This is the fourth part of our [five? -ish? I, II, III] part series on the Siege of Eregion in Amazon’s Rings of Power. Last week, we took the opportunity presented by Adar’s absurd plan to dam a river using catapults to collapse a mountain to discuss the capabilities and functioning principles of historical counterweight trebuchets, the largest and most powerful sort of catapult. While trebuchets were powerful weapons in their day, Rings of Power, like many modern films and TV shows, presents the weapons as having orders of magnitude more range and power than they did historically, showing them used to do things that the actual weapons simply couldn’t accomplish, like rapidly demolishing a city or collapsing cliff made of solid rock in moments.

This week, with the Sirannon river protecting Eregion’s capital, Ost-in-Edhil, is now drained, the orcs begin their assault, giving us an opportunity to discuss what a more competent prepared fortress assault might look like. Now I want to note this sequence gets complicated quickly due to the appearance of relief armies, but we’re going to break this up thematically, treating the attack on the city in this post and the fighting with the relief armies in the next post. Fortunately, because Rings of Power is broadly incapable of managing cause-and-effect, the fact that not one but two entire relief armies show up unexpectedly matters not at all in the battle or to any of the important characters, which makes this sort of division of topics easier (even as it makes the show worse).

Book Note: We can essentially do just one book note for this entire sequence. We are given no details in either the appendices or Unfinished Tales on how the capture of Ost-in-Edhil was accomplished, except that it clearly fell by assault (rather than surrender) and the effort took some time: the attackers break in “at last…with ruin and devastation” and Celebrimbor is taken while fighting with Sauron himself “on the steps of the great door of the Mírdain” (Tales, 228). But that skeleton of a description nevertheless leaves room – indeed, clearly seems to actively imply the kind of slow, methodical and careful assault that is more commonly successful historically. I suspect here this is in part because Tolkien is echoing the way that historical texts, both ancient and medieval, relate the outcomes of sieges when they aren’t going to give a detailed, blow-by-blow description: there’s often an indication if the siege was long or short, if it was difficult or easy (not always the same as length) and then frequently just one or two vignettes such as the last stand of a significant figure or a notable moment of treachery or so on. Here what Tolkien gives us tells us the siege was long, difficult and ruined the city and then gives us in just a few words the vignette of Celebrimbor’s final, doomed resistance protecting the thing he cared for most, the “their smithies and their treasures” (Tales, 228), rather than, you know, the people. It is telling that this is where Celebrimbor’s final defense is held, one last statement on his character, not wholly negative but also not wholly positive either – no Ecthelion of the Fountain or Glorfindel of Gondolin is Celebrimbor.

But first, as always, sieges are also expensive! If you want to help out with the logistics of this blog and my scholarship more broadly, you can support me and this project on Patreon! I promise to use your donations to carefully construct mantlets and moveable shelters to protect my soldiers as they advance, slowly and methodically towards the walls of the enemy, rather than being picked apart by arrows. If you, like Eregion, completely lack scouts or information gathering of any kind and are thus regularly surprised when posts like this appear outside of your walls, ready to sack your homes free time, you can get a bit more warning by clicking below for email updates or following me on Twitter and Bluesky and (less frequently) Mastodon (@[email protected]) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

Swarming Like Ants

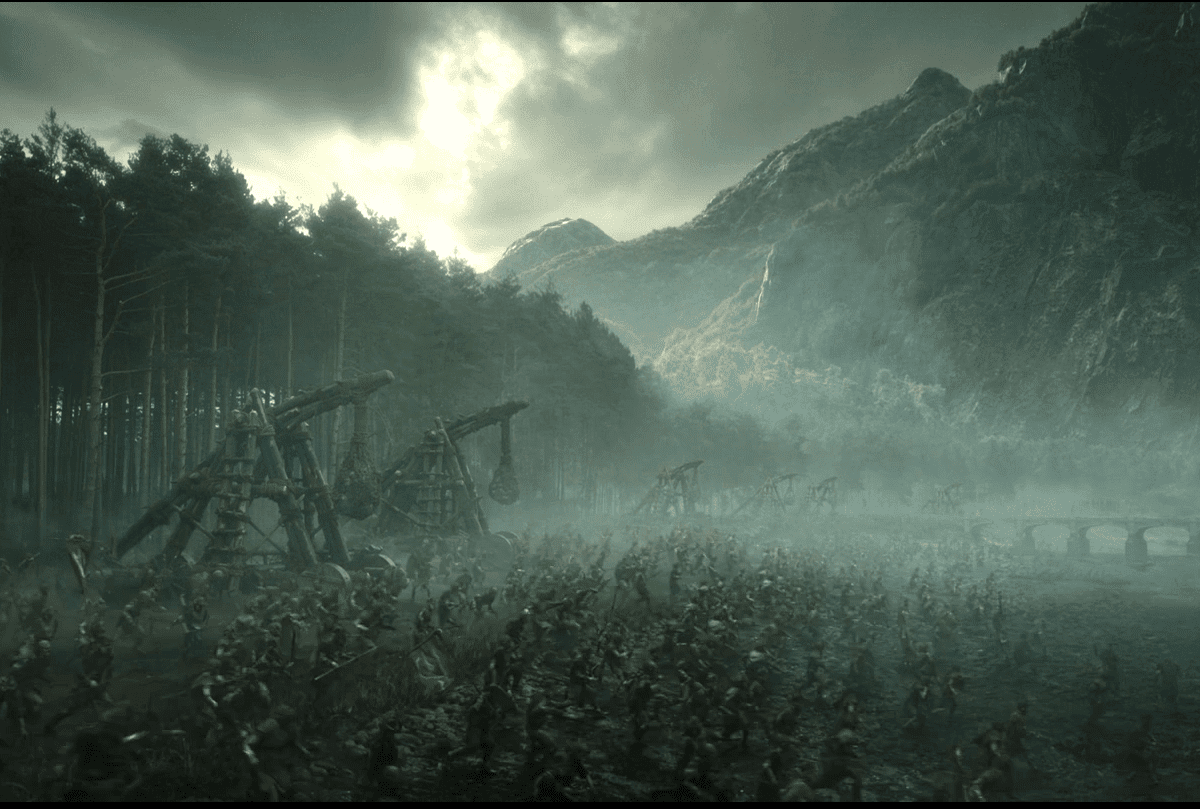

With the river now drained, Adar’s next step is to launch his orcs across the riverbed in a disorganized rush against Ost-in-Edhil’s defenses. This sort of assault is extremely foolish for a number of reasons. The immediate reason is a problem of terrain: Adar has given the river time to drain but not to dry, meaning his soldiers are likely attacking across a damp natural riverbed. When we see it, we see a bed that looks to have consisted mostly of silt and sand, which is to say, quite fine particles which are, in this case, still wet. I imagine just about anyone who has ever waded across a shallow river understands the difficulties Adar’s troops – weighed down by equipment, armored and in some cases pushing siege equipment – will almost instantly be in. This terrain is going to be difficult: wet and muddy, soldiers will sink in it, where it isn’t slick and hard to maintain balance. This is potentially the sort of muddy, viscous terrain that armies in the First World War used duckboards to cross.

Adar is attempting to charge over it.

Good Luck. With. That.

The second reason this assault is extremely foolish is actually a very old one. Adar’s draining the river hasn’t removed Eregion’s defenses, the city is still walled along the riverbed (and Adar, for whatever reason, hasn’t considered now looping around those defenses but attacks straight into them). So Adar’s implausible catapult-terraforming has merely given him the opportunity to engage in a traditional fortress assault over unusually difficult terrain – he hasn’t actually prepared at all to assault the walls themselves. His catapult barrage, as noted above, didn’t damage the defenses in any way, they were focused inside the city on fragile but militarily unimportant buildings. Adar is then hurling his army, with no real order to it, against those walls.

Indeed, this sort of attack is such a terrible idea – and such a famously terrible idea – that it is not infrequently held out as the example of a terrible idea in military treatises. Here, for instance, is a famous passage of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, describing the perils of sieges (trans. Lionel Giles):

4. The rule is, not to besiege walled cities if it can possibly be avoided. The preparation of mantlets, movable shelters, and various implements of war, will take up three whole months; and the piling up of mounds over against the walls will take three months more.

5. The general, unable to control his irritation, will launch his men to the assault like swarming ants, with the result that one-third of his men are slain, while the town still remains untaken. Such are the disastrous effects of a siege.

Adar has not even ascended to the basic level of competence of Sun Tzu’s idiot-general-making-obvious-mistakes in this passage, because he hasn’t yet spent several months building mantlets (we’ll come to these) or piling up other works and has instead after just one day launched straight to the “assault like swarming ants” part of the battle. And note the result Sun Tzu expects from this approach with better preparation than Adar‘s: “one-third of his men are slain, while the town still remains untaken.” Poorly prepared, badly thought out siege assaults generally fail; the entire reason for the complex systems of siege engineering and large, expensive siege machines was precisely that one could not simply win a fortress assault by rushing at the wall en masse.

And here we run back into the storytelling failures of this part of Rings of Power. In the Lord of the Rings, we have two sieges: a competently executed prepared assault and an incompetently executed hasty assault. Now, both end up failing because of heroic intervention (while the storywriters for Rings of Power need this assault to succeed), but what I want to draw attention to is how the way these sieges proceed illustrates character. Saruman’s attack on Helm’s Deep is, as I’ve noted, poorly managed. His army isn’t very cohesive and is unprepared for things they ought to have seen coming. Moreover they’re also unprepared to effectively assault this fortress, having banked everything on a sapping effort with blasting fire that doesn’t expose the main citadel. As a result, the effort fails due to Saruman’s bad planning: his overconfidence and lack of field-specific knowledge show up very clearly in the way his efforts fail, resulting in him being defeated by an inferior force.

The Witch King’s attack on Minas Tirith, by contrast, is very capable executed. The Witch King has prepared specific engines, like Grond, to engage specific parts of the defenses. He has left blocking forces (the Corsairs and a wing of his army in Anorien) to isolate the battle-space. He has reserves to guard against potential problems. And his assault, while necessarily swift is methodical: trenches to protect his equipment, then catapults to start fires in the lower levels to isolate the outer defenses (something Adar’s catapults do not accomplish), then towers to engage the defenders at all points, so that there is insufficient force at the decisive point (the gate) when his main effort arrives with Grond. As a result, it takes the combined efforts of several very capable commanders to stop him: Denethor, while he retains his wits, employs a masterful defense in depth, Faramir’s ability as a captain to hold his men together is remarkable, Théoden shows excellent generalship in side-stepping the blocking force to deliver his cavalry to the battle.

And yet in all of that we learn something about both the strength of the Witch King, but also his cunning and malice, because despite such capable opponents, his plan mostly grinds on as intended: the defenders are driven in, the defenses isolated, Théoden’s cavalry engaged and put into desperate straits against his reserves. We see both the Witch King’s character strengths – cunning, intelligent, methodical and deliberate – and of course his flaws as well in that it is his arrogance that leads to his death even at a moment when his plan is probably still more or less working (Aragorn not having arrived yet).

In short in both cases the way the siege proceeds is both connected logically to the material conditions of the siege – that is, it makes basic physical sense – but it also proceeds out of the character of the characters who are conducting it. The Witch King’s ruthless disregard for life is on display in his method of attack, as is his arrogance in advancing through the gate first, so confident in his victory, as is his cunning in the fact that he had a ‘Minas Tirith Main Gate Buster’ specifically prepared and ready to go for this very moment. Equally, Gandalf, Faramir, Théoden and Aragorn’s quality all emerge when pitted against such a capable foe.

The siege set piece becomes more than just a tool for special effects, it becomes a mechanism to develop characters. We learn a bit more about who these people are by the way they behave in these circumstances and then the consequences those behaviors have in terms of winning or losing the battle.

But in Rings of Power, Adar is a complete idiotic fool whose plans are terrible and go wrong repeatedly who nevertheless wins easily anyway for no clear reason. Adar has laid a siege on a city with insufficient preparation, charging his army blindly across a mud-soaked riverbed into prepared defenses without any preparation before being suddenly and unexpectedly attacked in the rear twice and wins anyway. I think we are supposed to learn from this that Adar disregards the lives of his ‘children’ in his monomaniacal pursuit of Sauron, but what we actually end up learning is that battles in Rings of Power are like rounds of Whose Line Is It Anyway: the rules are made up and the casualties don’t matter.

We don’t even learn what kind of person Adar is – beyond his willingness to spend the lives of his orcs (although we don’t see very much of this either) – in the way he attacks. Is Adar a great tinkerer and engineer, so that he would, like Saruman attack with a new technology (blasting charges)? Is he methodical and deliberate like the Witch King, dismantling one defense after another in a series of careful attacks, long in deep preparation? We get none of this. Adar doesn’t have catapults because he’s shown to have prepared them for years or really like siege engineering, he has catapults because…Hollywood sieges have catapults. His stunt to drain the river doesn’t seem to come from some established deep knowledge or interest in hydrology (though this would have been a clever thing to set up, given the equally silly role of flooding waters in Season 1 – but Adar has no hand in preparing that!) or geography.

We learn nothing about Adar, who remains a very flat character, a ‘Lord Father’ who doesn’t care much about his children and is obsessed with his war against Sauron. He doesn’t seem to believe in much, or be interested in much, or have much personality. Like Bronwyn, like Arondir, like Waldreg, like Mirdania (I had to look up some of these names) and like so many others, they kill him at some point and I felt nothing.

Making Works Work For Your Work

What ought Adar be doing? He should be doing quite a lot of work, actually – building quite a lot of works. ‘Works’ in a military context (particularly a historical one) is the word for basically any constructed element of a battlefield, particularly field fortifications. Because there’s actually quite a bit Adar can do in order to make his assault on the city more likely to succeed.

As we’ve already noted, this task would probably begin with circumvallation: building a line of defenses around the city, parallel to its walls (or around the bridges and gates, in this case) to prevent the enemy from advancing out. This matters to Adar both because it means the enemy can’t dash out and smash his catapults and other preparations, but it also means his high value target probably can’t escape.

Book Note: The Witch King does exactly this in the Siege of Gondor, using a series of trenches (filled with some sort of flaming, perhaps magical, obstruction) to circumvallate the city and prevent the defenders from easily sallying out, while protecting the catapults and other siege engines being prepared (Rotk, 105). These works are abandoned when the Rohirrim attack, enabling the men of Gondor to sally out to support the Rohirrim’s attack as it develops, but seemingly only around the gate (where presumably there were gaps in the works to allow Grond to approach the gate).

Those defenses in turn provide the foundation from which other works can be assembled. The first task, of course, would likely be assembling the catapults, which will have been transported to Eregion unassembled in carts and need to be set up on site. Now those catapults, as we noted last time, are not going to be deployed miles away, but probably fairly close to the walls – as close as they may be safely placed, since the closer they are, the harder they’ll hit. That in turn means the catapult firing positions may also require defenses beyond the initial circumvallation. You do see this sort of thing in medieval warfare, but I will note that protected artillery firing positions becomes really important in early gunpowder warfare, where siege artillery often had to be set within a few hundred yards of a wall to have the desired effect (well within musket or counter-battery artillery range). We’ll get to what those catapults should be doing in just a moment, but once set up, they’d start doing it while the other elements of the attack are prepared.

The next problem, of course, is the river. Simply damming the river – as we see in the show – is impractical…as we see in the show (and discussed last week). But armies could sometimes divert rivers and I’d expect any real siege of a place like this – given how hard approaching the city from any direction other than the river – might have to do this. Diverting the Sirannon would be a matter of digging a canal around the back of Adar’s besieging army (conveniently serving as a degree of contravallation) and his workers would be protected from the enemy by his circumvallation as they did so. Alternately, Adar might try to build new crossings over the river, depending on its depth and speed. Because the Elves lack any kind of artillery of their own, there isn’t really anything to stop Adar’s orcs from building pontoon bridges, perhaps braced with earth and rock fill, to crudely span the river at multiple points in order to enable assault (in addition to the existing primary bridge we see).

Now of course both when building any works over the river or crossing its dried river bed, orc workers and soldiers would be exquisitely vulnerable to the defender’s arrow fire. The solution to that is the venerable mantelet (sometimes spelled mantlet), relatively small portable shields or shelters that could be moved forward as necessary. In medieval sieges, its common to see networks of these wooden barriers, providing covered attack channels to approach walls and protecting stations of archers or siege workers from attack from the wall. Large siege engines – like rams – might have full, wheeled housing covering them to prevent the operators from being engaged from the walls. The advantage on a medieval battlefield that the attackers have is that the projectiles available to the defenders (arrows, slingshot, javelins, etc.) are light enough that a relatively thin wood or even wicker framework is enough to ‘catch’ them and render them harmless. In the gunpowder era, these sorts of field defenses have to get more robust and heavier – earth-filled gabions, the ancestors of today’s HESCO barriers – and thus immobile, requiring armies to effectively ‘dig forward’ to reach a wall, in a system we’ve already described elsewhere. Because mantlets are cheap, fairly quick to make and use a locally available material (wood), an attacking army can produce a lot of them and indeed, we tend to see these used in quantity.

You can see the use of mantlets to protect archers and artillery very clearly on the left.

Of course the jumbo-version of this approach is a ‘siege tower’ – generally called a ‘belfry’ by our medieval sources. These were large wooden towers – sometimes, but not always wheeled or otherwise moveable – constructed by an attacker. In film and fiction, these invariably have boarding bridges on the top and are used to assault walls, but that was actually a far less frequent way to use them. Instead, the normal use of siege towers was to create elevated, protected firing positions and to thus screen the advance of soldiers on the ground. Archers (or small catapults) elevated on the tops of these towers could sweep the fighting positions of the defender’s walls and towers from above, clearing defenders from the wall and thus neutralizing enemy ranged fire, allowing for a safe approach to the wall. In the case of Ost-in-Edhil, the presence of the river is going to mean that – either crossing bridges or crossing the riverbed – these towers are going to require some extra engineering, using wood boards and other constructions to create a flat, stable surface for them to move over. But that’s not a wild thing to do: we see Neo-Assyrian artwork from the early iron age already showing ramps and other constructions used to provide towers with easier routes to overawe enemy defenses.

In any case, Adar does exactly none of this. Not only do his orcs not have any siege towers to try to suppress the defenders or mantlets to protect their advance, they don’t even carry shields, meaning that every single orc is presenting a full body target to a city full of Elven archers. At least the Uruk-Hai at Helm’s Deep brought shields (in both film and book, TT 162-3)! We need, at some point, to return to the question of the lethality of arrow volleys against armored foes (particularly the Hollywood trope of huge casualties from mass volleys of arrows) but this is actually a force of unshielded, unprotected and relatively light infantry (we see bits of fur, a lot of leather, some scattered mail in their armor, but nothing uniformly heavy enough to resist war bow shot at medium or close range) attempting to cross rough terrain into archers who are on fortifications.

In short, this is an assault that would fail. Absent any kind of protection, these guys would begin taking losses quite quickly while – for reasons we’ll get to in a moment – the work of actually attacking is going to require them being within bowshot for quite a while as they work on overcoming the city walls. And while in real battlefields there is a lot that is greatly reducing the lethality of arrows – accuracy, shields, armor, distance and so on – such that only a small percentage of arrows are lethal, these orcs are charging Elven archers in the open, being hit by direct (rather than high arcing) fire, while unarmored, unshielded and unprotected, so we might expect most arrows to find a mark. And a good archer can put an arrow in the air around once every six seconds or so, so those casualties would accumulate very quickly. There is a reason no one attacks like this.

As we’ve seen in the book trilogy, orcs are not possessed of superhuman morale or cohesion – indeed, sometimes rather the opposite – and it would be extremely hard to get human infantry to maintain contact under these circumstances. Raw numbers here may not help the orcs much: it doesn’t actually take very high casualties to break the cohesion of most units; note about Sun Tzu describing an assault ‘like swarming ants’ which nevertheless fails, accomplishing nothing, despite its presumably tremendous numbers (in practice, such careless assaults are rare in warfare because they’re so obviously foolish to anyone not making a prestige TV show). And with no fortified, protected intermediate positions – because, again, no circumvallation or mantlets – once they started falling back, they’d fall pretty far back, at least all of the way out of bowshot.

Of course, this is Rings of Power, so Adar’s lack of preparation or planning doesn’t matter and instead his orcs simply push through by dint of numbers, which now brings us back to the orcs, their archers and catapults and the strange sort of ram they bring.

Orcish Machines

Nevertheless, Adar’s orcs now approach the wall, moving across a silty, muddy riverbed that still has pockets of standing water in it – I cannot stress how terrible a sort of terrain this would be to try to move an army over – and begins attacking the walls. To overcome the walls, the orcs have a small number of their own archers, catapults (that they don’t use), some ladders, and a machine that gets called a ‘ravager’ (as if that is a standard kind of siege engine) which makes no sense.

No part of this assault package is deployed effectively or makes sense.

We can begin with the archers. Now, employing your own archers (or slingers or other missile troops or even small bolt-throwing torsion catapults) to try to fire back at defenders on a wall was a standard sort of thing one did in sieges, in an effort to suppress the defenders and thus enable the rest of the army to accomplish whatever it was trying to do within bowshot. But absent any protection, archers on the ground were at a huge disadvantage to archers on the walls.

Now, the orcs here have one advantage which is that – as is common in fantasy film – the Elves have designed their wall badly. It protects the archers really only up to the waist. Instead, in practice walls were – from quite deep in antiquity – built with crenelation: alternating merlons, the raised part, with crenels (the space between the merlons) to create that classic tooth-like or zig-zag pattern you see on castle walls. In film, these merlons are often quite low, but actual merlons are generally quite high, significantly taller than a man and often feature firing slits carved in them. An archer behind a merlon is thus quite fully protected. Even when standing in front of the crenel, the archer provides a really hard target, because the parapet of the wall protects him up to the waist and the effect of the height of his position makes it quite difficult for an archer on the ground to actually hit the exposed upper-part of a man on the walls.

Meanwhile the archer on the ground is really vulnerable: the height of the walls means that the defenders are firing down, which is both going to modestly increase the lethality of their shots as their arrows accelerate downward, but also enable them to fire over shields and other protections. Of course the famous Roman solution to this was the testudo, the moving box of shields, held overhead as well as in front, but our orcs here have no shields so that option is unavailable to them. Attackers might try to even these fearsome odds through the use of mantlets to create protected firing positions of their own or siege towers to create elevated and protected firing positions, but our orcs have brought neither, so their archers are sitting ducks out in the open firing back at Elves they can barely see, much less hit.

One solution to this for the attacker is to remove the crenelation and this was actually one of the quite valuable tasks to which catapults could be put. Even if the main body of the wall was too thick and strong to be breached by catapult, the parapet (the entire raised structure above the wall) and its merlons have to be much thinner and more fragile, relatively easily smashed apart by catapult rounds impacting. That might kill defenders, but more importantly it removes the cover they would use, allowing the attacker’s archers – again, all the better if operating from a siege tower – to sweep the walls. Even if they cannot breach the walls, this is what Adar’s catapults should be doing. Rather than lighting some apparently purely cosmetic fires in the city or landscaping a local mountain, he ought to be aiming to strip away the towers and crenelation of a key section of the wall so that when he attacks, it will be much harder to defend.

Of course, he doesn’t do this and so his orcs are attacking against large numbers of Elven expert archers who are basically untouchable behind a protected parapet (however badly designed) while advancing unprotected and almost unarmored in the open without shields over bad terrain, but because this is Rings of Power, nothing matters and his forces succeed anyway.

If you look closely, you can see the attack involves moving siege towers up earthwork ramps topped with smooth wooden pathways, while supported by archers on the ground who are protected by larger wickerwork shields or mantlets or deployed in supporting towers.

The (Neo-)Assyrians were really good at siege warfare and this relief was about communicating that fact to the viewer.

All of which doesn’t matter unless he can either get over top of the walls (escalade) or through them (breach). Catapults might accomplish a breach, given enough time, but it was also absolutely possible to build walls thick and stout enough that almost no amount of catapult bombardment, even from large trebuchets, was going to produce a breach. It’s hard for me to get a good sense of if the walls of Ost-in-Edhil are this thick above the waterline, but given that Adar doesn’t even try, I am going to assume they are. They would certainly be stout enough below the waterline, since the walls would have to be quite well countersunk (that is, the wall structure continues below the surface of the ground) well below the riverbed (or they’d fall over) and either able to resist the pressure of the water (if the ground-level of the city was lower than the top of the water) or be backed by earth-fill (if the ground-level of the city was higher than the riverbed).

Adar does bring ladders to try to scale the walls. This would actually be quite tricky in practice: scaling ladders need to be the correct height. Too low and the soldiers climbing them can’t reach the battlements; too high and the ladder is in the way, making it difficult to climb off and over the parapet. That would be a particular challenge here because of the river: before the river is drained, Adar has basically no way to really know how much length to add to the ladders to account for the depth of the riverbed. But even if the ladders are correct in height, as we’ve noted before, ladders are a pretty poor way to attack a well-defended wall and pure ladder-escalade is basically always going to fail if there are significant numbers of defenders at the point of contact (as here). I assume the idea here is that the ladders occupy the defenders, but it takes a truly trivial number of defenders to defeat ladder escalade, since one man with a spear standing at the top of the ladder can defeat a functionally infinite number of men trying to climb the ladder (especially given that they lack shields or a way to damage the crenelation and thus drive the defenders away from the point of contact).

That leaves the entire attack hinging on Adar’s ‘ravager,’ which joins the Númenórean Cavalry Chain in the Roll of Infamy for bad attempts at being ‘clever’ and inventing new weapons.

Note that the machine is entirely unprotected, so any archer on the wall (for instance, one standing where the camera was) could in moments pick off basically every member of the crew – most importantly the two guys cranking the machine, without whom it cannot function at all.

Battering rams were generally covered for this very obvious reason.

The idea here seems to be some sort of reverse battering ram. The machine is brought up to the wall and big metal spikes attached to chains are hammered into the wall by orcs with large sledge-hammers (standing unproducted, in the open, while they do this, so a single archer could also easily stop the operation of the machine on his own). Then an orc (just two that we see!) manually cranks the machine, which looks to be a torsion system (energy stored in a twisted spring or rope) which when released hurls back a large wooden weight which violently pulls the metal spikes out of the wall, bringing some amount of masonry with them.

This is not a device that existed and I am honestly flummoxed as to why, if you had a device of this sort, you would use it this way. After all, if you have a torsion mechanism like this, instead of using it to pull chains there’s no reason you couldn’t instead use it to throw rocks (or swing a battering ram, but that you can do by hand), which would still work to shatter the masonry and do it quite a bit quicker. We do sometimes hear about siege grapples or hooks – the Roman falx muralis (‘wall hook’) used to pull down fortifications (Polyb. 21.27.3; Livy 38.5; Caes. BG 3.14.5) though it hardly seems to have been common and these tools – hooks on the end of poles – were worked by hand. I have to imagine they were probably used primarily against lighter elements of fortifications, like wooden fighting positions atop stone foundations (a common enough thing to do: it’s part of normal form of the Gallic fortification style the murum Gallicus (‘Gallic wall’) in antiquity and in the Middle Ages was a standard component of castle design, called a ‘hoarding.’). But the whole reason these things are on long poles is that they’re reaching at the lighter, upper parts of the defensive works, not the heavy, fixed foundation.

Instead, just like the better solution to the ‘collapse the mountain with catapults’ tactic – which some commenters have noted, in suggesting they might do it with late 19th century naval artillery, I was apparently still something like an order of magnitude or two off in terms of how much explosives they’d need – the solution here is very simple: orcs with pickaxes. If you have unfettered access to the base of the wall, no fancy torsion machine is necessary and indeed the machine does you no favors. After all, you go through all of the effort to drive a metal spike into the wall, there’s a good chance when you pull on it, it is going to tear out and bring very little of the wall with it, for the same reason that pulling a nail out of your wall does not collapse your house. But if you are just using pickaxes to chip and smash the stones until they crumble…well, that is how mining rock is done and for a reason.

So the way you would actually do this would be that once the river was drained, orcs would go forward and – probably using portable mantlet barriers with roofs on them to approach safely – assemble a fortified wooden shelter at the wall’s base. Then orcs with pickaxes and hammers could shatter and split the stones to undermine the wall. This sort of much simpler and more effective way of defeating a wall was frequently practiced, although operating on the surface near the enemy walls was an obvious liability, since defenders might sally out and contest the work site. As a result, even more common than surface undermining – at least as far as I can tell, it appears more commonly in siege accounts – was starting a tunnel some distance from the wall and advance it underground to the wall and then collapse it (bringing the wall down in the process). Such mining warfare was an extremely common part of siege warfare from antiquity onward, leading defenders to devise means of trying to detect undermining efforts, like a thin bowl filled with water, where the vibrations of the mining effort will cause ripples in the water, alerting the defenders.

One thing I hope comes out clearly here is how complex siege warfare could be. Systems of field fortifications, moveable shelters, siege engines, earthworks, mining and so on all brought to bear against a defender in order to degrade and eventually breach defenses that would have easily resisted a simple sudden assault ‘like swarming ants.’ Taking a walled city with nothing but muscle power was an extensively theorized problem in the pre-modern world. It is always perilous to say of any activity that every angle was considered, but surely most of them were. Sieges were rarely won by the clever application of a never-before-seen technology and far more frequently won by the methodical, careful application of very well known, frequently ancient, techniques.

Conclusions

From a historical perspective, Adar’s assault on Ost-in-Edhil is basically nonsense. He does almost everything that ought to cause such an assault to fail badly but succeeds easily because the plot requires it and this is Rings of Power, where nothing matters. Adar launches an unprotected assault with largely unarmored infantry over difficult terrain into archers positioned atop a stone wall, supported only by ladders (delivering his relatively light infantry into contact with plate-armored defenders) and a nonsense breaching machine, while his catapults do nothing to support the attack and instead sit idle. His men attack “like swarming ants,” but win anyway, because in this show, nothing matters.

From a storytelling perspective, I think the assault is also a failure. It doesn’t serve to really illuminate Adar’s character or Celebrimbor’s. We’re supposed to understand that Adar is being wasteful with the lives of his orcish ‘children,’ but in a battle where the casualties don’t matter and Adar has infinite respawning orc armies, this doesn’t matter. We’re never really confronted with Adar’s decision to sacrifice his troops except in seeing unnamed mooks mowed down in the background in a language film has used to just say “this is a battle” for ages. Adar’s orcs take basically the same losses to arrows as Théoden’s riders or Alexander’s phalanx in Alexander (2004) and those are commanders we understand (in the story, if not in reality) care quite a lot about their men. Whereas Peter Jackson’s films largely succeed in communicating character in these battles (even if they miss some of Tolkien’s details), Rings of Power largely fails.

But even beyond this, the decision to go with ‘Hollywood tactics’ misses an opportunity to do something new and fresh by drawing on the historical material more closely. As an aside, I think this is true of quite a few aspects of how pre-modern societies are portrayed: dispensing the tired Hollywood tropes of ‘Flynning‘ sword-fights and mud-brown hovels for historical fencing and appropriately brightly painted sets would do a lot to make a given project feel new and different.

In the case of a siege, utilizing actual siege tactics offers quite a lot of narrative potential, particularly in the form of the slower-burning prestige streaming TV format, where the time pressures of film are quite a bit less and it is much easier to utilize montage and cuts to imply the passage of time. The emotional strain of a siege on the defenders was considerable: they had to watch, largely unable to interfere, while the attackers methodically prepared on stage of the attack after another. In a show built around parallel storylines, such a siege could easily run several episodes in parallel with other stories, giving us a sense of how hopeless the defense is as the attackers surround the city, fortify their positions, begin a slow, steady bombardment of the defenses, build moles and bridges over the river, set siege towers to overawe the walls, and then begin slowly crumbling their foundations with pickaxes from defended, covered shelters, all while the defenders struggle to do anything to even really slow this effort down. If you still need the sense of Adar’s callousness to his orcs, a long siege gives you an opportunity to tell this story logistically, as his orcs steadily run short on supplies and he remains brutally committed to the effort.

Instead we get a sequence that repeatedly struggles to believably connect action with consequence. Adar aims his catapults at a solid rock face ten miles away and this somehow produces exactly the dam he needs to enable this assault. He then runs his orcs pell-mell over a muddy basin still filled with pockets of standing water, pushing a gigantic, heavy machine whose workings make no sense, and this results in such a successful siege assault that being unexpected attacked in the rear twice will do nothing to slow it down.

And that’s where we’ll turn next week: the cavalry arrives but – because this is Rings of Power – it doesn’t matter either.