield’s “rewind” skill (or time-shifting powers) is a nod to analog films–how most Daguerreotypes are “fixed” and brought to clarity using an arduous chemical process–as Life is Strange (2015) translates the precarity of analog photography techniques into the precarity brought by multiple options and many unknown way to bring back memories that could change the present. Meanwhile, the photographic object, now a symbol of the outcomes of a choice, has personal and societal values that frame the character: her point of view, her artistic expression, and her life journey, alongside traces of inequity within the creative industry.

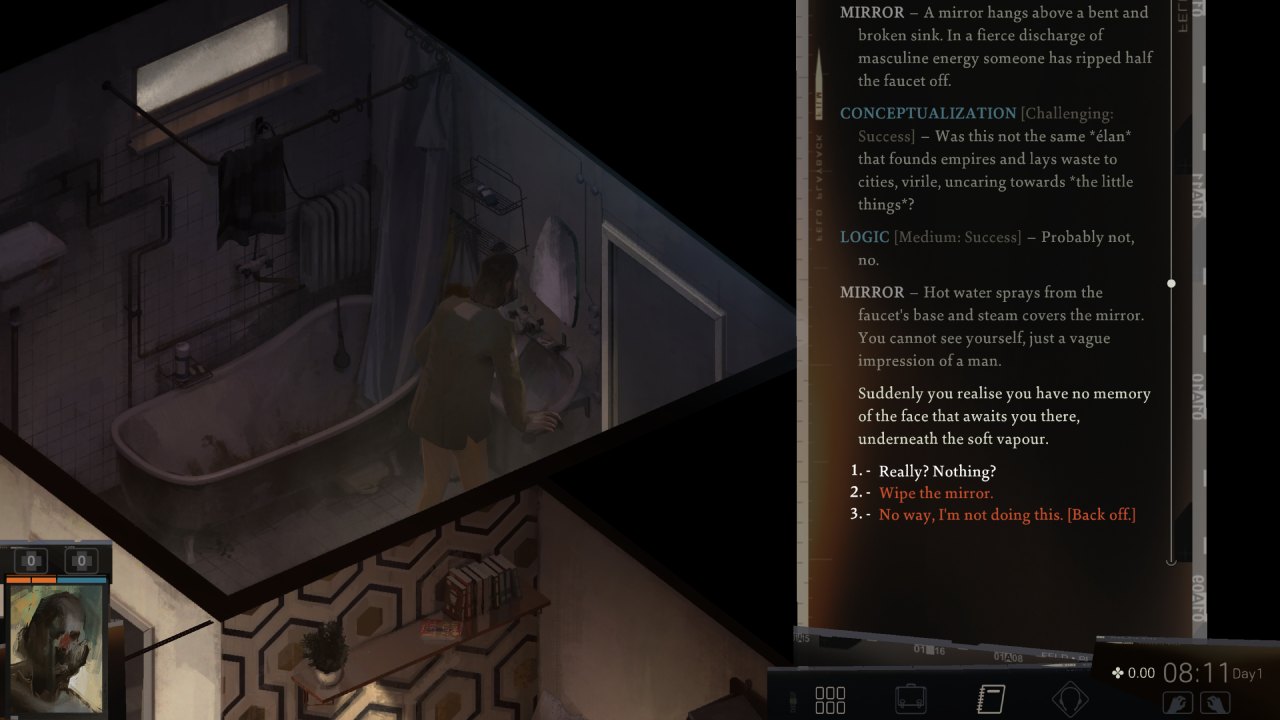

Similar to Life is Strange (2015), Disco Elysium (2019) transposes political theory into an RPG that caters to a detail-obsessed glance related to the discipline. Martinaise encapsulates a psychogeographical map–and a territory marked by using and rambling. Each day, you are discovering your identity, which began with a Freudian “look at yourself” mirror stage. Alongside thought bubbles that appear as you move along the map, the skill points or personal development gained will inform the player’s analysis and, thus, impact on the outside world. Underlying story arcs suggested by postcards and ephemera could open up to archaeological digs, or make up cabinets of curiosity. To bring a no longer modifiable historical course back to life has been the goal for the Estonian teams–and the gameplay is essentially a window for players to participate in it and witness the possible consequences or calamities of political choices.

In Disco Elysium (2019) you are discovering your identity, which began with a Freudian “look at yourself” mirror stage. Screenshot by author.

The Journey In-Between

There are, also, walking simulators foregrounding less of a social phenomenon or grand narrative. For example, the recently released Open Roads (2024) entertains the practice of walking in and of itself in a road trip as it touches upon traces of mother-daughter relationships through items from an old summer house. Despite the abundant mid-twentieth century elements (including countercultural memories) present–ranging from old photographs, letters, and pottery works, to family correspondence letters –these objects are not necessarily catering to the viewpoint of an anthropology practitioner. Instead, the simulated walk to pick up and pack up “things” nudged players to rethink the many factors that could blur the line between objects and artifacts and consequently, trivialized everything through simply the act of “putting [them] away.”

On the other hand, less eventful plots could bring up confrontational feelings and reveal transient relations that possibly could come to one’s aid. Realizing the sophistication within the mundane is what Anthropologist, Professor Rosalind Morris (2018) believes to be the starting point of a creative storytelling process. Morris (2018) argues we need to embrace an urge to go “against technical reproduction [and] competing with the storyteller’s narrativity” (107). This raises the question: Could going beyond copying and upgrading technology bring out what we have not yet understood about ourselves and our histories? Thoughts on poignant pasts, memorable flashbacks, and messages we find that might deserve to be passed on… In a virtual landscape, this mix of intentions composes and, more importantly, enables a worldbuilding that gets people out of their limbo. This is the self-justification for the many low-productivity “virtual lives” spent, and tangentially, I figured, the reason many game developers have opted for meaningful walking simulators, too.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Iván Flores.

References

Boellstorff, Tom. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press,

2013.

Ingold, Tim, and Jo Lee Vergunst, eds. 2008. Ways of Walking : Ethnography and Practice on

Foot. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment. Routledge, 2002.

Kagen, Melissa. Wandering Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022.

Morris, Rosalind C. “Shadow and Impress: Ethnography, Film, and the Task of Writing History in

the Space of South Africa’s Deindustrialization.” History and Theory 57, no. 4 (December 2018): 102–25.