Timed for the 250th anniversary of one of America’s most famous founding events, New York Times bestselling author Kostya Kennedy’s new book, The Ride, reveals fresh research into Paul Revere’s legendary ride. Read on for a featured excerpt.

I

ECHOES

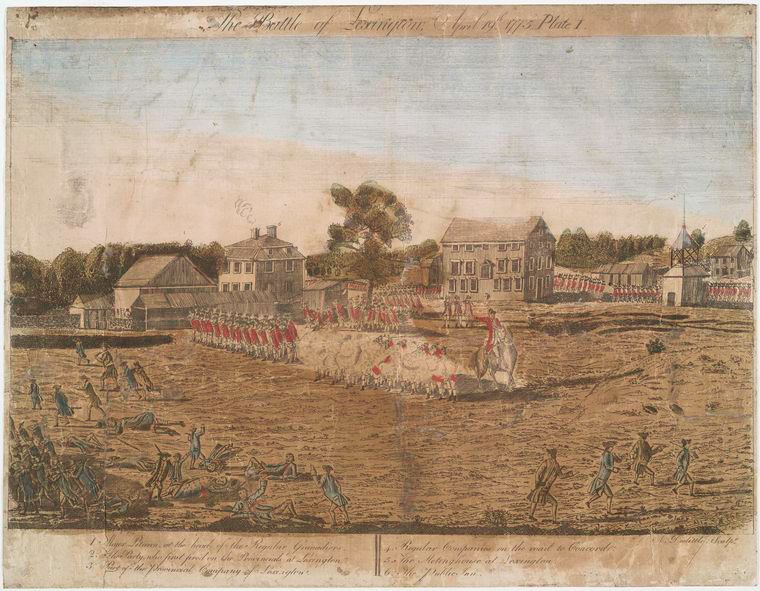

What if the militiamen had not been waiting at the Lexington Green at dawn on that April day in 1775, to test and slow the British? What if they had not then been at Concord a few hours later, 220 strong, ready and resolute on the high ground?

Those Patriot soldiers arrived by the hundreds that morning, then by the thousands, armed and keen and strengthened in their numbers. They mustered on the damp, open fields and on the forest edges along the Old Concord Road. Farmers and tradesmen, with their muskets and fowling pieces in hand. They turned back the redcoats and then fired on them in their retreat, routing them out of town and back off the land that the Patriots knew now as their own. Villagers from the highlands and the low, ministers and deists and nonbelievers, men dressed in whatever clothes they had—their patched and varied breeches, their worn straight-last boots—a hodgepodge of an earnest crew transformed by necessity and determination into American soldiers who that morning showed the will that would drive them in the weeks and months ahead, the will that would win the Revolutionary War.

Suppose they had not come that morning after all, suppose they had not been so timely in their arrival, not been so committed to their call?

Suppose instead the seasoned British soldiers, in their fine cocked hats and under their generals’ command, had in their ransacking of Concord’s Barrett Farm found and taken the stores of gunpowder and ammunition they had come to seize. Imagine if the British had caught the Americans by surprise, as they’d intended. Imagine if, in Lexington, they had killed or captured Samuel Adams or John Hancock, delivering on the bounty that had been put on those men by the king. What would have happened to the path of the American Revolution then?

If not for that first morning of battle—of impudent, plucky, stunning, and world-shifting Patriot success—would the rebelling American army have continued to mobilize so confidently? Would it have stayed so unified in the face of defeat and death, have remained so emboldened to succeed? Would the army have fared so well (even in defeat) in the Battle of Bunker Hill, eight weeks later? Would the Revolution have unfolded so quickly as it did? Would we have July 4, 1776, as our Day of Independence? Or how much longer might the British have held their grip? Into the 1780s, the 1790s, the 1800s, and beyond? And if they had held that longer grip, what might then have been the implications for the establishment and growth of the American democracy in the years and decades that followed? What would be the implications today?

When we ask these things, when we consider the plausible alternatives to the chain of events that occurred on April 18 and April 19, 1775, we are asking this: What might have happened, how might the much-documented and much-deconstructed birth of our nation have unfolded, and with what repercussions, had not Paul Revere mounted his borrowed horse and set out to ride those critical miles in those critical hours across the simmering moonlit land, to rouse the countryside and deliver the news? What would have become of the Revolution, of its crucial early days? What would have become of the whole hard, taxing, extraordinary journey to independence, if not for Paul Revere and his midnight ride?

***

Of all the Revolutionary War events that live on in collective memory—immortalized in art and prose—perhaps none conjures such a succinct image as Paul Revere galloping on his horse under cover of darkness, warning of the British threat. Perhaps no night was more critical to our fate.

If the Ride echoes in romance through the imperishable Henry Wadsworth Longfellow verse that for generations of Americans served as history, it remains resonant for its immediacy, its example of courage and enterprise and urgency. The story endures because of what it represents and what it was. Ordinary men meeting the moment of their lives. An engraver in Paul Revere, a tanner in William Dawes, a doctor in Samuel Prescott, and a network of some forty riders then coursing through the countryside, spreading word of what was at hand. Longfellow’s poem, written eighty-five years after the fact, is not bound by strict accuracy or obligation to detail— significantly, there were the other riders, too—yet the poem remains steeped in truth: a man riding horseback through the late-night hours on a fervent mission to save a nation in its embryonic, even pre-embryonic, state. It was Revere at the start and center of it all. It was Revere, booted and spurred, who raised the resistance, who helped to deliver the first, fateful stand.

He was forty years old and stood better than five feet, ten inches tall in his riding boots, taller, if only slightly, than most of the men around him. Broad across the chest and shoulders, burly. His hands were roughened from the work he did and roughened, too, from so often clutching the reins. Standing now on the far bank of the Charles, Revere could see the shape of the Somerset, the great British warship docked in the river—her masts rising in silhouette, her bobbing hull and readied gun decks a massive chiaroscuro under the night sky. Revere could feel the wet earth beneath his feet and the warmth off the mare’s body as he put a hand against her side. The deacon’s mare. “A very good horse,” Revere would say. The hint of bowleggedness that may have attended Revere’s gait in his daily life, the hitch and hint of a limp, all of that disappeared when he climbed onto the back of a horse. No one among the Sons of Liberty was a better, or more reliable, rider than Paul Revere.

He had, in the last days of 1773, ridden swiftly along the wintry Post Road the twelve score miles from Boston to New York City to deliver, as he called it, an “account of the destruction of the tea”—the seminal event that had so powerfully churned the spirit of rebellion along the docks and waters of Boston Harbor. Revere had ridden that Post Road route again in the late summer and early fall of 1774, following the stone mile markers to New York and then continuing, still farther south, to Philadelphia, a 350-mile journey in all, to arrive at the First Continental Congress carrying dispatches from the selectmen of Boston. He had made a northward ride as well that year, more than sixty miles through a hard December wind on a failing horse, to arrive at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and there pass along intelligence that led the Patriots to ambush the Royal watchmen and seize the powder at Fort William and Mary, fortifying themselves for the battles ahead. Revere rode missions at other times and to other places as well. When the movement needed a message delivered faithfully and without delay, Revere was the man to deliver it.

Now, it was the spring of 1775, warm for mid-April, and the white moon was already up in the clear, star-strewn sky, and the village roads and the country roads were quiet. At least seemingly so, for the moment. Rain had fallen that afternoon, big drops and then a misting before it cleared. It had rained the day before as well. Revere was preparing to set out on another ride, a much shorter ride than the earlier journeys, more pressing and less precise. He traveled light and bore no documents to support a message or directive—only his voice and what he knew. Revere had thirteen miles ahead of him on the first leg that night, maybe thirteen and a half. He might meet Dawes as he neared Lexington, he suspected. He would get to Adams and Hancock whatever the cost.

Revere stood for a moment on the muddy ground, the Old North Church tall across the river before him, the mare, Brown Beauty, shifting on her hooves. Revere understood that for himself and for the others who might ride on this night—along close wooded paths and over wet meadows to visit the farmhouses and boardinghouses and homesteads, to sound the warning and make the appeal—this was the most important horseback ride of his life. The Regulars were out. The Royal Army was on the move.