For decades, the fossilized skulls and teeth of Paranthropus robustus have provided a glimpse into the life of this extinct hominin, which roamed the landscapes of what is now South Africa nearly 2 million years ago. Its massive jaws and heavily enameled teeth suggest a diet tough enough to withstand lean seasons, while the differences in skull size hint at a polygynous mating system, where larger males likely dominated smaller females.

Yet for all that is known about its chewing power and social structure, far less has been understood about how Paranthropus robustus moved through its environment. While the species is often assumed to have been a habitual biped like modern humans, postcranial fossils have been scarce.

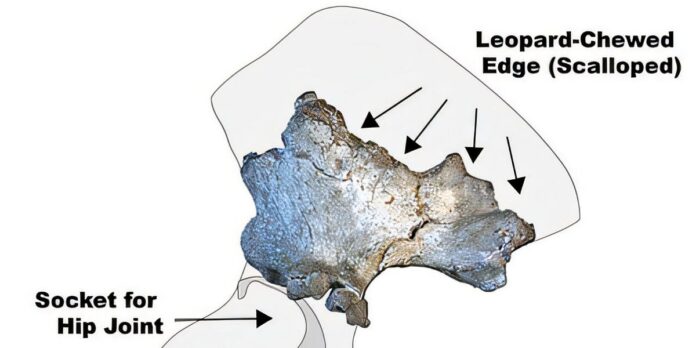

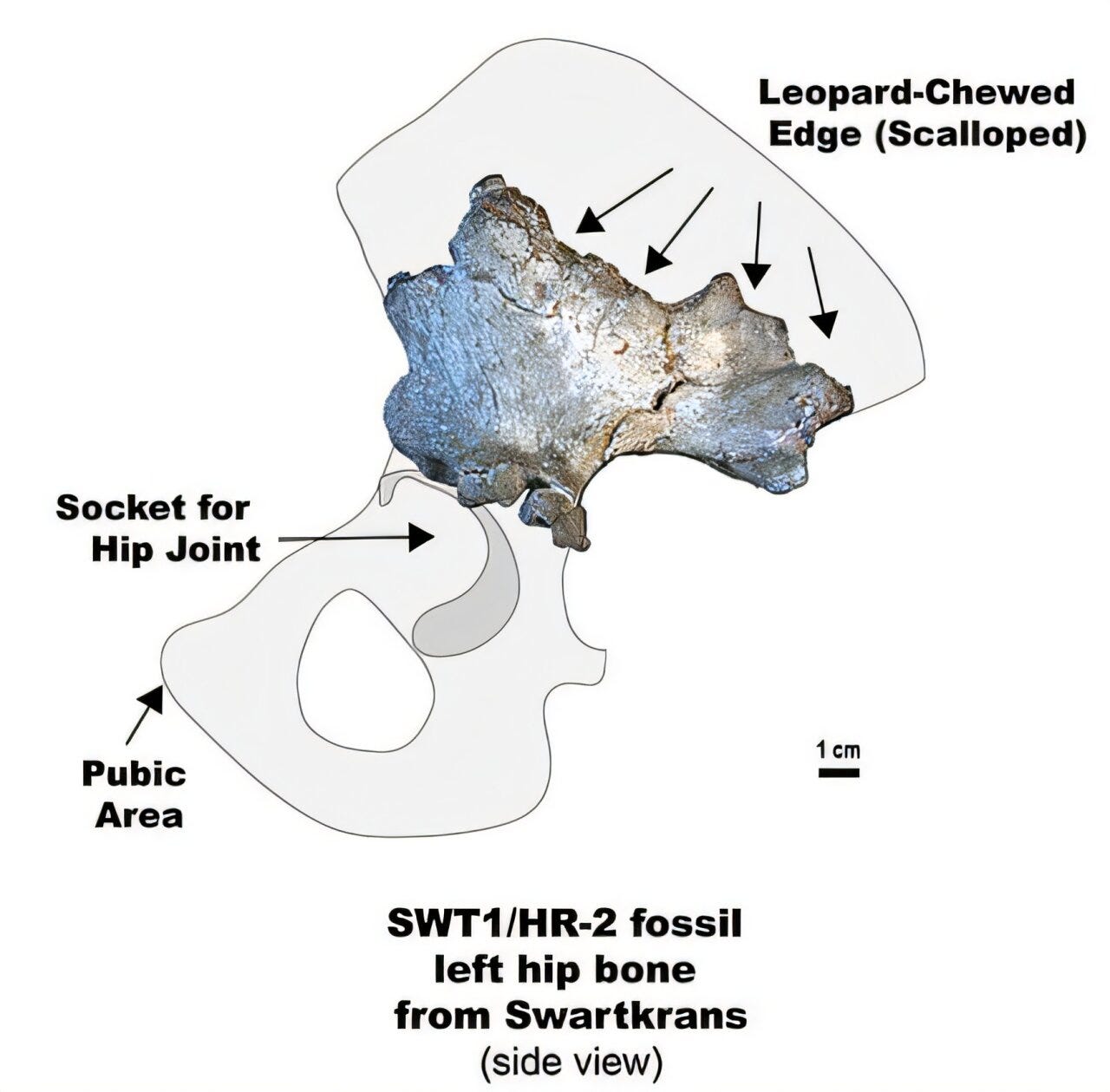

A new discovery from Swartkrans Cave—a site long known for its wealth of Paranthropus robustus fossils—changes that. In a recent study published in the Journal of Human Evolution, researchers describe the first set of hip, thigh, and shin bones found in articulation, meaning they belonged to a single individual. This rare find confirms that Paranthropus robustus was an upright walker, just like Homo sapiens—but it also reveals something unexpected: this particular individual was remarkably small.