The maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) market is experiencing significant supply-demand tensions.

The vigorous post-pandemic travel recovery has led airlines to increase fleet utilization, extend the life of their older aircraft and even reactivate some airframes that had long been in storage.

This has coincided with a number of quality production issues which have been plaguing several major engine makers, resulting in numerous unplanned aircraft groundings and longer lead times for the supply of new engines.

Add to this the fact that supply chains for many key parts and components are strained, almost to breaking point, and the result is a perfect storm of problems that has impacted airlines across the board.

However, with big challenges often come great opportunities and, in this context, some operators have been able to boost their in-house MRO arms and develop them as significant stand-alone business units.

This is the case with Spanish flag carrier Iberia, part of the International Airlines Group (IAG), which has been betting on the growth of its MRO subsidiary, Iberia Maintenance.

Addressing the media during the presentation of the first Airbus A321XLR, which entered service with the Spanish airline in November 2024, Iberia’s CEO, Marco Sansavini explained that the carrier’s MRO unit would be one of the company’s vectors for growth in the years to come.

So, intrigued by this remarkable statement, AeroTime traveled to Madrid to visit La Muñoza, a vast sprawling complex next to Madrid-Barajas International Airport (MAD), in February 2025 for an exclusive look at Iberia Maintenance’s MRO business.

Covering all bases

Iberia Maintenance’s MRO services are structured across four major business areas, the largest of which is engine maintenance, representing 85% of revenue, as of early 2025.

This is followed by the heavy aircraft maintenance business, the repair and overhaul of aircraft components, and a training division. All four areas are currently going through a period of unmitigated growth, constrained only by the limits imposed by physical infrastructure and the requirements of recruiting, and training a highly skilled workforce.

In this context, the engine shop plays a particularly relevant role in Iberia’s ambitions in the MRO space. The Spanish airline, which is already a major player in the European narrowbody engine market, aims to further consolidate and expand its position on the global stage.

The Madrid facility is the largest service center for narrowbody aircraft engines within the IAG Group (British Airways had another facility in Cardiff, Wales, which was sold to GE in 2018), but intra-group work only accounts for around 20% of its workload, the rest being for third party customers. For some engine types, external customers represent almost the entirety of the assignments.

Iberia Maintenance’s MRO capabilities include four different engines, all of which are to power narrowbody aircraft and represent different stages in the evolution of engine technology. One of these, the RB211-535, is on its way out since many of the Boeing 757s they equip are being progressively retired.

The CFM56 and V2500, which are also serviced at La Muñoza, can also be considered legacy types, although they still equip thousands of A320ceo family and B737NG aircraft worldwide.

And, finally, in October 2024, Iberia Maintenance added the new GTF engines made by Pratt & Whitney to its portfolio. This includes the PW1100G-JM which powers the best-selling A320neo family aircraft.

GTF engines are, of course, seen as an avenue towards future growth, but Iberia Maintenance’s MRO management is not dismissive of the size of the market that older engine types represent.

“Lots of engine shops specialize in servicing only the newest types of engines but we, at Iberia, want to support the full cycle,” explained Julián López, Chief Commercial Officer at Iberia Maintenance during AeroTime’s visit to La Muñoza.

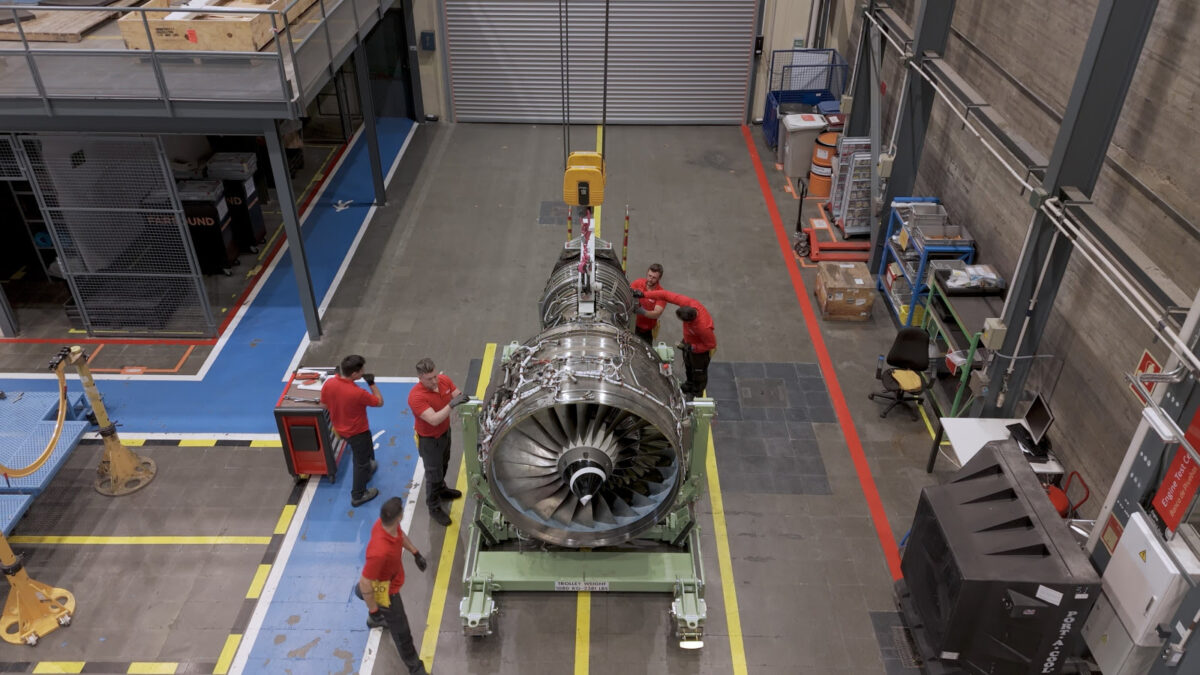

Approximately 400 people work at Iberia’s engine shop, with all processes housed in a single building. At the time of AeroTime’s visit there were 82 engines undergoing some sort of maintenance process.

All engines follow the same process when they arrive at La Muñoza. The process starts with disassembling the engine and assessing its condition. Despite there always being an initial scope of work, it is not unusual for other issues to be detected upon inspection and need to be addressed.

This is a critical part of the process, since the capacity of Iberia’s engine shop is limited to 215 slots per year and every engine takes precious space and resources. Everything must be accurately planned to make sure resources are used in the most efficient way and prevent unnecessary delays.

Engine servicing is a rather laborious process. Once the engine has been disassembled, it must go through a verification phase in which it is necessary to assess whether the parts in question can be repaired or not. Technicians are able to identify and track these parts through their color tags.

Iberia has the capacity to repair many of the parts on-site. However, when they are considered beyond repair, they must be replaced. This is one of the steps in which the current strain on supply chains can be felt most acutely. The fact that Iberia keeps a significant number of parts and components stocked on-site in a large vertical warehouse adjacent to the shop helps the process run more smoothly.

“It will take [a] minimum [of]18 months to solve the capacity constraints in the industry, which are caused by supply chain and produce bottlenecks,” said López.

He also explained that, as of early 2025, the typical amount of time an engine spends at the shop is 100 days.

In any case, parts and components must undergo a final verification phase, which includes what is called “non-destructive testing” in a lab before the engine is reassembled again.

Reassembly is a complex process that takes place in two stages. The first is modular assembly, which is exactly what this name implies. Different sections of the engine are reassembled separately before being joined together during the second and final assembly stage.

At any one time there are usually four to five engines in the final assembly stage. This part of the engine shop never stops. It works around the clock, with staff working three shifts.

But this is not the end of the process. Once the engine has been fully assembled, it is time for it to be tested in conditions that mimic those inflight. This is done on the ground, in a special chamber next to the engine shop. There, enclosed by high concrete walls, the engine is fired as if in a routine flight, while technicians monitor every relevant metric through sensors.

These engine tests can go on for hours at a time, consuming a sizable amount of jet fuel. This is why Iberia has selected this activity for one of its first uses of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) at scale, used in blends of up to 10%.

Walking the shop floor

Engine testing can be said to represent the narrowest bottleneck in the engine shop operation, since only one engine can be tested at any one time.

However, these constraints are not felt in the parts and components repair business, which is also firing on all cylinders.

Supply chain constraints have represented a boon for firms able to keep airlines supplied with all sorts of components. In 2024 this business unit expanded its workforce by around 30%, to 250 people, and in 2025 it expects to increase it again by 15%. Unlike the engine shop that works mostly for external customers, here 75% of the work is for airlines of IAG.

To put things in context, Iberia Maintenance handled around 28,000 components in 2024 representing more than 4,000 different product references.

The assortment is truly diverse and a walk through the aisles of the parts and components facility feels like visiting an enormous aerospace flea market. From right to left you can find workshops covering a seemingly endless range of items you normally find onboard aircraft, from tires and nacelles, to seats, galleys, and engine accessories.

One of the latest capabilities to be added to the list is the maintenance of wheels and brakes for the A321XLR, Airbus’ latest aircraft type, of which Iberia became the launch customer in November 2024.

Wheels are actually a good example to illustrate the scope of this operation, since it is a part of the aircraft that constantly wears down. More than 9,700 wheels are used by Iberia and Vueling, IAG’s low-cost carrier, per day. So, Iberia Maintenance sends two trucks to Barcelona each day to keep Vueling’s fleet supplied with wheels for its A320 family fleet.

Our visit concluded at Hangar 6, one of the largest facilities at La Muñoza and where heavy base maintenance, the thorough C and D checks all aircraft go through every certain number of years, is performed. Capable of holding up to 12 A320s or eight widebody aircraft simultaneously, Hangar 6 holds several world records due to its dimensions.

When it was built in the 1990s, Iberia’s Hangar 6 was one of the largest diaphanous structures in Europe and also boasts one of the largest suspended roofs (it has since been surpassed by other structures such as the O2, formerly known as the Millenium Dome, in London, UK). The entire roof, weighing approximately 4,000 tons, is suspended by a large arch, which keeps it in place.

As massive as its facilities may be, all of Iberia’s managers AeroTime spoke with during the visit highlighted something much more difficult to measure: the know-how developed over many decades in the business. Iberia Maintenance can trace its roots back 90 years to the early days of the airline.

It is not a coincidence that the fourth arm of Iberia Maintenance’s MRO business is training. It takes between six and 26 months to train the different profiles of qualified staff required by the MRO business.

In this regard, and even if the firm offers its training services to the market, its growing order book and the current conditions in the global MRO market are certain to keep its internal training program busy for quite a few years.