The Belgian history of animation is filled with delightful shorts, memorable features, and forgotten treasures. Jean-Paul Walravens, better known as Picha, may well be one of these most important Belgian animation directors, yet little of his work is still known to younger generations, locally or internationally.

Picha, 82, started working as a cartoonist in the 1960s and acquired international fame for his works in French satirical magazine Hara-Kiri and American publications such as National Lampoon and The New York Times.

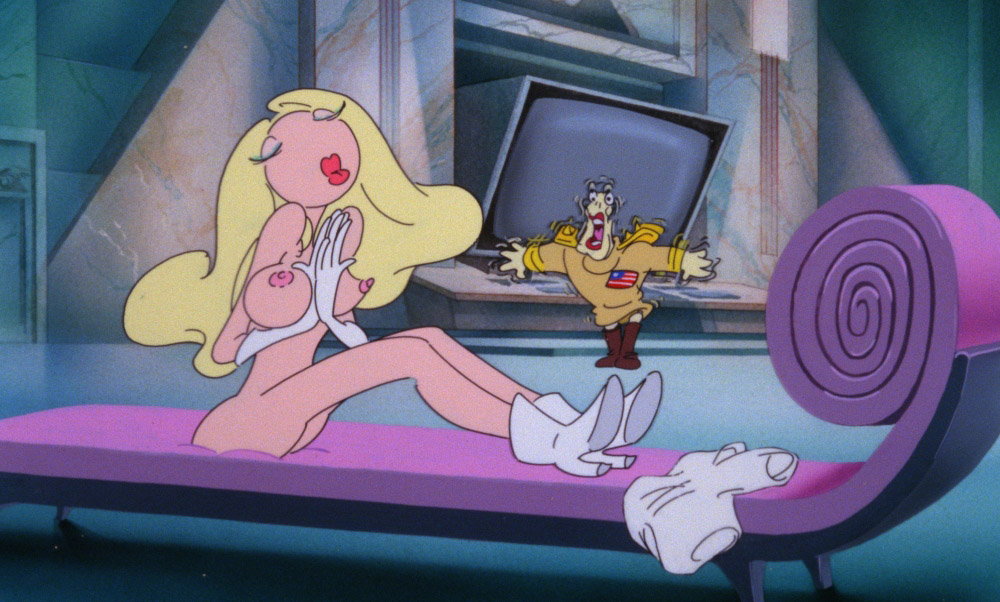

In the 1970s, he turned filmmaker, bringing satire and adult animation to the big screen with the infamous feature Tarzoon: Shame of the Jungle (1975). His second feature, The Missing Link (1980) brought him to the Cannes Film Festival, while his third film The Big Bang (1987) was released throughout Europe.

Picha continued working on animation projects in the Nineties, including works for younger audiences, like Zoo Olympics. In 2007, he finally managed to finish one of his long-gestating features, Snow White: The Sequel, but in the post-Shrek era, his satirical take on fairy tales felt behind the times and it bombed.

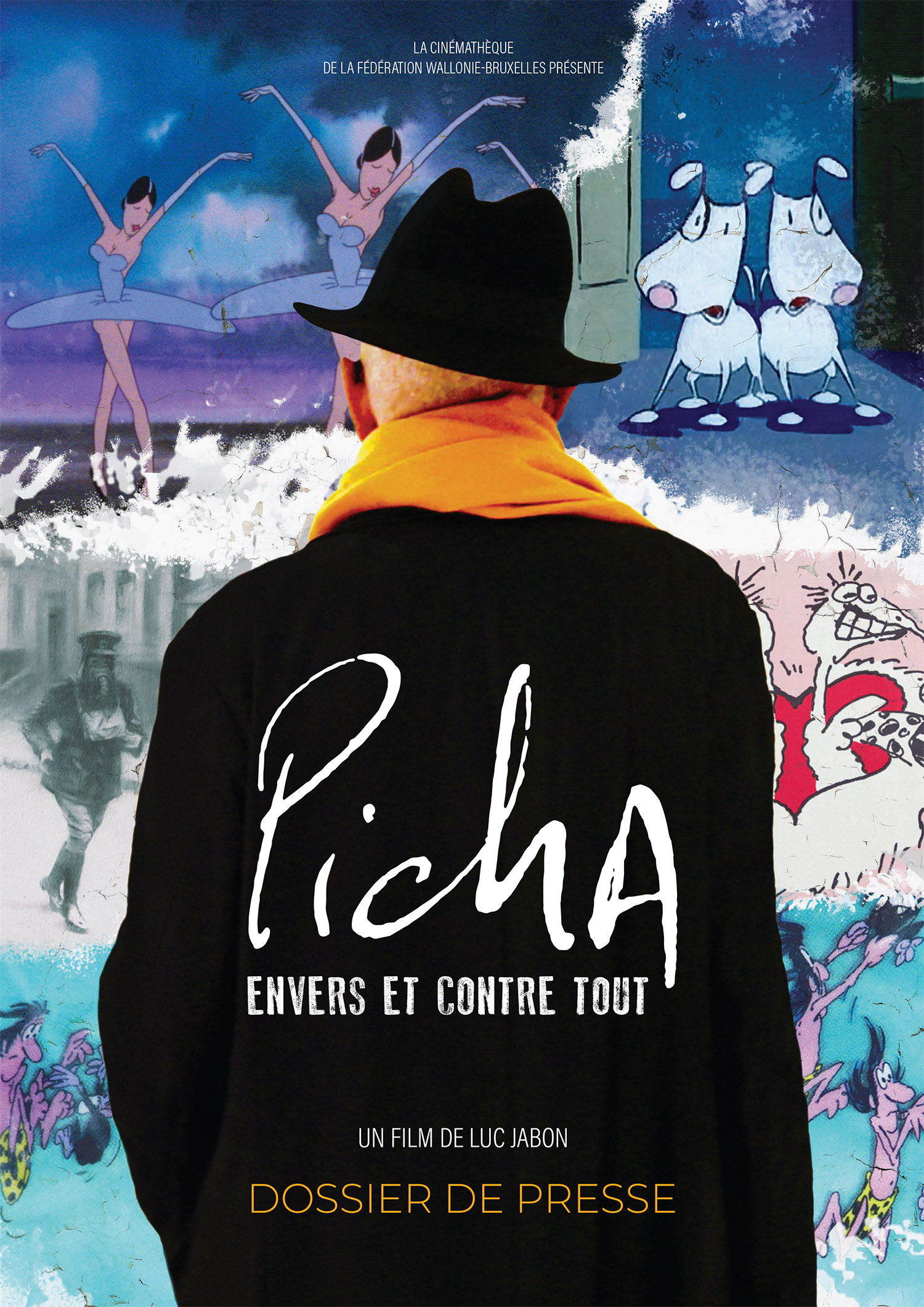

Afterwards, he left animation for good and turned to painting, and his work was slowly forgotten, remembered only by animation historians and satire buffs. Now, a new documentary, Picha Against All Odds, produced by the French-Speaking Cinemathèque de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles and directed by Belgian filmmaker Luc Jabon, unearths Picha’s legacy and recontextualizes the work of this European pioneer of adult animation.

Ahead of the documentary’s world premiere at the Anima festival in Brussels, Cartoon Brew sat down with the film’s director to learn more about the documentary.

Cartoon Brew: Why a documentary on Picha today?

Luc Jabon: Initially, this project came from a request from the Cinémathèque de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles which for several years has released a certain number of portraits of filmmakers seen by filmmakers. At one point the question arose of making a film around animation and its past. It is within this context that the figure of Picha emerged. So to me, it wasn’t a deliberate choice, but upon meeting Picha, I was struck by his journey as an artist, and what he experienced during his decades-spanning career. And that’s where my desire to tell something about this somewhat unusual artistic journey was born. It was only as the film progressed that I fully felt the relevance of the questions that satire and pastiche posed yesterday and still pose today.

In 2006, Picha was the subject of another documentary, My Uncle from America is Belgian. How does your film fit alongside that one?

My Uncle from America is Belgian, a film by Eric Figon and Françoise Walravens [Picha’s niece], is a rather intimate portrait of Picha. It’s a very beautiful film, quite impressionistic, which had already done this work of portraying the man behind the artist. What interested me instead was to create a narrative based on Picha’s works and the movements of his career, and so that is how I modeled my filmmaking approach.

Were you already familiar with Picha’s work when you started working on the project?

I knew it from having discovered his films at the time they were released. Because even if he is a little older than me, we are practically from the same generation. I therefore experienced these works at the time when his films thunderously entered the galaxy of animated features, which was quite normative at the time, and which he completely transgressed with the means at his hand.

After this period, I admit to having lost sight of Picha, and it was only in this documentary process that I discovered all the aspects of his work, and in particular his recent painting career, which is fascinating to me and mirrors a lot of the themes depicted in his previous works.

How did Picha’s films impact you at the time?

As I said, and as several people in the film remind us, we must not forget that we lived in a very normative world. And it’s this generation of late 1960s artists that really decided to ruffle society’s feathers. In a very static decade, publications such as French satirical magazine Hara-Kiri, where Picha started his drawing career with many other big names, were a God’s gift. The perfect way to shake up the lines of a very frozen post-war society.

How did you choose the people you interviewed for your documentary?

It’s kind of a constellation, that is to say I found one which led me to the other, and so on. But what was particularly important to me was making the link between past and present.

I didn’t want to make a nostalgic portrait of Picha, and something that struck me from the start of the project was that Picha is completely forgotten today. The new generation of animation filmmakers does not know of him and his films, and that raised questions for me.

This is why in the film, we talk a lot about the state of animation at the time, to understand how Picha is so disruptive compared to the general state of animation in Belgium, in an era where animated features came mostly from Disney, and in Belgium from Belvision with comic book characters such as Tintin, Lucky Luke, or even The Smurfs.

But at the same time, I wanted to have people capable of talking about animation today, and not only animation but also the question of irreverence and transgression. That’s why Belgian cartoonists and artists are also present in the film, both colleagues who knew and worked Picha, and also people who were inspired by him.

In the film, you also draw a parallel between Picha and American filmmaker Ralph Bakshi, who boasted similar irreverence with films such as Fritz the Cat and Coonskin. How does Picha fit into this international landscape of 1970s emerging adult animation?

Before being a filmmaker Picha’s first career was that of an extremely well-known cartoonist. It’s a part of his life that has been completely forgotten today, but he was one of the greatest Belgian satirical cartoonists of his time. He worked for Hara-Kiri, but also for other Belgian newspapers including Special and Pourquoi Pas. He also worked internationally for National Lampoon and even The New York Times. So when Picha turned his pen to animated cinema, he didn’t start from scratch.

And that’s also what interested me about him, this ability to move from one artistic path to another, which is quite rare. Artists are very quickly labeled, they enter a category and stay there all our lives. Picha always refused this, he went from satirical drawing to animated cinema, then moved on to television, before turning to painting a decade later.

Would you say it’s only a result of his own will, or an evolution of society that pushed him into these new pursuits?

Both, of course. Picha also had to adapt to the different situations in which he found himself throughout the times. You should know that between his last two animated films, twenty years passed, so everything became more complicated for him. Especially since “his” animated cinema, the one he employed on Shame Of The Jungle in 1975, and his other 1980s features, was no longer the same at all.

Diving into this history is also a look back on a bygone era of animation…

It’s something that I definitely wanted to show in this film. Today, as we look at cg animated features, or even drawn animation, the audience doesn’t necessarily know how these films were made back in that time. All these aspects of 2d animation, such as celluloid workers, and all the little hands that had to create in-betweens to create movement, its something wonderful to see. I’m very grateful to the Cinémathèque for having unearthed the archives that you see in the documentary, and for Claire Gobert, one of Picha’s colleagues, for sharing her experience and her memories of that time.

When Picha started working on his independent features, Belvision was employing sixty to eighty people on their features, so it’s also interesting to shed light on the difficulties that Picha encountered during his own films, without the backup of such a studio. I was very happy to be able to share these glances in the past, retelling a story of Belgian animated cinema that shaped what Belgian animation is today. Directors such as Patar & Aubier (A Town Called Panic) or producer Vincent Tavier [who recently co-produced Claude Barras new feature Savages] were all very influenced by Picha’s films.

What do you think connects these very different yet intricate artistic paths?

The love for the image, to begin with. But beyond the image, there is something deeper, a way of drawing a sharp look at the world and what surrounds us. Even when, in the 1990s, he made television dramas aimed at young audiences, there is always a little something in Picha’s series that stands out, that deviates from the norm. As a documentarist who also tries to go beyond simply sharing someone’s life on screen, this particularly appealed to me.

How can one show Picha’s films today? Is it even possible, interesting, and in what context according to you?

This is also one of the main questions the documentary asks. As far as I am concerned, I agree with the point of view of several speakers in the film, we must continue to show everything – as long as it is of quality of course – but it is absolutely necessary to contextualize these works.

It is essential to understand why, how, and in what conditions they were made.

Because the perception of satire, transgression, and humor have completely changed. Frédéric Jannin and Pierre Kroll, both Belgian cartoonists still operating today, tell it very well.And that’s why I also wanted to create a meeting within this film, between today’s animation film students and Picha. And I had this opportunity, and I want to thank Picha for taking part because it was a difficult and powerful encounter for him, with a very virulent look at the way in which these students see his cinema today. And the fact that they were able to express this opinion, to question these films as well as the filmmaker, and that he was able to respond, I find it super interesting.

It weaves this link between past and present that I hold dear, and that is key in this film. We live in what I sometimes call the “tyranny” of the present, but documentaries are a form that allows us to go back and confront this vision. While at the same time benefiting from the “luck” of reality, because this meeting was absolutely not scripted!

And the discussion that arose there was very interesting. These directors are the animation filmmakers of our future. And while talking about animated cinema today, they are also questioning the animation of yesterday while creating the world of tomorrow.

Picha Against All Odds premiered at the Anima Festival on Monday, March 3rd. In March, as part of the Offscreen festival in Brussels, seven films by Picha and his contemporary and co-author Boris Szulzinger – recently restored by Cinematek – will be presented this month in Belgian theaters.