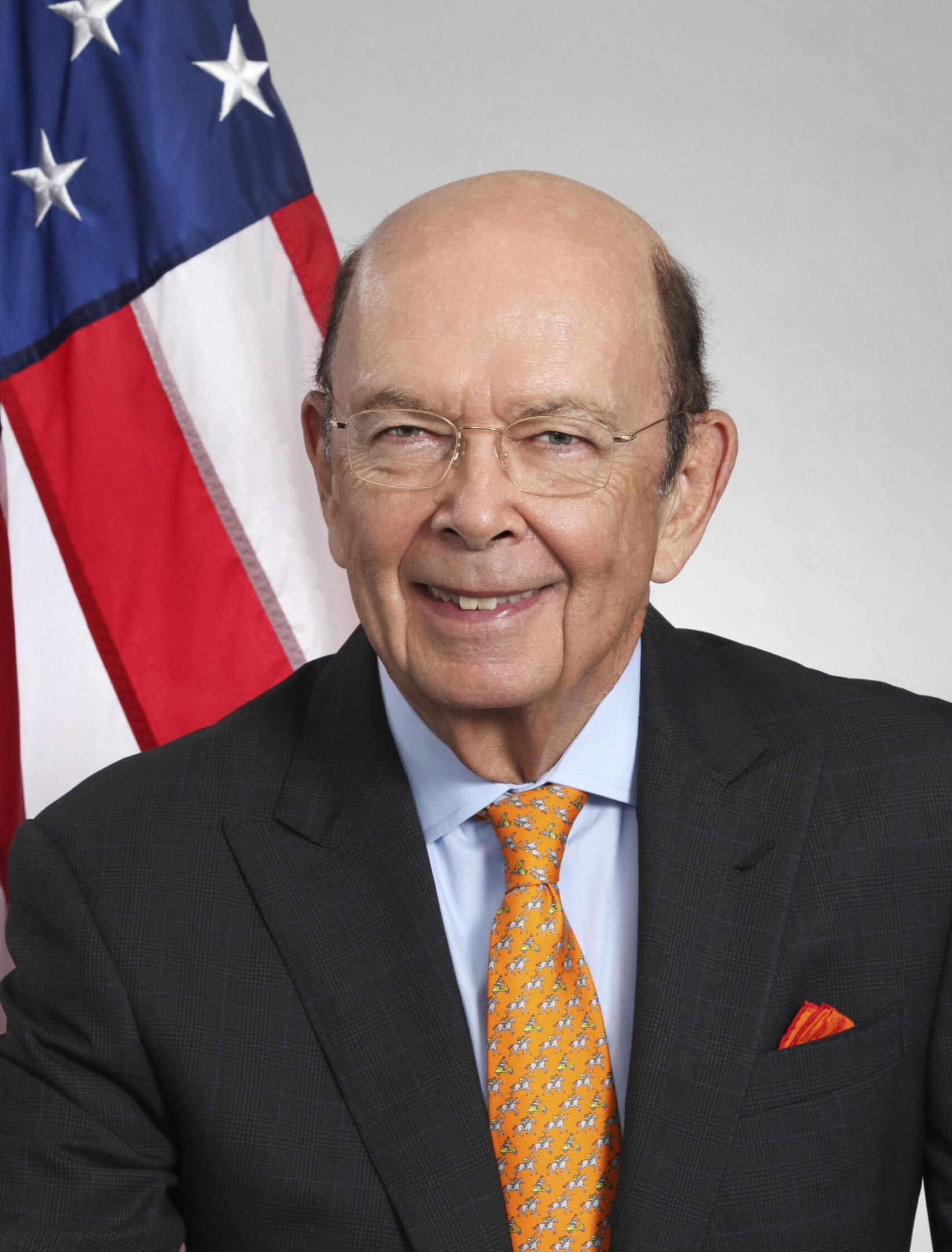

Global Finance: Do you see a significant difference in how the second Trump administration approaches tariffs, compared to its first term, when you were Secretary of Commerce?

Wilbur Ross: The biggest difference is that we were charting uncharted waters in the first term. Namely, nobody really knew if [President Trump] had the statutory authority to put in steel tariffs, aluminum tariffs, refrigerator tariffs, or washing machine tariffs. So, we dredged up old legislation, some from 1976 and some from 1972, which were tested in court and upheld by and large.

The first thing was that it took a lot of time in the first administration to ensure we had the power to do some of the things he wanted. Now that that’s been established and he was happy with the results, the President is using tariffs much more broadly. He’s using them as a revenue measure, a diplomatic measure, and for all sorts of other purposes, such as trying to control fentanyl smuggling and controlling the border. That’s the first difference.

The second difference is that he has much more public support in general and with the Republican Party. The last time around, he was much more controversial at inauguration than this time. You saw that in the popular vote. But even more importantly, last time around, he had relatively little control over the Republican Party. There were a lot of free traders still in, particularly the Senate among the Republicans. Most of them have now retired. So that’s a big difference. And you’ve seen his ability to control the Congress in some of the notions he’s been able to force through this time, now by very skinny votes. Still, essentially this time the Republican Party in the Congress is pretty well unified behind the Trump agenda. They were not the first time.

And the last factor that’s different is back when he was in his first term, there was still the global perception that free trade was the big objective, and the business community still was very much of the view for more internationalization, more globalization of supply chains. Now, particularly because of COVID-19, there’s a rethinking of that. At this point, many business executives recognize that every time they add another country to their supply chain, they’re adding a point of vulnerability.

There was the beginning of a shift from globalization to localization, making factories closer to their consuming markets. That was coming even independently of Trump.

GF: Do you feel the administration has an overarching plan for tariff implementation, or is it being far more reactive to the situation? What did President Trump not get from the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) that he wants now?

Ross: Oh, well, that’s a very good question. To answer this, we need to look at the two parts of USMCA. As you know, Mexico has been a huge beneficiary of our moves against Chinese exports to the US. Because the peso has been struggling as a currency and Mexican wage rates haven’t increased much, they are quite competitive with China when you factor in shorter shipping distances, lower in-progress inventory costs, and reduced transportation expenses.

However, Mexico hasn’t really lived up to the free trade agreement we made with them. It has not liberalized its oil and gas sector as it was supposed to, and it hasn’t made its courts more impartial—an important component of the deal. Third, with the rise of electric vehicles and digital manufacturing moving to Mexico, we need to modify the rules of origin somewhat.

I want to add that I’m not a part of the administration (now), nor am I their spokesperson. These are my personal opinions.

So, you’ll remember that under USMCA, 60%–70% of the content had to come from countries with a wage rate above $15 an hour. That rule was meant to ensure that the benefits of trade shifting to Mexico would be shared between Mexico and the U.S. Now that the types of products moving there have changed, we need to refine the rules of origin accordingly. So, those adjustments were needed anyway when it comes to Mexico.

What’s new is the fentanyl issue. Trump has been pressing Mexico on fentanyl and border security for a long time. But if you recall, during his first administration, he got Mexico to deploy 20,000 troops to the border by threatening tariffs. So that strategy isn’t new—he’s just actually implementing it this time.

In terms of Canada, things are a little different. Until now, he hadn’t needed to push Canada on fentanyl and border security. The Canadians made a big mistake in how Prime Minister Justin Trudeau responded. Trudeau’s initial reaction was, “Well, it isn’t that big a problem. It’s only a few kilos of fentanyl.”

Two kilos of fentanyl coming in from Canada can kill a lot of people. Second, we believe that as Mexico cracks down on cartels, those operations may shift to Canada. That’s why we want Canada to be prepared to address the issue.

I want to add, that I am not part of the administration (now), nor am I their spokesperson. These are my personal opinions.

Similarly, Trump had been pressing Canada on dairy products and softwood lumber since his first term. But for the first time, he’s decided to take a step further on softwood lumber by opening up the U.S. Forest Reserve. We have plenty of milling capacity for home building and other purposes, but the supply of stumpage (harvestable timber) has been somewhat limited. Now, that restriction is being lifted. That structural change led him to conclude that Canada’s share of softwood exports should be reduced. So, the factual situation has changed, and his response to it has evolved accordingly.

GF: What lessons did you learn from President Trump’s negotiation style when first negotiating the USMCA? To remove some of the tariffs, he’s asking for the end fentanyl smuggling, cessation of illegal immigration and Canada to become the 51st state. How much of this is negotiation and how much is trolling?

Ross: I met President Trump by representing his creditors in the Trump Taj Mahal. I was in a very adversarial position against him. His style is very aggressive and very strong in negotiations. You see that coming through in the trade. It wasn’t quite as aggressive last time, partly because he has done a lot of business, including some real estate development in foreign countries.

Last time, he was not an expert in the more intricate aspects of trade. He’s learned a lot from the interactions that we have had with other governments then and now.

His style of negotiating is one of pushing for things very, very hard and being willing to take punitive action if he doesn’t get what he wants. You saw that with Ukraine.

With Panama, he was able to create an environment where all of a sudden, Hutchison Whampoa, turned over control of not just the two key Panamanian ports, but many other ports that it was operating. He would never have thought through that level of detail in Trump 1.0. Now he knows more about potential targets. And every time he succeeds, like with the Panama Canal, which as you remember, didn’t get that much press because it was accomplished without much hooting and hollering. Hutchison made a very good commercial decision to sell those ports to a syndicate organized by BlackRock.

One way of responding to Trump’s new policies is asking, “Well, okay, here’s something that he wants. Maybe I can turn that to my immediate commercial advantage.” Given that Hutchison did pretty well with the port sale, that’s not a bad role model for other companies.

GF: You seem very optimistic overall regarding the new administration’s trajectory and its trade policy.

Ross: Well, I am, but with one big caveat: It has to be coupled with enactment of his tax and deregulation policies. Remember, if Congress doesn’t act, the tax cuts that he enacted in his first administration will automatically go away, which would amount to a tax increase on corporations. Coupled with the tariff policy, it would be a heavy burden. That’s why it’s important that this happens.

It’s also quite important to bring down the cost of government. I’m a big fan of what Elon Musk and Trump are doing, even though I’m sure they will go too far in some cases because they’ve been moving so quickly. In some cases, they’ll have to recalibrate their course, but it’s important that Trump’s overall policies are brought to bear. It would be much better for our economy if his whole package were to go through rather than just the trade package.

In the defense sector, one of his big objections to Europe, and to a degree Canada, is that they haven’t been paying their fair share of NATO. And that’s put an undue burden on the US.

That’s changing. Indeed, some Europeans are talking about going well beyond the 2% of GDP for defense that had been NATO’s target.

You have to look at the whole set of programs. Cutting down on the ability of able-bodied people to get big [government] benefits, in many cases getting more compensation than when they were working. That will go away and will be a constructive thing for our economy because we need a higher degree of workforce participation. To grow more rapidly, we need the workforce participation rate to rise above 63%.

GF: Do you have any other concerns?

Ross: Well, there’s always the danger when you’re trying to change a lot of things in a lot of geographies all at the same time. There’s always the danger of overextending and making real mistakes. He needs to move rapidly and on all fronts for a domestic political reason: Anything requiring congressional action that isn’t completed by September will be difficult to pass, because by then, everybody in Congress will be focusing on the midterms, and they’re going to be less inclined to do anything that’s controversial.

GF: Are there any issues in which you part company with the current administration?

Ross: There are areas where we do disagree. For example, as you’re probably aware, I wrote an editorial in The Wall Street Journal supporting the Nippon Steel takeover of U.S. Steel, which is directly antithetical to US government policy. So, while I’m broadly in sync with what they’re doing, there are some very specific parts where we naturally disagree—very much.