A moose mating ritual

“Sorry, what did you say?” asked the company CEO during a meeting about new regulatory requirements. I repeated, “We need to map moose wallows. It’s part of the Treaty 8 Planning and Mitigation Measures Guidance issued by the British Columbia Energy Regulatory “BCER”.[i] The BCER is the energy regulator for the province of British Columbia in Canada. Nearly a year in the making, the guidance they issued served as a new solution to implement the recent Cumulative Impact order put in place by the province (2024).[ii] The new requirement did not make immediate sense to those in the meeting, consisting of the management team of a junior energy company working in northeast British Columbia “NEBC”, with whom I sat as a sustainability officer. While most of my colleagues had in fact seen a moose before, being city folk living nearly 1,000 kms from the terrain of corporate operations, we all knew very little about moose habits. With the help of Google, we had our questions answered. All-about-moose.com/moose-wallows.html explained it thus:

A moose wallow is a pit the bull moose creates during the mating season, usually made by the dominant bull of the area. He makes it by pawing with his fore feet, scraping the ground.

The result of his pawing creates a depression in the ground over which the bull positions himself and subsequently urinates in. He will often immediately lay down in this perfumed mix to get as much scent from the wallow onto his body as he can. He does this much like a man wears cologne to attract a mate. …When a bull lies in his own wallow, cow moose find this almost irresistible.”[iii]

Filling the end of day elevator descent with talk of this unexpected learning, some of my colleagues dared others to test out moose mating rituals on their wives. While the lighthearted laughter soon wore off, the more serious learning that moose wallows were crucial to moose populations, and to Treaty Rights stayed with us.

Cumulative Dispossession

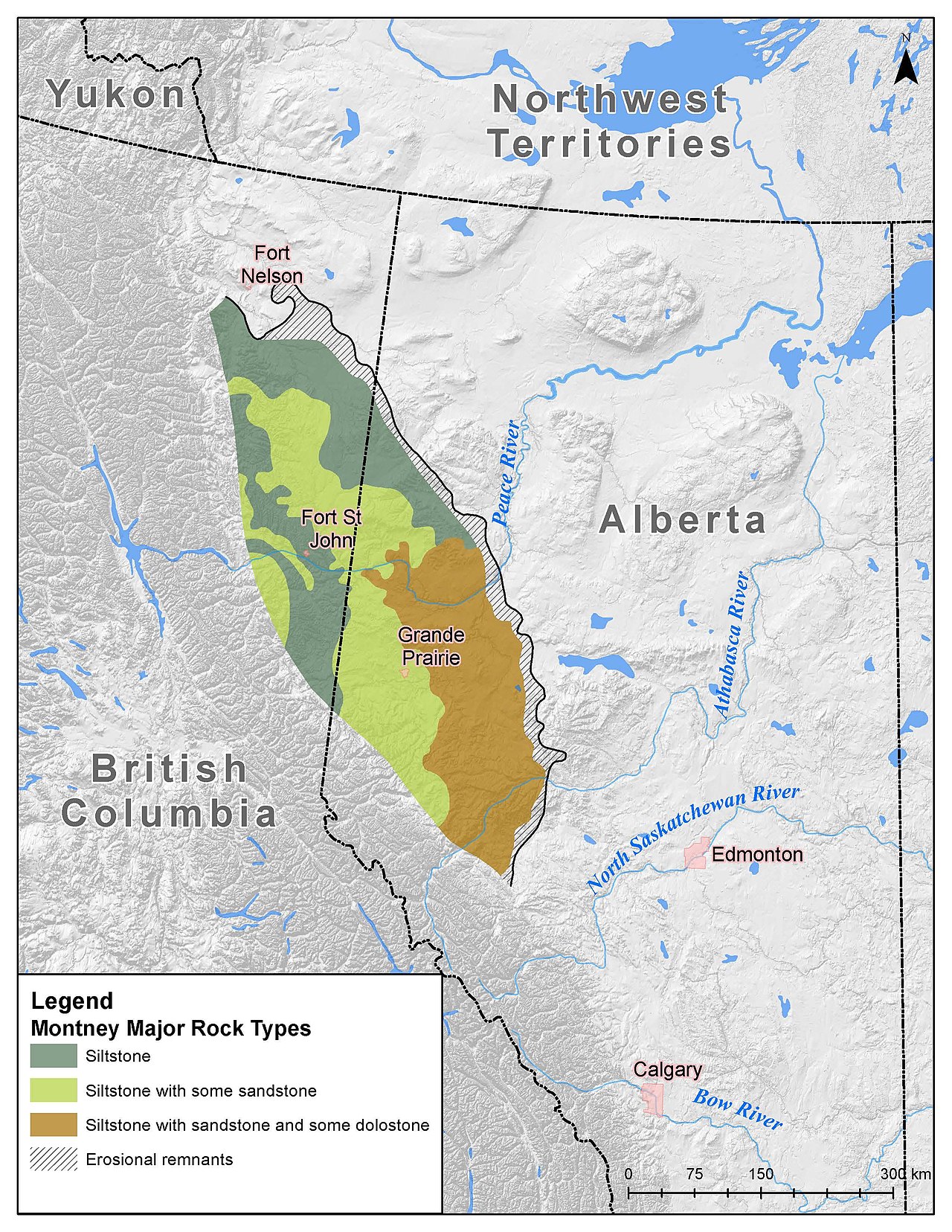

The many new multiwell pads in NEBC likely haven’t gone unnoticed by moose and bear populations. NEBC is atop the prolific Montney formation, a resource play comparable to the Permian or Eagle Ford formations in the USA, known for vast deposits of shale and siltstone and long-life reserves. Market participants often refer to this region as the Mega Montney or the Montney Python, and more as Canada’s “natural gas powerhouse, “highlighting its sheer scale and “multizonal stacks of opportunity” that extend through four stratigraphic subterranean layers or ‘benches’ (as industry refers to them) that total up to 300m thick across an oval-shaped land mass that is approximately 130,000 square km.

There are over 10,000 active wells in BC, most of which are tapping the Montney. The BCER (2023), estimates the BC Montney formation to contain at least 271 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of recoverable natural gas reserves, and approx. 83 million barrels (bbls) of recoverable oil reserves, and 1.68 billion bbls of natural gas liquids, including the high value condensate used as a diluent for bitumen. New technologies and discoveries continue to grow these reserve estimates. As Canada’s largest region of natural gas production, the BC Montney is slated by many to be a transition export fuel that can supply foreign markets via liquified natural gas “LNG” export as early as May 2025 from Kitimat.[iv] Currently five licensed LNG export projects (three are Indigenous owned or partnered) signal a widespread ambition for natural gas production, energy reconciliation, and natural gas export as future economy.

With only about 10% of its reserves recovered, the Montney is early life, meaning it can fulfill a long phase of potential extraction ahead. This is especially so given that the Montney is already ‘proven’ for its scalability, quality, repeatability, productivity and rates of return that readily attract capital to it.

It was with these qualifiers in mind that my interlocutors had formerly secured mineral tenure in the area and were now looking to mimic the logics of expansion through standardization, modularization, and repetition so preferred by both capital institutions and governance structures (Appel 2012, 2019; Tsing et al 2024). While current multiwell pads minimize land disturbance when compared to previous technologies that relied upon one well per location, pads require about 4.8 hectares of land. Pads are also scalar and connect to regional infrastructure. To generate promised returns, land is formed into a temporarily denuded enclave which then unfolds as an ‘anthropocenic patch’ (Tsing et al. 2024) with a new ‘second nature’ (Wheatley and Westman 2019, citing Cronon [1991]). Although shaped through strategies of mitigation that are designed to protect nature(s), culture(s) or ‘heritage’, these enclaves and their installations often leave a trace.[v]

The cumulative effects of development are what led Chief Marvin Yahey, representing the Blueberry River First Nation (BRFN) and other Treaty 8 First Nations in NEBC to sue the BC government for Treaty right infringement.

While any one multiwell pad or infrastructure project may on its own be fine, cumulative effects or “CEF” result from numerous, public and private coinciding resource and infrastructure projects (Amatulli 2022; Mason 2025).[vi] In fact, the cumulative effects of development are what led Chief Marvin Yahey, representing the Blueberry River First Nation (BRFN) and other Treaty 8 First Nations in NEBC to sue the BC government for Treaty right infringement (Amatulli 2022; Yahey vs BC 2021).[vii] The case alleged that overdevelopment in the area from multiple industries had infringed on Treaty Rights, especially given that one could not travel more that 500 meters in any direction in their traditional territories (defined in the case as the ‘claim area’) without encountering industrial development. After deliberating the evidence, Honorable Justice Burke of the Supreme Court of BC, sided with the BRFN. While the energy regulator had in fact devised a cumulative effects framework, no sufficient method of making use of it had yet been provided to decision makers.[viii] In an announcement that both admitted defeat and came as a surprise to industry, the BC Government did not appeal the case, opting instead to collaborate with First Nations on a new regulatory structure (BC Gov News 2021). Doing so would also bolster the province’s commitment to UNDRIP signed November 26, 2019 (Government of British Columbia 2022).

Undoing Cumulative Effects

Collaborations between BCER, BC Government and BRFN (now represented by Chief Judy Desjarlais, who had replaced Chief Marvin Yahey), resulted in the Blueberry River First Nation Implementation Agreement, announced in January 2023. The stated purpose of the agreement was to:

- “Initiate a new approach to resource management and the protection of Treaty Rights in the Claim area […]

- Balance Treaty Rights and the healing of the environment with a sustainable regional economy; and

- Reduce and remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere by limiting certain timber harvesting and other resource activities […] (2023)

To meet the terms of the agreement, the BC Government and the BCER collaborated with BRFN and agreed to install land tenure restrictions and a land disturbance cap that clawed back the crown land available for corporate development. Also agreed was a process to prevent piecemeal permit review; a new requirement for pre-application engagement to support the UNDRIP right to free prior and informed consent for Indigenous people with regards to projects on their lands; and a more fulsome and collaboratively designed cumulative effects management framework.[ix]

Guidance to industry on how to comply with the agreement came out in May 2023, and then additional guidance on mitigations and measures that would operationalize the management of CEF for industry came out in May 2024. Taken together, the new regulations would demonstrate action taken by the BCER to protect Treaty Rights and provide the BCER with data sets that would be legible to the courts and able to withstand future trial.

Of the new items announced in the agreement, the disturbance cap caused the biggest disruption to the energy industry’s business-as-usual. Some proponents feared the value of many mineral tenures had become stranded almost overnight, while other proponents would have to claw back some development plans to stay within their new annual disturbance cap allocations. This change would by no means end development in the region but would instead structure how development could continue, with First Nations in NEBC Treaty 8 setting guard rails around where, and when, development could occur. The agreement also called for new and frequent efforts by proponents to ‘heal the land’ through more frequent restoration, rewilding and applying traditional ecological knowledge and land use. While the public was not privy to the collaborations, their outcome certainly reconstituted surface regulations with a greater, though very contested, Treaty 8 First Nations point of view.

For example, four other Treaty 8 First Nations signed Consensus Documents with the BC Government to ensure their inclusion and co-development of a lands and resource management approach that would address cumulative impacts and the meaningful exercise of Treaty 8 rights in their territories (BC Gov News 2023, Jan 20). Yet, during fall in 2023, the Halfway River and Doig River First Nations both petitioned the BC Supreme Court, alleging that the BC Government had breached its duty to consult and that the Blueberry River Implementation Agreement impinged upon their traditional territories. A recent Settlement Agreement between Halfway River and the BC Government clarified the agreement areas among other provisions. At the time of writing, a settlement with Doig River on that matter remains outstanding. However, the colonial appropriation of the Montney Reserve and its minerals was recently addressed in the settlement of long-standing land entitlement claims between the BC Government and five Treaty 8 First Nations (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2023, April 15).

For proponents, the act of working with the new CEF regulations and the risk to permits by delaying, ushered in a new dimension of seeing Treaty Rights.

By the time this management team had its first moose discussion, a full two years had gone by since the Yahey case was tried—a period that was experienced by producers as suspended time filled with concerns about an uncertain market and potentially stranded capital.[x] This moose and its mating ritual was received in that context—as a rather urgent mammal of concern. Moose were now one of five CEF values (new regulatory objects) and potential actors aiding in the work of cumulative effects management that was staged to undo Treaty Rights infringement. Moose (and other roaming ungulates), wallows, mineral licks, trails, and other constituents of the natural surface world, including bears, aquatic/riparian zones, old-growth forests and biodiversity, would now require upfront consideration, mapping and setbacks, with additional setbacks for Indigenous traplines and hunting cabins. For proponents, the act of working with the new CEF regulations and the risk to permits by delaying, ushered in a new dimension of seeing Treaty Rights. In this way, through the successful assertion of Treaty Rights, First Nations were remaking proponent “subjects” and undoing some entrenched structural privileges of settler colonial petrocapitalism through the regulatory hands of the BCER.

Seeing Treaty Rights

In my experience oil and gas executives tend to think primarily about the subsurface. Maps depict layers of the stratigraphic subsurface that are, in the case of the Montney for example, 2-3km below the surface.[xi] Oil and gas onto-epistemologies fixate on the zones of commodity value, probability, profitability and capital efficiency in time (Field 2022; Wood 2016). Aside from the engineering feats required to accomplish extraction, the geographical surface can seem to be mere points of access to value that require rental and payment (long but not especially deep obligations). The subsurface holds the prize. Joly et al. (2018) refer to this eclipsed vision as a form of “cartographic colonialism”- a way of not seeing Indigeneity and settler colonialism. In this new BC regulatory regime, oil executives must now more fully see and oblige the Treaty and be present in pre-engagement meetings.[xii]

More than just following new rules and procedures, enacting ethical space carries the potential for agreement to be reached […]

Pre-engagement meetings resemble what Ermine (2007), and Crowshoe (2020), call ethical spaces. Littlechild and Sutherland (2021) operationalize the concept by using the notion of “Two-Eyed Seeing” shared by Mi’Kmaw Elder, Albert Marshall. More than just following new rules and procedures, enacting ethical space carries the potential for agreement to be reached, as Littlechild describes it, by beginning with empathy and an open heart, active contribution and active listening when one or more knowledge systems are at the table, and when finding an equitable and workable solution for all is crucial (ibid).[xiii]

The proponents I work with now have routine pre-application engagement meetings with Treaty 8 First Nations constituents. Within these newly made ethical spaces, meetings have become more meaningful because relationships are being made. We ask about each other’s families. We worry about the dangers of wildfires. Being present creates first-person interactions and accountabilities that are not possible when third parties act for proponents.

Amid these positive signals, proponents remain concerned over whether the process will offer more certainty to the investment market as it is unclear how long permits will take, or what will happen if things don’t go well, or if the new system exhibits any signs of failure.[xiv] At the same time, there is no mistaking the volumes of work that pre-engagement (in addition to consultation) requires of First Nations. Overworked First Nations land departments are now a new front line doing the regulatory work of vetting hundreds if not thousands of resource projects each year to prevent infringements to Treaty Rights or ensure mitigations for CEF potential.

Meanwhile, adding to these nascent effects of a new regulation, moose wallows and other CEF values are becoming more visible. Proponents tread with more care upon a surface that is riskier given that permits are at stake and morally thickened by new social relations and more-than-human obligations.

Featured image: Pixabay

Notes

[i] https://www.bc-er.ca/files/operations-documentation/Environmental-Management/Treaty-8-Planning-and-Mitigation-Measures.pdf

[ii] For Guidance on the Order see Cumulative Effects Guidance in Northeast BC: https://www.bc-er.ca/energy-professionals/application-documentation/cumulative-effects-guidance/#:~:text=The%20CI%20Order%20requires%20decision,activities%20on%20the%20treaty%20rights.

[iii] Thanks to this inquiry and the logics of algorithms I now get spammed with moose and elk rutting footage.

[iv] See: Canadian liquified natural gas projects.

[v] These traces can range from being a rather innocuous presence of a series of wellheads on a well-maintained lease, to an overgrown site of an abandoned orphaned well, or the rather large and ‘unnatural’ presence of a water storage pit, or the massive new natures of oil sands tailings ponds, for example (see Peric [2024] for an especially good illustration).

[vi] For descriptions of NEBC public and private Extractivist impacts see Willow (2020, 2018, 2016).

[vii] Treaty 8 First Nations in the province of British Columbia are: Blueberry River, Doig River, Fort Nelson, Halfway River, McLeod Lake, Prophet River, Saulteau and West Moberly First Nations.

[viii] For the prior CEF framework see, Regional Strategic Environmental Assessment (RSEA) Moose Core Effective Suitable Habitat [BCOGC-132738RHEA Report, 2018] and Grizzly Bear Infographic

[ix] For a description of the pre-application process see https://blueberryfn.com/departments-services/lands/pre-application-engagement/. It is noteworthy here that pre-engagement may establish a process for but does not equal ‘consent’.

[x] For discussions on the ethical orientations of energy executives, see High (2019) and Wood (2019).

[xi] For discussions on how oil executives see, see Bridge (2001), and Wood (2016).

[xii] By contrast to (but not that unlike) Ferguson’s (2005) assertion that capital hops over certain zones, here capital inhabited Treaty 8 lands but ‘hopped over’ Treaty Rights.

[xiii] This concept is used within Alberta’s oilpatch. I first came across it while taking a new course called Sustainability in Energy Microcredential by Geologic Systems, 2024.

[xiv] For one such signal, see: Statement regarding the decision to remove Judy Desjarlais from office – Blueberry River First Nations

References

Appel, H. (2019). The licit life of capitalism: US oil in Equatorial Guinea. Duke University Press.

Appel, H. (2012). Offshore work: Oil, modularity, and the how of capitalism in Equatorial Guinea. American Ethnologist, 39(4), 692-709.

https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2023PREM0005-000060

BCER. (2023, June). Guidance for BRFN Implementation Agreement Form (Version 1.0).

BC Ministry of Energy, Mines & Low Carbon Innovation. (2023, January 27). BRFN Agreement – Rules for Oil and Gas Development.

Bridge, G. (2001). Resource triumphalism: Postindustrial narratives of primary commodity production. Environment and Planning A, 33(12), 2149-2173.

Cronon, W. (1991). Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. W.W. Norton.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. (2023, April 15). Five B.C. First Nations reach settlement with the provincial and federal governments on Treaty Land Entitlement claims. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2023/04/five-bc-first-nations-reach-settlement-with-the-provincial-and-federal-governments-on-treaty-land-entitlement-claims.html

Crowshoe, R., & Lertzman, D. (2020). Invitation to ethical space: A dialogue on sustainability and reconciliation. In Indigenous wellbeing and enterprise (pp. 10-44). Routledge.

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193-203. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/article/view/27669/20400

Field, S. (2022). Carbon capital: The lexicon and allegories of US hydrocarbon finance. Economy and Society, 51(2), 235-258.

Ferguson, J. (2005). Seeing like an oil company: Space, security, and global capital in neoliberal Africa. American Anthropologist, 107(3), 377-382.

Joly, T., Longley, H., Wells, C., & Gerbrandt, J. (2018). Ethnographic refusal in traditional land use mapping: Consultation, impact assessment, and sovereignty in the Athabasca oil sands region. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(2), 335-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.03.002

Mason, A. (2025). Energy Capitol: The Waning of Regulatory Form. Routledge.

Peric, S. (2024, May 15-18). The soundscape of crisis: Bird and tailing pond life in Northern Alberta’s boreal. In Sedimented Histories, Vital Trajectories, Annual Meeting of the Canadian Anthropology Society. University of British Columbia, Okanagan, Syilx Territory.

Tsing, A. L., Deger, J., Saxena, A. K., & Zhou, F. (2024). Field Guide to the Patchy Anthropocene: The New Nature. Stanford University Press.

Wheatley, K., & Westman, C. N. (2019). Reclaiming nature?: Watery transformations and mitigation landscapes in the oil sands region. In C. N. Westman, T. Joly, & L. Gross (Eds.), Extracting Home in the Oil Sands (pp. 160-179). Routledge.

Willow, A. J. (2020). Destruction and disjuncture: Ironies of apology, exhibition, and ethnography along British Columbia’s dammed Peace River. Ethnohistory, 67(1), 49-74. https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-7888707

Willow, A. J. (2018). Understanding ExtrACTIVISM: Culture and Power in Natural Resource Disputes (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429467196

Willow, A. J. (2016). Indigenous extrACTIVISM in boreal Canada: Colonial legacies, contemporary struggles and sovereign futures. Humanities, 5(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030055

Wood, C. L. (2016). Inside the halo zone: Geology, finance, and the corporate performance of profit in a deep tight oil formation. Economic Anthropology, 3(1), 43-56.

Wood, C. (2019). Orphaned wells, oil assets, and debt: The competing ethics of value creation and care within petrocapitalist projects of return. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 25(S1), 67-90.

Yahey v. British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 1287. https://www.bccourts.ca/jdb-txt/sc/21/12/2021BCSC1287.htm

Abstract: Guided by a notion of regulation as world-making, this paper chronicles changes to the regulatory landscape of northeast British Columbia (BC), Canada, where the historic legal case, Yahey vs. BC (2021) has unsettled the province’s regulatory landscape. Through a collaborative redesign of the permitting process by the BC Energy Regulator and Treaty 8 First Nations, a new process is being put to the work of undoing entrenched settler colonial entitlements in the permitting process and to prevent the impacts of cumulative effects. Starting with a moose and its wallow, the paper explores the impact of the case for regulators and for proponents with mineral tenure in the prolific Montney formation that underlies the traditional territories of BC Treaty 8 First Nations.