Good words are not an elite taste

Americans wake daily to the spectacle of Washington officials saying startling things. Media outlets answer, wielding fact-checkers as defensive weapons. In the process, these outlets recommit the sin for which they were slammed in the last election—condescension to Trump voters through the posture that they alone hold truth. The fact-checkers may be right, but the bigger puzzle is why they became necessary in the first place. Why does the ordinary person listen when powerful people spout lies and oddities that any ordinary person couldn’t get away with saying?

For instance: The forty-seventh president said Ukraine started the war with Russia. And the president’s First Buddy promised to put a government agency into the woodchipper.

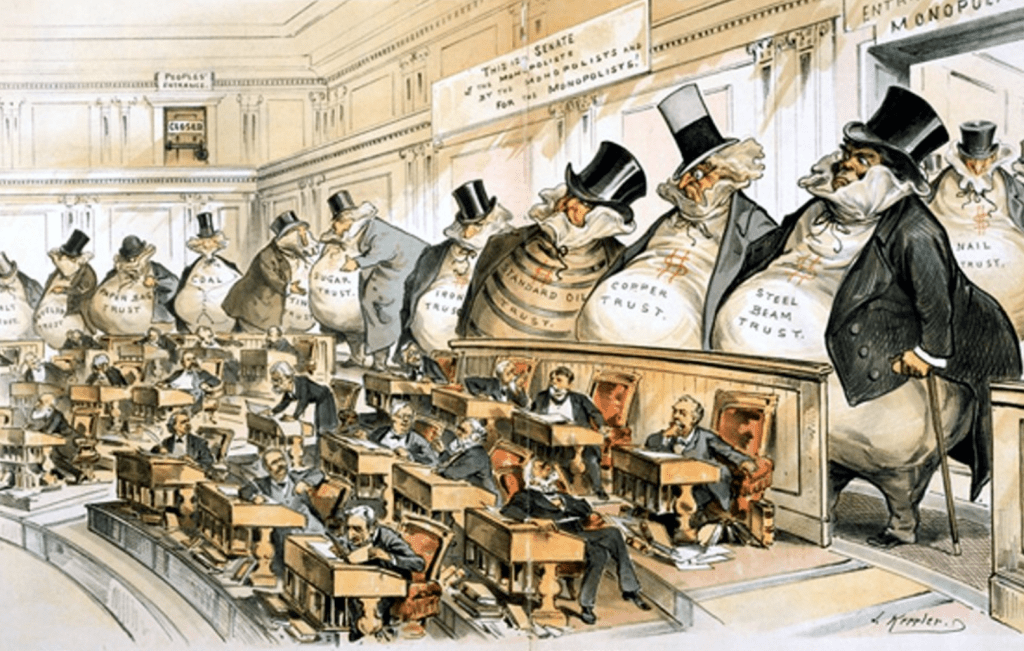

Americans might listen to the president because he is president, but the other man’s claim to our attention is shakier. Were government-waste reduction as bloodless as the bureaucracy it aims to reduce, the slashing done by Trump’s servant might make sense—even if having an unelected executive-branch functionary do it contradicts Trump’s claim to liberate the American people from unelected functionaries. Unlike cabinet secretaries of real departments, this efficient henchman was not confirmed by the people’s representatives. He is the head of a department that is not a real department, which means that he is technically the head of nothing but rather serves at the pleasure of the president, like a jester.

Funnily enough, Saturday Night Live was airing its fiftieth anniversary celebration a few days before Elon Musk was wielding a chainsaw on stage at CPAC, a gesture SNL will surely spin to gold from now on. When Musk hosted the show in 2021, he was endearing. He listed his industrial accomplishments and joked that after all those triumphs we should hardly expect him to be a regular guy. His mother, a charming silver-haired woman, appeared at the end of the monologue and gave a few scripted jokes at Elon’s expense. It was nice. He got a lot of mileage making gentle fun of himself, a nerd flaunting his awkwardness to rib New York cultural elites for the benefit of the American viewer. It’s a much better look than flaunting his wealth now to rib Washington cultural elites—the ones in the civil service—for the benefit of the American viewer. Were it imaginable that Trump, Musk, and retinue were out there fighting for the good of nice grey-haired ladies, the present weirdness might go down more smoothly.

Despite the funny hats and silly props, the man is hard to take seriously as a clown because he is the richest man on earth. This fact explains better than anything else why people listen to him, to them. When you’re rich they think you really know.

That line comes from Tevye, the poor Jewish milkman from Fiddler on the Roof, strutting and chuffing around livestock in his barn to imagine what it would be like not to work hard and not to live hand-to-mouth. Running through the material charms of money, Tevye gets to this one—that other men would ask his opinion and fawn on him. His wealth would speak for him, or at least make others behave like they should listen.

Surely we know better. The U.S. cultivates homegrown anti-intellectualism, but if our anti-elitist strain does anything for us, it should inoculate us from powerful plutocrats mooning for the camera to flatter us to submission.

The forty-seventh president can say startling words that do not ring true. Yet still we listen. Some of us nod. Some dispute. Sometimes we get no further. The tragic condition is, first, credulity accorded to powerful rich men, and second, polarized discourse that seems incapable of holding goods in tension.

Matters of state met lately with a chainsaw could be addressed with more nuance. Government can be inefficient and humans do make mistakes, and this combination yields some waste, fraud, and abuse. But still, our government accomplishes many worthwhile goods, as self-governing people have the right to expect. Downsides often are braided inextricably with upsides.

We can consider cases like USAID, which functions imperfectly to deliver food to starving people or to rescue tsunami victims or to save babies from HIV infection. Besides, those gestures extend the soft power of the US in a world where this kind of power steadies our place in the global balance and boosts our own sense of the kind of country we are. We’re the good guys, the people on the side of freedom.

Or we could consider Ukraine. It would be good for the war to end. But to end the war by giving in to the aggressor betrays our friends and our place on the side of freedom. If habit equips Americans born in the twentieth century with confidence about anything, it’s that we usually feel safer on the side opposite Russia.

And then there is the reality that countries must have borders, and newcomers’ claims on American resources affect citizens. But also, the suffering and determination that bring some migrants here should move citizens, themselves shaped by suffering and determination, to interpret charitably migrants’ desire to come. All that effort to reach the U.S. might look almost like some kind of tribute—maybe a tribute to freedom, or maybe to us, the good guys.

Digital communication was supposed to bring a new dawn, everyone everywhere having access to information. Instead it has eaten away our treasures—attention, trust, shared stories. But the potential for much better conversations still exists. One of the great joys of our time is accessible abundance of good writing, about gila monsters and truckstop chapels and bookshelves. Those are not topics of merely upper-class interest. Writers with wide-open eyes and breathtaking prose offer a kind of fellowship and instructional camaraderie that may be peculiarly, beautifully American.

In spite of our quirks and short-circuits, Americans always have grown a hungry humble curiosity—what historian Joseph F. Kett calls The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties. Citizens far from educational privilege have claimed as birthright a glad meeting of the world, working-class Shakespeare buffs, National Geographic subscribers, Great Books clubs. Those who had neither time nor money for college need not consider the world closed to them.

Rich people acting low to flatter the common man should offend democratic sensibilities. Good words are not an elite taste. We all deserve fine, true ones.

Agnes R. Howard is author of Showing: What Pregnancy Tells Us about Being Human and is grateful to have been a contributing editor for Current.

Image: Joseph Keppler, “Bosses of the Senate” (January 1889)