The last few years have seen a revival in campaigning for greater and deeper public access to the countryside. Thousands of people volunteer across the country to protect and improve public access – clearing vegetation, making more routes accessible for more people, and ‘fixing the fells’. A new generation of campaigners have joined the ranks of long-standing activists to seek, and to fight for, an expanded freedom to roam. Organisations like the Ramblers and the Right to Roam campaign want us to be able to explore more and have the opportunity to freely wander through woodland, along riversides, and over the grasslands of England.

Roaming freely, we are invited to step off the path, but the importance of these linear routes — of the ways old and new — mustn’t get lost in the noise and excitement of all these fresh possibilities. For many, if not most people, paths are the gateway to the outdoors. They provide certainty, direction, and the reassuring marks of walkers who have gone before. They facilitate access for those who are unable to clamber over gates and through uncertain ground, and they are physical guides in familiar and unfamiliar lands.

In 2017, I walked from Land’s End to John O’Groats. On this 1,550-mile wander, I discovered corners of the country — beautiful, wonderful, and odd corners — completely new to me; experienced landscapes which soothed and others which took my breath away, and the glorious satisfaction of a challenge met. What I wasn’t expecting, what took me by complete surprise, was that I would find beauty in the utility and form of the infrastructure itself — to fall in love with the hyperlocal path network, a spider’s web of history laid on the land.

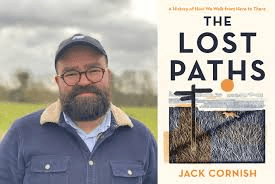

It is this history that I journey through in my book, The Lost Paths. Writing The Lost Paths allowed me to wander through so many parts of our island story — Saxon salt traders, the coming of the railways, the treatment of the Edwardian destitute, the eroding coast, and the preparation for Second World War invasion (to pick a few!). The paths of England and Wales — all 140,000 miles of them — hold our history. They burst with collective and individual memories.

But I wanted to write The Lost Paths not just so that I could share my love for our paths, but as a call to arms to save our lost paths. Because there could be as many as an additional 50,000 miles of paths which are unrecorded and unprotected. At the Ramblers, and at organisations like the British Horse Society and the Open Spaces Society, thousands of volunteers are working to uncover the stories of individual paths so that they can go back on the map for future generations of walkers, cyclists, and riders.

So, I hope you think about buying or borrowing The Lost Paths — but also getting involved in projects like Don’t Lose Your Way to reclaim our paths. In such a collective effort, we can be sure that, in the words of H. G. Wells: ‘There will be many footpaths in Utopia.’