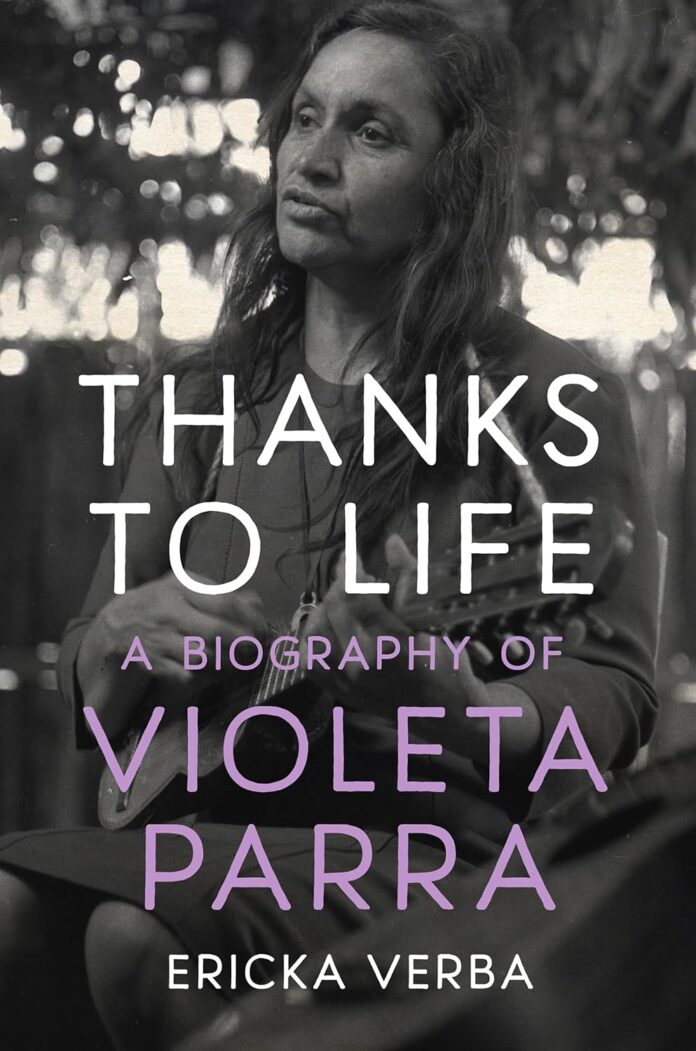

Ericka Verba’s book Thanks to Life: A Biography of Violeta Parra is the riveting culmination of a lifetime of dedicated and passionate research about the world-renowned Chilean artist Violeta Parra. Verba immerses readers into the rowdy Chilean peñas, elite Communist gatherings, smoke-filled Parisian nightclubs, and desolate circus tents to narrate decades of Chilean musical history through Parra’s life. Thanks to Life, a long-anticipatedbook for historians of Chilean music, reveals the tumultuous realities of Chilean women musicians through Violeta’s work and life.

Violeta Parra is considered the “mother of Chilean protest music,” who Verba positions as a multidimensional “everything-ist” skilled in songwriting, poetry, ceramics, and a range of visual arts. All but disregarded in Chile during her lifetime, Verba attributes Parra’s obscurity to gendered, racist and classist reasons. Verba frames such social characteristics around authenticity: Parra continually reinvented herself as “the representative of pure and unchanging traditions in the face of [modernity]” (p. 301). While authenticity is a concept that has been discussed almost ad nauseum in Folklore studies and Ethnomusicology, Verba masterfully revives the notion to demonstrate how Violeta manipulated this authenticity for her professional benefit. Parra deployed authenticity interchangeably as the Indigenous, the popular (of the people), the intuitive, or the ordinary, even as audiences and stakeholders stereotyped and at times denigrated her for the same reasons. Verba underscores the intersecting gendered and classist facets of such claims: Parra’s creative abilities, dress, and even her smell, both constructed her as authentic and marginalized her amongst urban audiences.

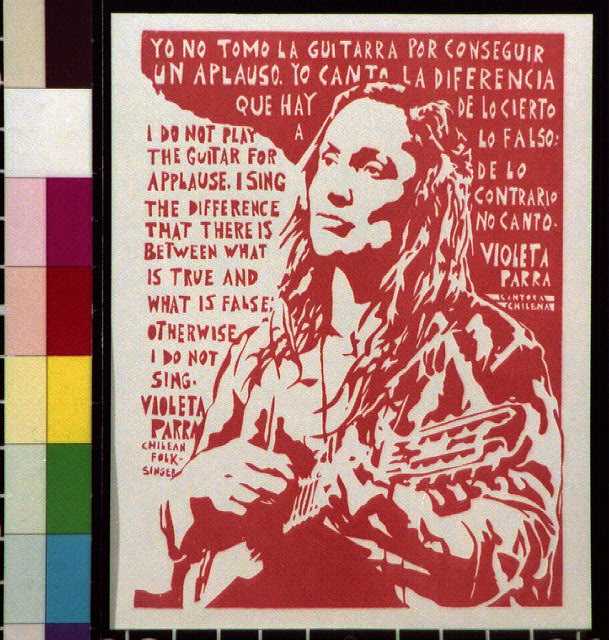

Source: Library of Congress

What I find most exhilarating about Thanks to Life is that Verba displays the complexity of Violeta for who she was, without attempts to either glorify or demonize her. Parra was notorious for her violent outbursts and brash personality; Verba reminds readers that had Violeta lived today, she would have likely been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Rather than attempting to explain Parra’s choices—her bawdy humor, toxic relationship with Gilbert Favre, or penchant for bashing guitars over others’ heads—she instead interrogates the gendered reactions to such behaviors. Readers come away with a vision of Violeta as determined, scrappy, and utterly nonconformist. [1] [2]

Methodologically, Verba pulls together primary sources from across the Americas and Europe by following the places where Parra travelled throughout her life. Through bringing in resources from unexpected places such as the American Folklife Center and the World Festival of Youth and Students Collection, she positions Parra’s story within broader currents of twentieth century folk movements and the cultural Cold War. While I have to admit that I hoped for oral histories rather than a heavy reliance on secondary sources, Verba selected poignant interpersonal and anecdotal details from the autobiographies of individuals such as Favre and Violeta’s brother, Nicanor, to bring Violeta’s story to life. Verba further incorporates song and poetry lyrics into each chapter to explain Parra’s political positions and supplement biographical information. The translations for such verses are particularly impressive as the poetry is riddled with colloquial phrases and Chilean-specific terminology. Collaborators Nancy Morris and Patricia Vilches did a stunning job translating while retaining meaning.

Thanks to Life is chronologically organized into ten chapters, with patterning reminiscent of the ten-line poet-songs that Parra composed. Chapter 1, “Materials,” explores Violeta’s childhood and adolescence in southern Chile, framed as the years that gave her the “‘materials that ma[d]e up [her] song’” (p. 11). Chapter 2, “Anti-Materials,” and Chapter 3, “Folklorista,” offer significant contributions to Chilean music history scholarship. In “Anti-Materials,” Verba reveals two decades of Parra’s life that current narratives, and Violeta herself, glossed over: her years making ends meet as a young working-class musician in Santiago. Years of gigging in nighttime dives disrupt Parra’s neat narrative of authenticity as a countryside child growing up to play folk music; yet, they explain how Parra gained the resiliency to maneuver within the male-dominated music industry in future years. “Folklorista” demonstrates the impact of her family, and particularly her siblings, on her initial success as a folklorista and her subsequent rise as a forerunner of the folk music revival. Her brother Nicanor was particularly influential in both introducing her to the intellectual and artistic circles of Santiago and inspiring her to begin composing the traditionally masculine poet-songs. Conversely, the breakup of the commercially oriented sister duo Las Hermanas Parra forced Violeta to strike out on her own career, leading her to the folk songs that would initially bring her individual fame.

Chapters 4, 7, and 8 document Parra’s two stints in Europe, first in the 1950s, and a decade later in the 1960s. Once again, Verba weaves Violeta’s personal life, and complex family dynamics, into the broader musical scenes and political landscapes. Of particular importance is the author’s exploration of how Parra rose from performing in working-class dives to exhibiting her artwork at the Louvre: Violeta revised her own narrative to exaggerate her poverty and Indigenous heritage, thereby elevating her authenticity as a folk “everything-ist.” Chapters 5 and 6, sandwiched between Parra’s Europe years, chronicle precisely these years spent back in Chile. Framed around Nicanor calling his sister “volcanic” (p. 121), Verba details the explosion of Violeta’s creative activities as she transitioned from folklorista to a multi-faceted songwriter and artist. The last two chapters, “New Songs” and “Last Songs,” hone in on key components of the final years of Parra’s life: her performances in her childrens’ folk club the Peña de los Parra; the composition of the songs that made her famous, including “Run Run se fue pa’l norte,” “Volver a los diecisiete,” and “Rin del angelito;” the ultimately unsuccessful Carpa de la Reina; and the singer’s deteriorating mental health.

As Verba remarks at the beginning of the book, Thanks to Life is not meant to be read alone, but rather to be accompanied with Parra’s music and images of her artwork. I personally recommend her tapestries (they brought me to tears the first time I saw them); Verba conveniently created a playlist for readers to listen to Parra’s music on her website.

I could not put the book down, even though I knew it would predictably end with Parra’s suicide. Over the pages, I became deeply invested not only in Violeta, but in her children Ángel and Isabel, her husbands and lovers, and the fate of Parra’s Carpa. While I have been a “Violetamaniac”for almost a decade, I learned new information on every page, especially as Verba connected Parra’s compositions to the context in which they were written. I laughed aloud when Verba highlighted Violeta’s humor through the story of a telegraph sent to God; I shared her anger when her first husband refused to support her artistic career. In short through this book, I feel that I know Violeta more deeply than I thought imaginable.

Hannah is a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Riverside and Visiting Instructor of Music at Occidental College. She holds an MA in ethnomusicology from UC Riverside and a BA in Music and Spanish from Messiah University. Sponsored by the Fulbright Hays and Fulbright IIE, Hannah’s current research examines the life and work of Chilean folklorist Margot Loyola and her impact on traditional music performance and education.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.