Michel Gondry has had a long relationship with animation, but he has never quite made a film like this one.

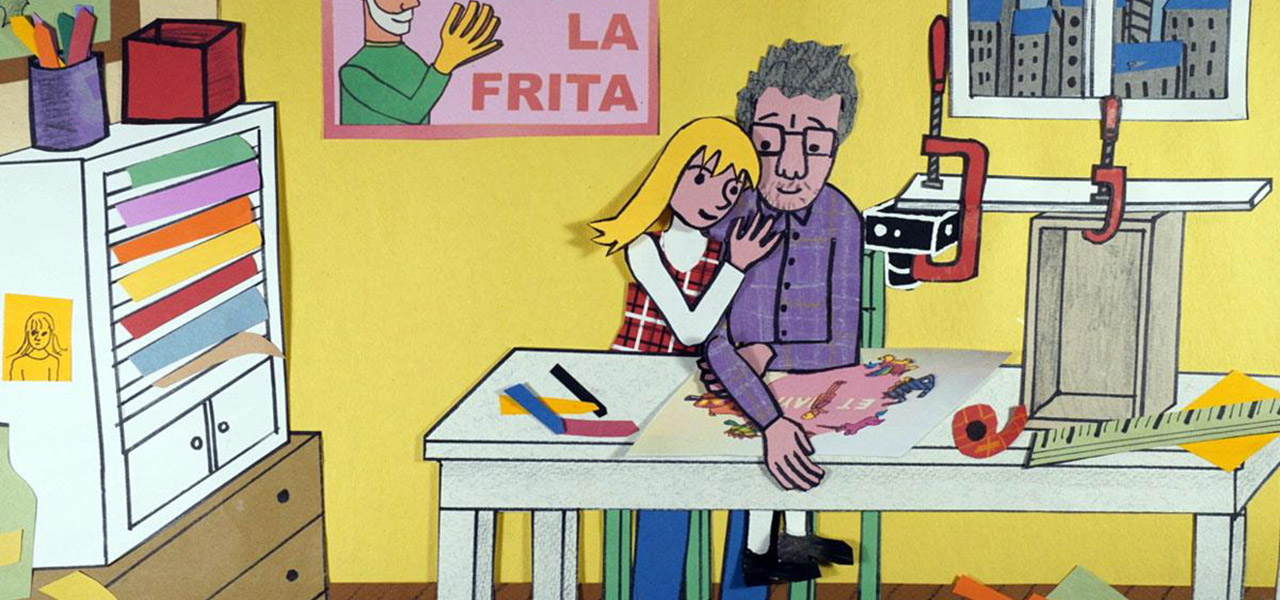

Released last October in France, before premiering internationally at the Berlinale last month and winning an award, Maya, Give Me A Title is a 61-minute compilation of shorts plus wraparound material that Gondry made for his young daughter over a period of six years. Based on prompts from his daughter, and made as a way to remain connected to her even while he lived in another country, the film radiates Gondry’s love for his daughter and her imagination.

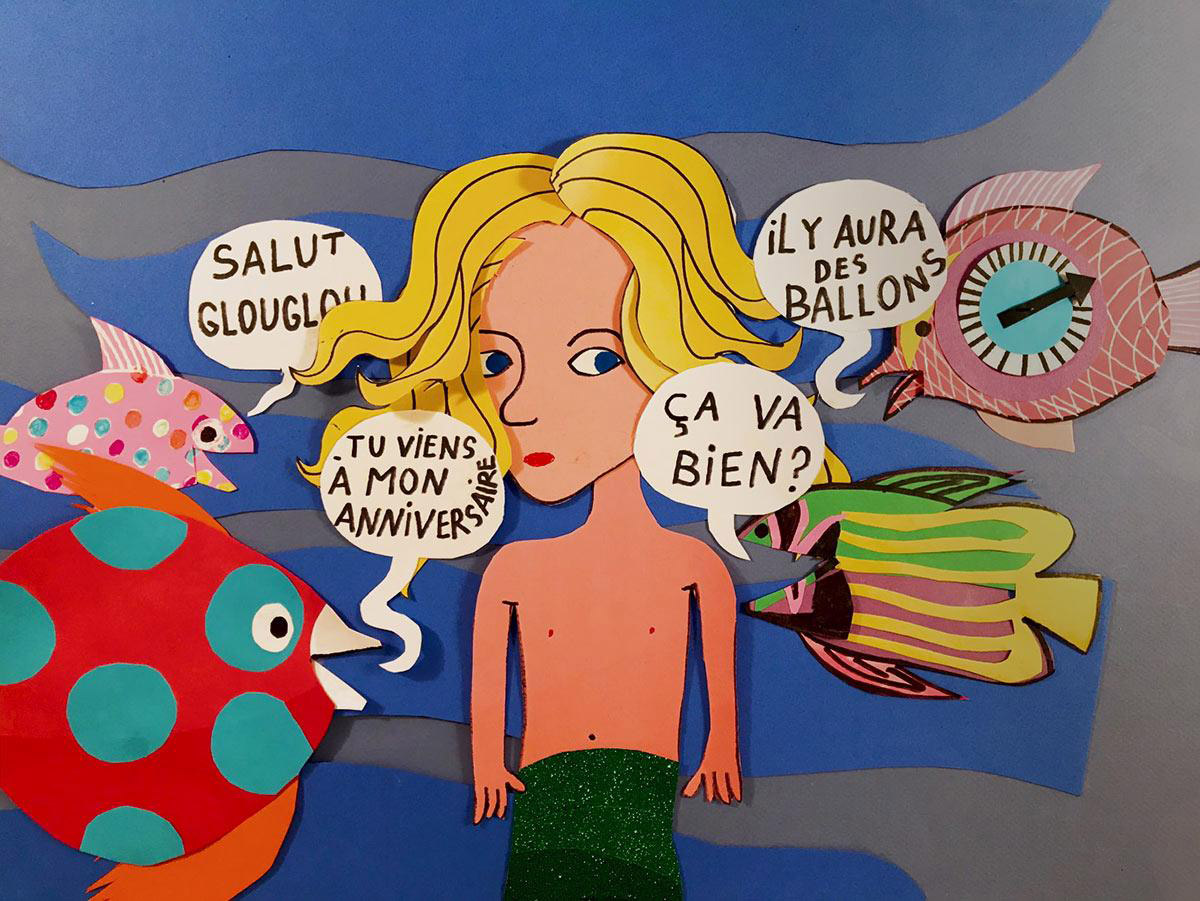

The animation technique, a lo-fi mix of stop-motion and paper cut-out animation brought to life by Gondry himself, is a wonderful journey into the path of a creative artist learning to communicate through a medium he discovers along the way. As such, Maya, Give Me A Title is a witty, funny and whimsical feature, where children and parents alike will travel within Gondry’s mixed-media universe, constantly wandering back and forth between volcanoes, apartments, lush seas and impressive paper settings.

Cartoon Brew spoke with Michel Gondry to learn more about the making of this singular animated film. Maya recently had its North American debut at the New York International Children’s Film Festival, and it will screen this June at the Annecy animation festival, where Gondry will receive a lifetime achievement award.

Cartoon Brew: What is animation to you, as a filmmaker and an artist?

Michel Gondry: It’s quite simple. To me, animation is a discovery of cinema 24 times per second. You start over each time, and that’s why animation has this glow, this vibration. Every second, every frame is a new film, a new discovery.

When did the idea of animated films for Maya begin?

I started with a small animated film for her third birthday. Then, I’d ask her for a title, and she’d see the result sometime later. I integrated characters from her daily life: her grandparents, her cat, her mom. By the time I was done with the process, I had made roughly sixty shorts. I created films that allowed her everyday life to drift into fantasy, not unlike a bedtime story: her mom would read her the titles and dialogue, then give me feedback on Maya’s reactions. What she liked, what was a bit scary…

It was only a year after I was finished with the process that I thought about turning it into a film and sharing it with others, as a way to express the relationship between a dad and his daughter through animation.

Can you tell us more about your influences, or the animation artists that have shaped your relationship with animation?

I would not say influenced, it’s more like they stimulated me. They’ve shown me that you can have complex ideas and a complex story with very simple graphics. I remember one particularly, I think it was a Russian cartoon, very didactic, about somebody who killed a person because they made too much noise. And it’s very simple, there’s a lot of fixed frames, and that’s all there is to it.

When I do animation, I just try to tell the story and I try to make the characters do fun stuff, and then I find ways to make them work in a very simple way. There are enough contingencies in animation to avoid creating extra complexity, so there is no specific aesthetic research except that I like to put paper that looks nice together. There is simplification for the background. They’re technical, but they also give a specific look to the film.

Talking about technique, how did you make these films? Because the evolution of the process is palpable throughout the movie.

Yes. As Maya grew up, I had to bring more sophistication to the story and the look of the animation. I always started with a storyboard, and with the backgrounds I created, which I often reused throughout the films.

For the backgrounds, I use a big piece of paper, and I try to make them quite simple. But sometimes, they take a long time because there are lots of elements moving in the scene. If I shoot inside a factory, I want to see cogs in the background, lots of pipes, and those details give life but also impact the shot. Sometimes, it can be part of a table, a plug, or a shoe. When I cut each element, I decide which parts will be moving.

Then I put my camera above it with a rudimentary wooden system and I record a frame per motion, moving elements by half-centimeter or a centimeter. Those movements have to be very small so it doesn’t jump around too much. After that, it’s just a regular editing process.

What’s an overlooked aspect of the film that you’re keen to talk about?

I rarely get to talk about the letters, but they play a very important role in each segment. Not only did they have to be there, but they were also part of the text written for Maya’s mother to read. So as soon as they appear on screen, I looked for ways to make them physically present and entertaining. I put myself under great pressure to cut out those letters and bring them to life, and it’s one of the aspects of the film where you can see the imperfections, but also the playfulness of the medium.

With this approach, your work indeed celebrates both craftsmanship and imperfection.

It’s not really that I celebrate it; it’s more about accepting these imperfections as part of the process. Because I couldn’t possibly tell a full story in three weeks if I had to reach perfection, like most animated films. So, I accept it, and I hope that the audience will do too. As long as we get the story, and a little motion. And sometimes, I elaborate more, I add motion and details. But most of the time, it’s all made to tell the story, and I think it’s maybe also why people are more forgiving of the imperfections. Because they still see something that a father did for his daughter.

How did you choose the films that would be included in this feature?

From the beginning, there was always one that I showed to my friends to talk about this idea. So I wanted to include it in the film. There are some that I prefer, and then I alternated with some simple and complicated ones. It’s not much more than that.

But I already know which films will be included in the second iteration. The first version of the film was too long, and that’s why we decided to split the film in two. The films that make the second feature are more varied, more experimental. So I’m very excited to put them out there later this year.

Can you share some of the challenges that you encountered during this project?

Well, for instance, the giant robot was a big deal because there was a lot of movement involved between the arms, legs, and body. This film was overall a great challenge, to manage all the “troopies” jumping, the fake cops arresting the other fake cops, after being themselves arrested by the first fake cops; sometimes I felt like I would never be able to do that, but in the end I always found a solution.

Animation is often a team effort, how did you feel animating these films on your own?

It felt great. I had set a rule before the start of this endeavor: I would not redo a shot, except if it was terrible. Because it’s so much work already. I also had help from time to time, for the cutting process, but mostly that was it. In a way, I think I wanted a certain level of authenticity. I was the only one working on this project, and this was my effort.

How did you integrate sound in the films, and were you already thinking about a soundtrack while animating?

When I was done with a film, I would go to the internet and dig out any type of sound I could find. Then my assistant would edit them. But when we moved to a feature film that would be commercially released, we of course had to replace sounds in order to make the film legal. But the sounds were already there, so it was all about replicating and finding the right match.

How do you feel about sharing this film with international audiences?

I really enjoyed creating those films. Especially because I sleep very poorly and so I could get up in the middle of the night and animate for three or four hours straight while listening to audiobooks, especially Russian novels. It was a great experience, and it’s really exciting when you have a storyboard and you figure out how you’re going to execute it and bring it to screen.

What I’m grateful for is that I rarely get feedback criticizing the unpolished finishing of the film, because people read it as I meant it, the communication between a father and daughter.

How do you feel about animation today, in the midst of its recent struggles?

One thing is that it definitely isn’t like other big productions released internationally nowadays. To me, the film looks handmade, obviously. But I think it’s inviting in that way, as it shows that you can be entertaining with simple skills and simple animation.

I’ve been asked a lot about my stance on AI, and to be fair I don’t have much of an opinion about it. There are some elements and techniques in animation that are very expensive, such as rotoscoping, and finding ways to work around it might be interesting. But to me, the main problem is about what lies behind technology for our society as a whole.