Get ready for a long ride into the world of competition in the AI industry!

I’ll tackle the above in this massive issue, so hang tight and follow me along.

In the meantime, if you want to grasp the whole AI ecosystem, that’s your go-to map.

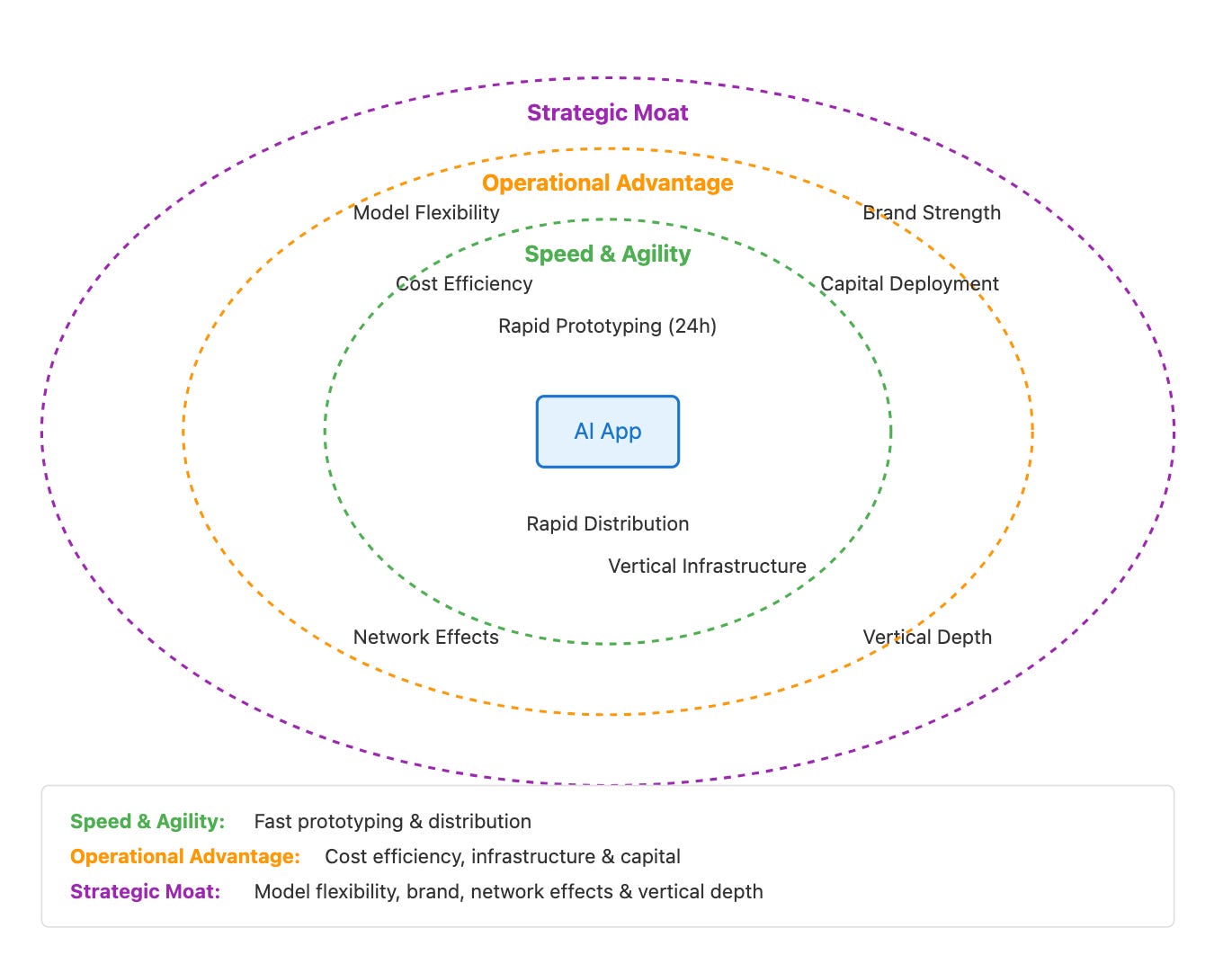

In AI Moats: Part One, I’ve tackled the build-up of moats on the application layer side.

I’ve called it “Part One” because this was dedicated to the applications side of it (the so-called “wrappers”) to highlight how not only you can, but now more than ever, it’s possible to get momentum, build something quite valuable, out of nowhere and with very low entry barriers.

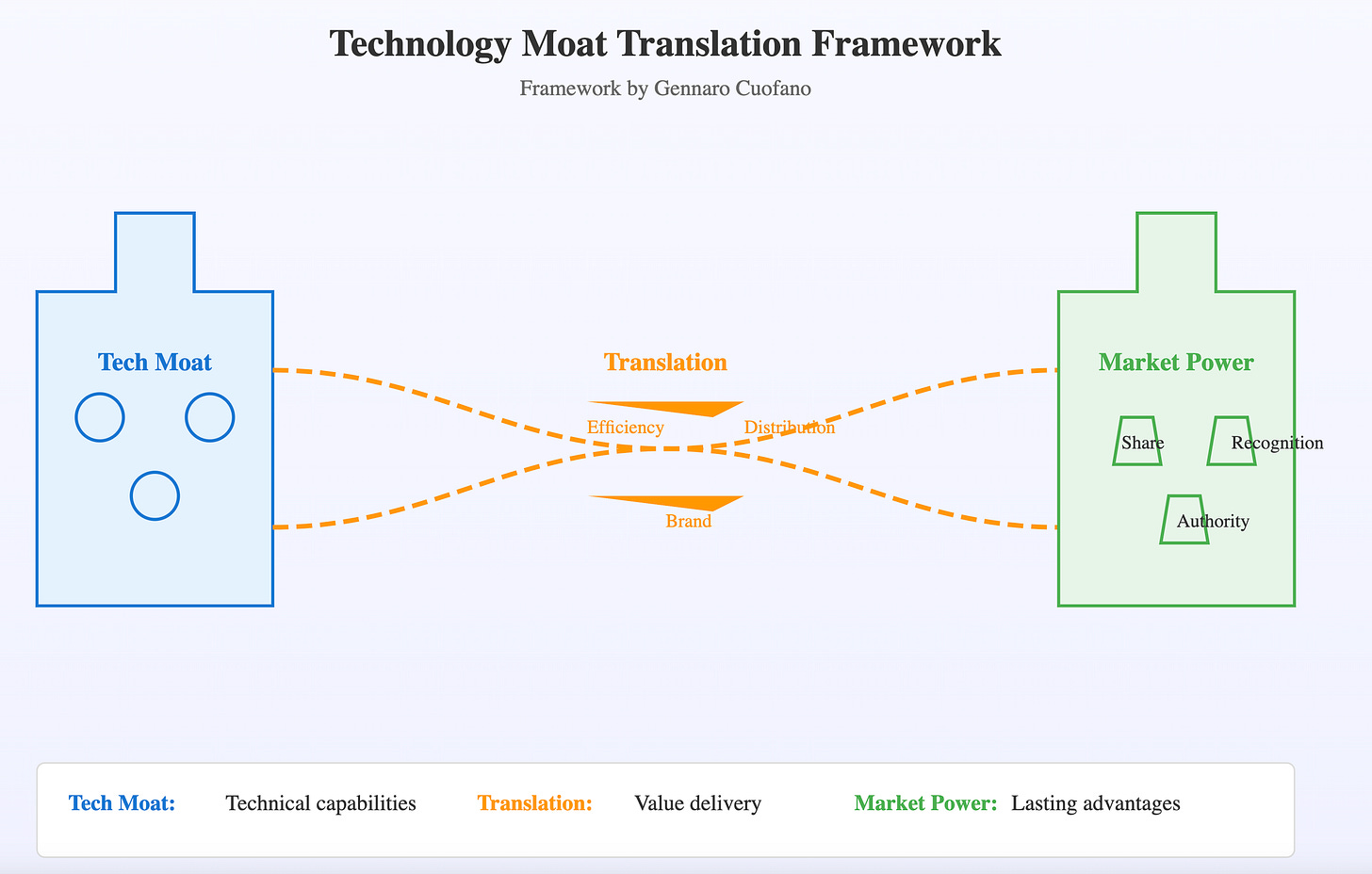

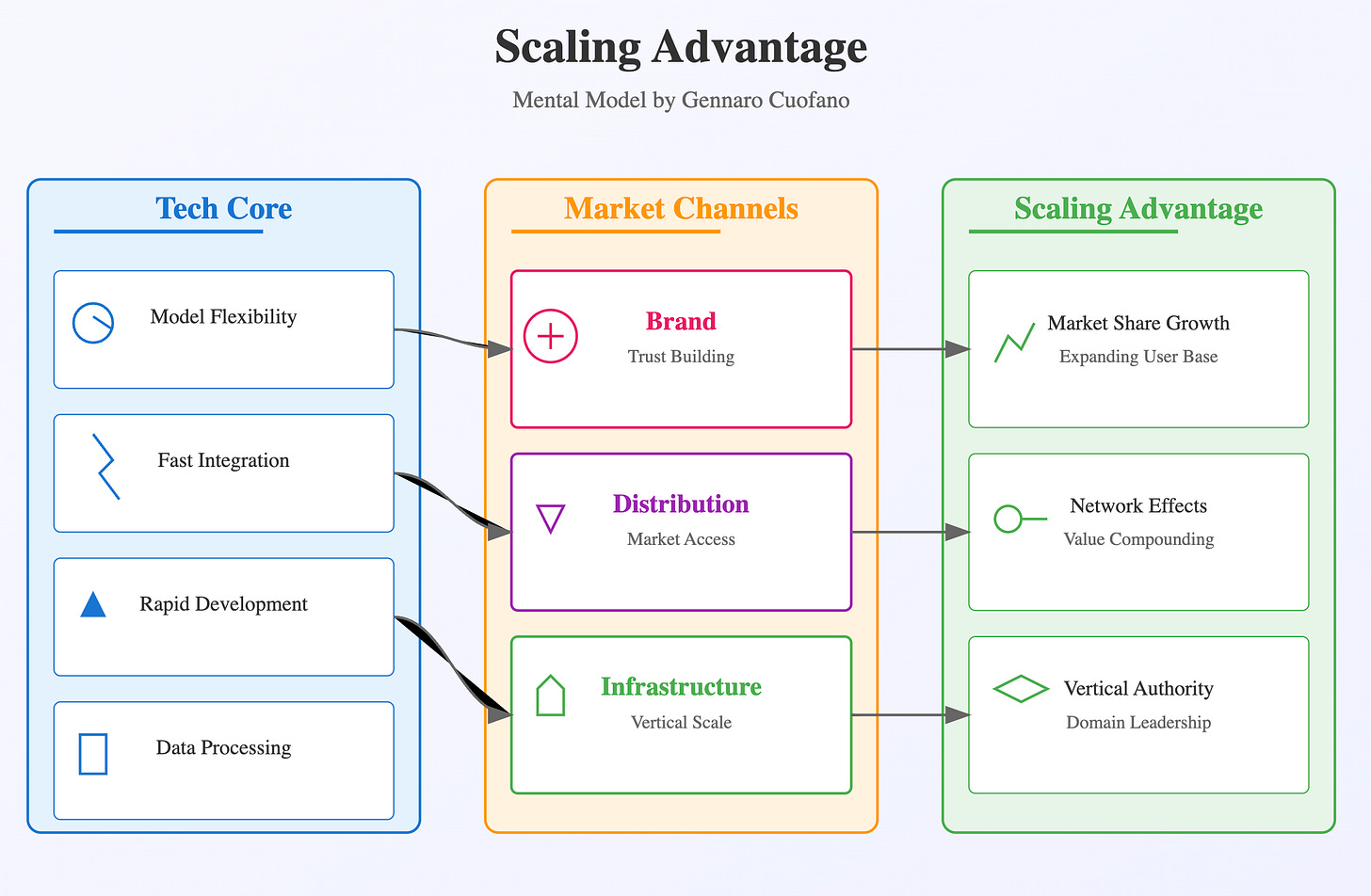

Yet, I’ve also shown how that speed and capability to tune an app and bring it to the millions fast must be translated into vertical infrastructure/architecture, branding, and distribution to become a moat.

I’ve mapped everything into the Moat’s three circles, moving from speed and agility to strategic moat.

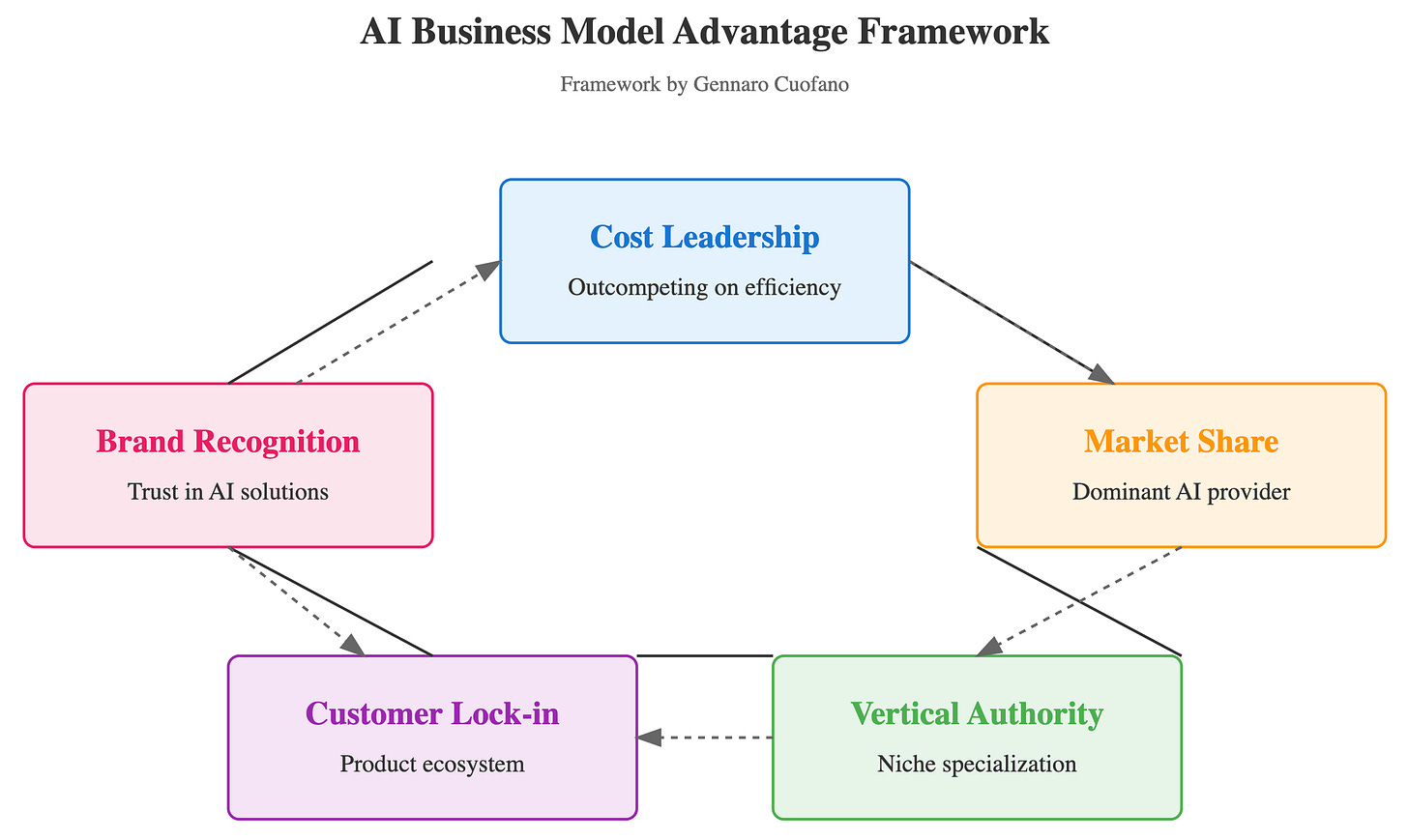

In the end, in competitive moating, I’ve explained how that tech advantage translated into a business moat.

That is what it means to build an AI-native business model.

From there, you get a scaling advantage.

That is at the core of what I’ve defined as an AI-up

Back to the foundational stack, though, things are slightly different.

This is part of an Enterprise AI series to tackle many of the day-to-day challenges you might face as a professional, executive, founder, or investor in the current AI landscape.

Or pretty much, the guys, like OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, and Google, who need to keep pushing these AI models to the next level to maintain a competitive edge, thus also wide market shares of the AI market.

Many people are surprised when tech gets commoditized quickly.

But that’s a fact.

Yet that doesn’t mean you can’t build a competitive moat out of it, but it won’t be just on the core tech; rather, it’s how that core teck will translate into accelerated growth, distribution, and branding; you get out of it to lock in a market.

However, before we get to it, there are a few concepts to master.

-

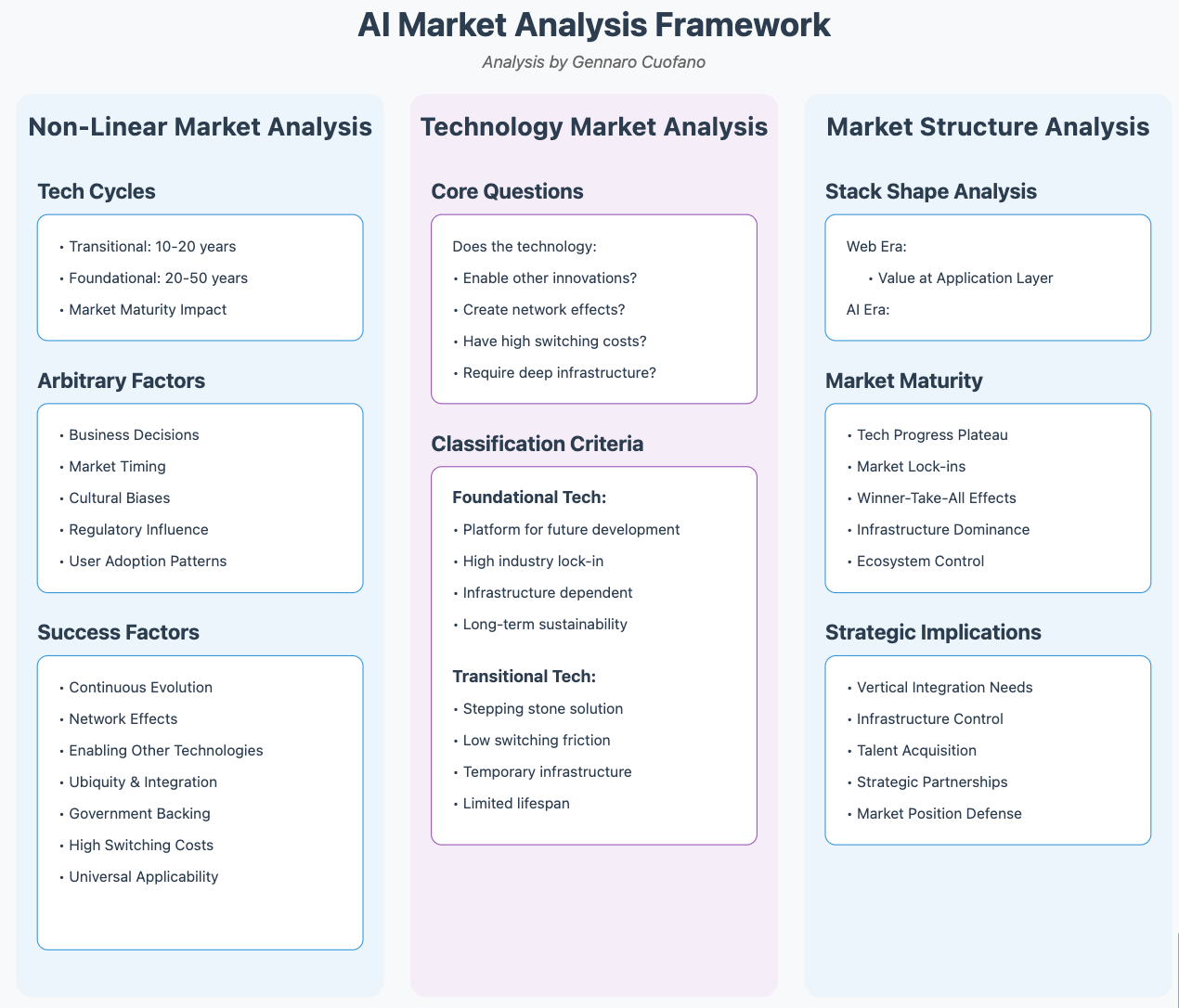

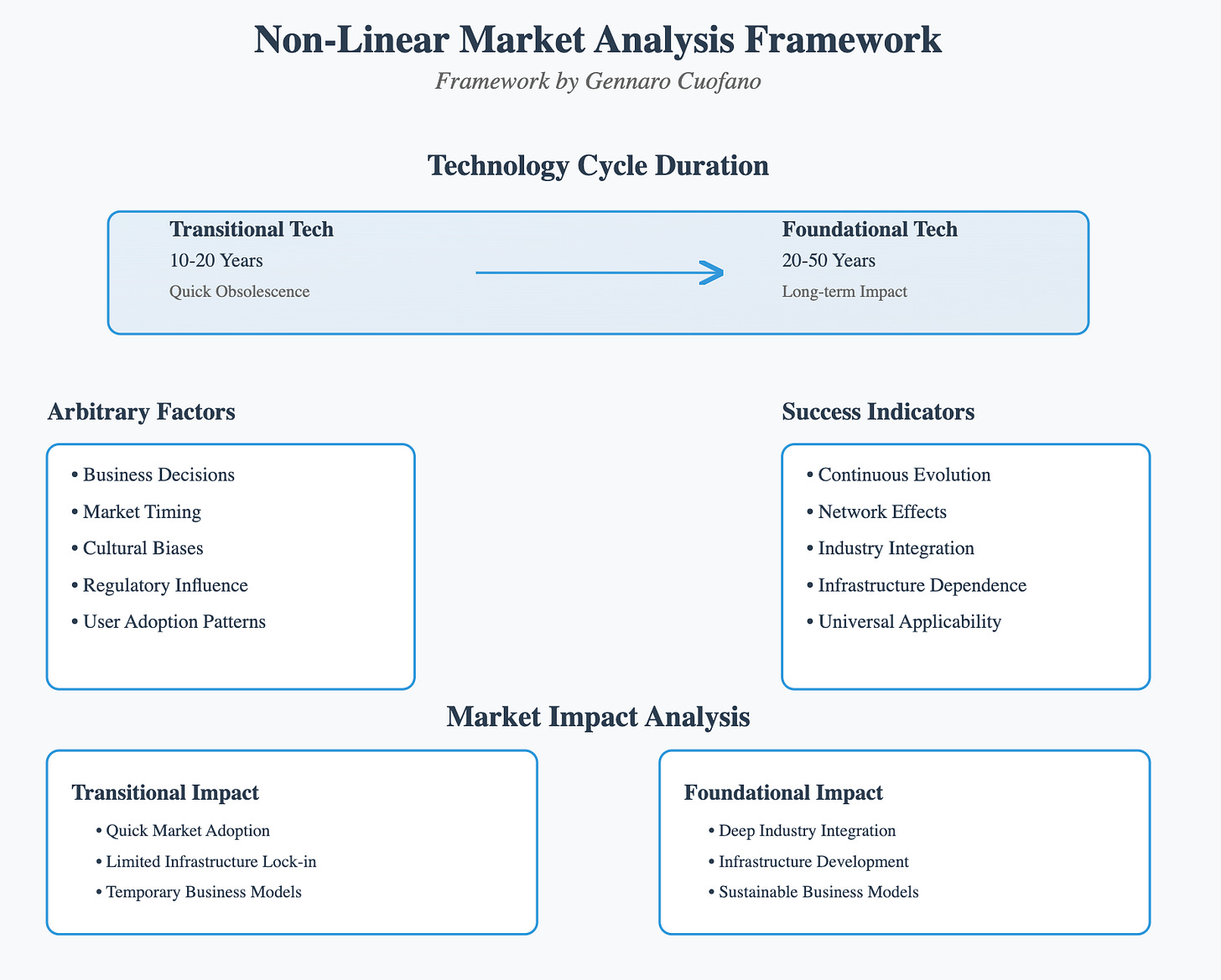

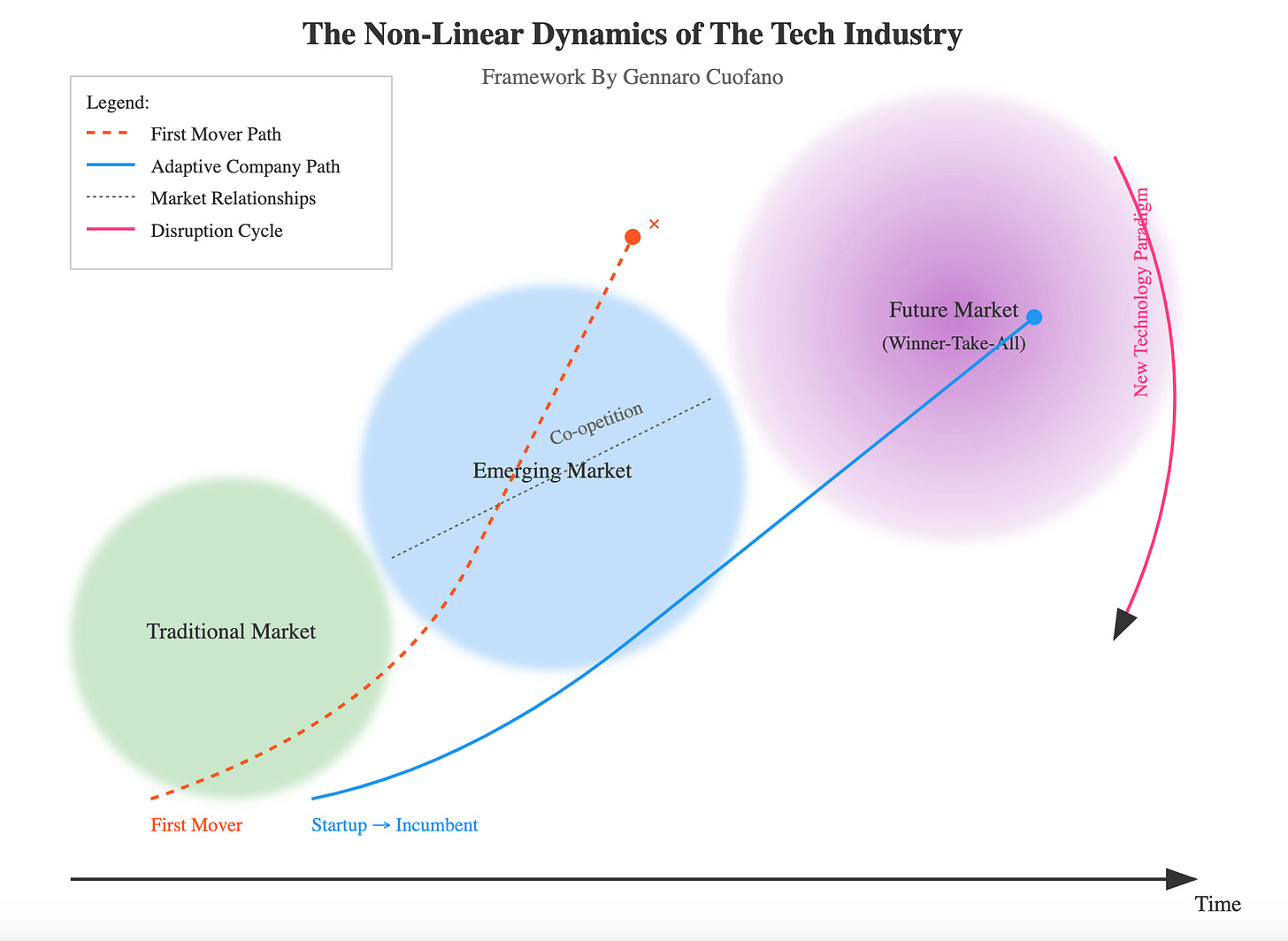

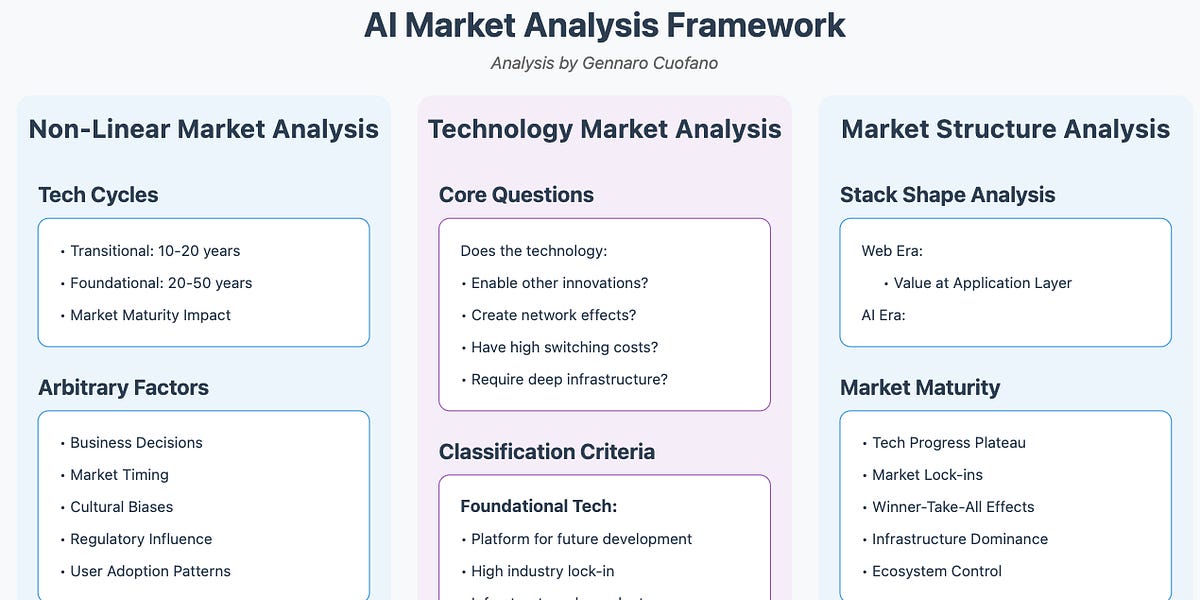

First is the non-linearity of it. That matters because we want to understand whether the underlying context is shifting quickly toward a new paradigm, whether we’ll sit on top of the current paradigm for long enough to build a solid business model, or yet even if shifting what transitional business model to use to get there (non-linear tech market analysis).

-

Second, what’s the underlying context? There, we’ll need to consider whether we are in a transitional or foundational market (contextual analysis).

-

From there, go back and look at the nature of the developing ecosystem, as each new ecosystem will have its own dynamics (market structure analysis).

In non-linear competition, I’ve explained the axioms of competition in a tech-driven world.

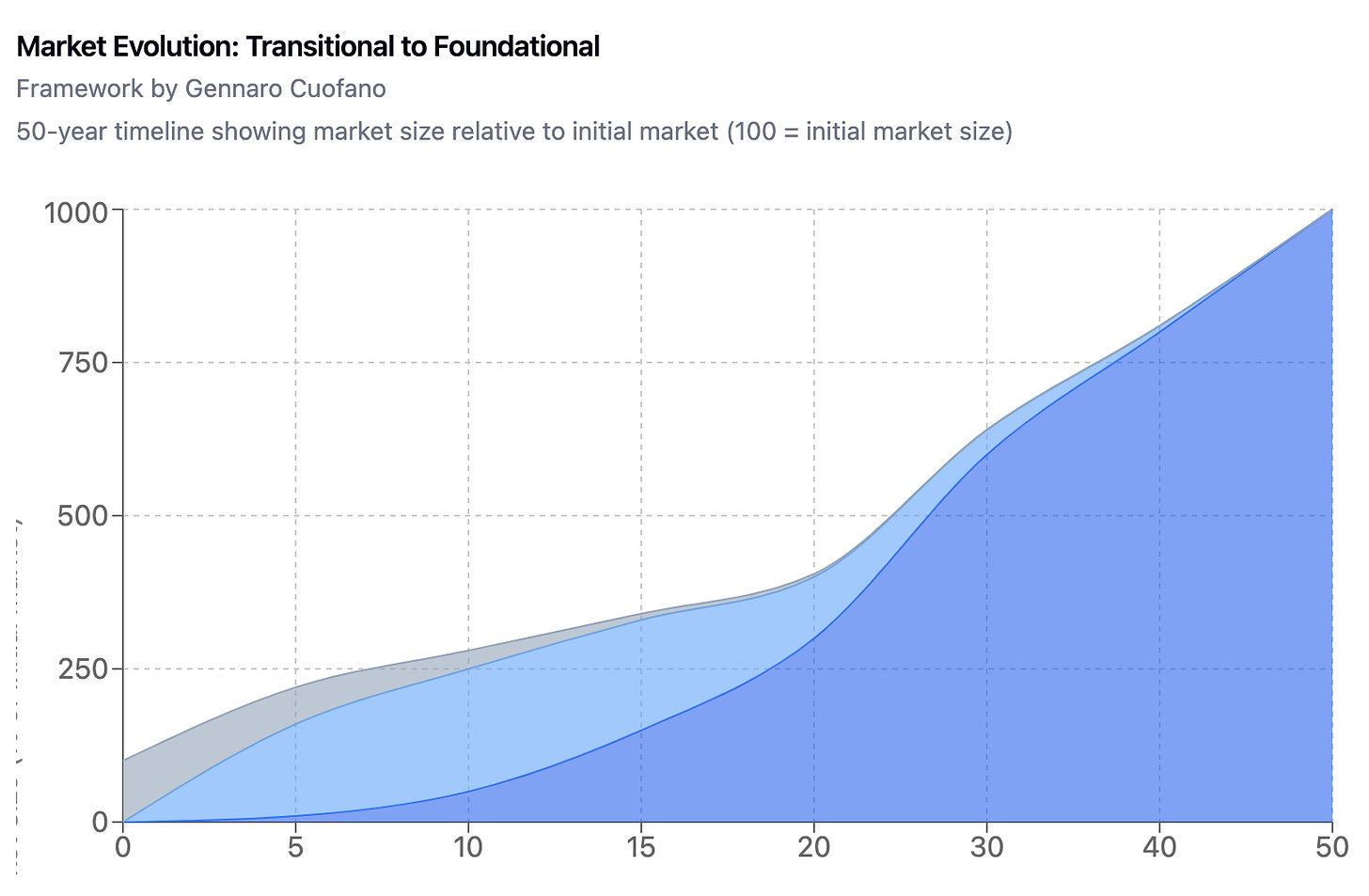

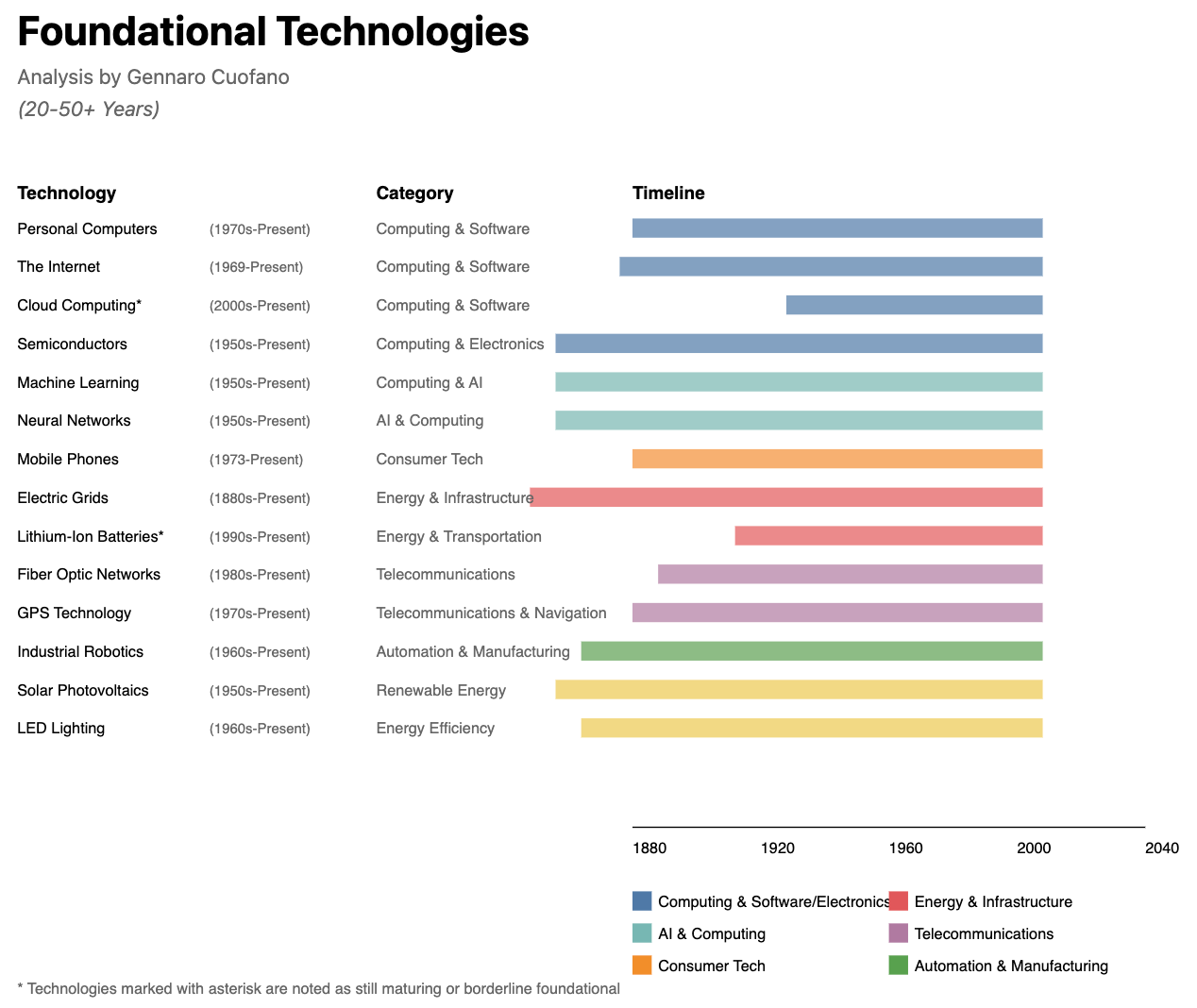

The key take from it is how a tech moat alone is hard to maintain, as the technology cycle (depending on whether it is foundational or transitional) can last anywhere between 10-50 years.

And that means if you’re operating in a fast, transitional tech cycle, you won’t be able to build a solid foundation (to last at least 20-30 years) as a set of emerging techs, which might converge into a whole that makes it hard to predict, as of now, what will be the foundation.

That will also make it quite hard to understand how to invest the growth capital available, as you’ll need to be on the lookout for the developing “foundational cycle” that will become the foothold for the business for 20-50 years.

The reason is that for a tech market to mature fully, it will need to reach the maximum level of scalability, which comes with making the tech available to the largest number of people at the cheapest.

Thus, in the process of maturing, many techs that seemed to work fine at a level of scale after a threshold dies down, giving space to other techs that, from an ecosystem perspective, might make the market scale, thus mature into a mass market.

That’s where we need to understand a bit where we are.

The tech world is tricky, as it goes through such fast cycles of innovation, where competition, at specific time windows, gets so fierce that it generates a plethora of new tech.

Yet, a lot of it won’t survive the long term.

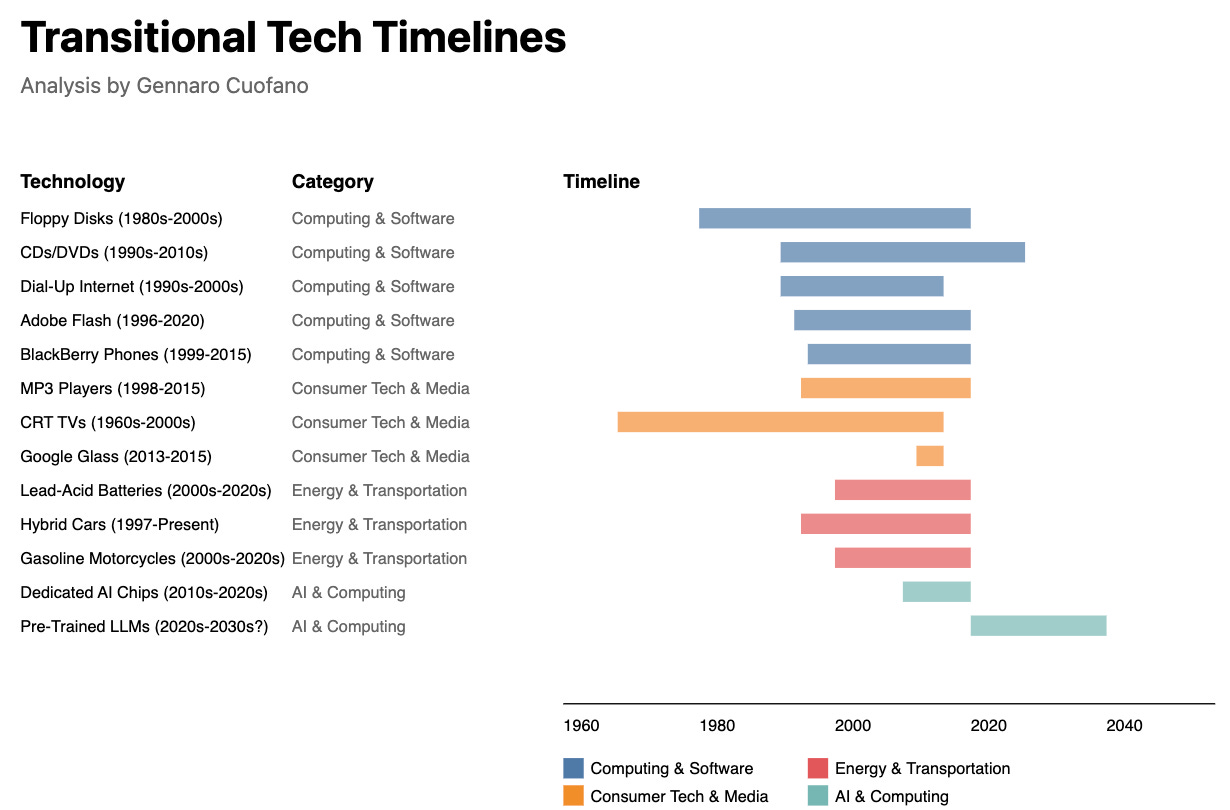

As an example, take some of the transitional tech below:

The reason for some of these “transitional tech” not to survive is tied to few factors:

-

Technological Evolution: More powerful, efficient, and scalable alternatives replace outdated tech. Take the case of floppy disks, which carry low storage capacity and slow speeds and are replaced by USB drives and cloud storage. Yet Dial-Up Internet, which experienced slow speeds and reliance on phone lines vs. broadband, has fiber-optic Internet with its own super-fast infrastructure.

-

User preferences/Features are set into broader tech: Consumers are shifting towards more convenient and integrated solutions. Take the case of MP3 players, which are now integrated into smartphones.

-

Economic Factors: Cost savings and business models make specific tech unsustainable. Take the case of CRT TVs: Expensive, bulky, power-hungry

vs. LED/OLED TVs.

-

Regulations & Security: Government policies and security risks phase out vulnerable technologies. Take the case of Adobe Flash with Frequent security vulnerabilities vs. HTML5 and WebGL.

-

Business Model Disruptions: where new business models make old technologies financially unsustainable. A classic example is DVD Rental Stores vs. the Rise of digital streaming platforms Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon Prime.

-

Infrastructure Upgrades: New networks and platforms make old solutions impractical. Take the case of gas vs. electric vehicles.

Other factors are a bit more arbitrary, so this points out how the tech sector itself isn’t prone to competition interference.

Some factors like:

-

Business & Corporate Decisions: take as an example Betamax vs. VHS (1980s). Betamax was technically superior to VHS, offering better picture quality. VHS won because Sony restricted Betamax licensing, while VHS was widely adopted. The Arbitrary Factor: Business strategy, not technology, decided the winner.

-

Market Timing & Consumer Adoption. Take Google Glass as an example. Launched in 2014, it was a very cool product, but people haven’t used it yet, and the potential of such a device is unknown. Google pulled it off instead of iterating on it.

-

Cultural & Psychological Biases. Take the case of QWERTY vs. Dvorak Keyboard. The Dvorak keyboard is more efficient than QWERTY. QWERTY remains dominant due to historical momentum and resistance to change. Here, the arbitrary factor is inertia, so people don’t like to relearn typing.

-

Government & Regulatory Influence. Take the Example of Nuclear Energy vs. Renewables. Nuclear power is efficient and clean but faces regulatory backlash after disasters. Renewables like solar and wind received more subsidies and public favor—arbitrary Factor: Political and environmental lobbying shaped policy.

Now, let’s look at the timeline for foundational tech: