By Emma Louise Backe

In year marked by monumental legal cases against abusive men—Gisèle Pelicot in France, Cassie’s lawsuit against former partner Sean “Diddy” Combs—America re-elected a proud perpetrator of violence against women, who proceeded to fill his cabinet pick with others whose professional and personal histories are marked by allegations of abuse, sexual trafficking, and sexual assault. At the same time, a great deal of shows and movies throughout 2024 explored the dynamics of gendered violence, especially between intimate partners. The story of domestic violence in It Ends with Us was eclipsed by breathless media coverage of a potential feud between Justin Baldoni, the director, and Blake Lively, the producer and main star of the movie. Baby Reindeer adapted a real-life story of stalking and harassment into a dark comedy that nonetheless inverts traditional gendered depictions of victimization, and what forms of intimate entanglements we are willing to tolerate. Blink Twice takes aim at powerful CEOs, celebrities and men who complain about cancel culture in a story of drugs and rape that feels like a direct parallel to Diddy’s now infamous white parties. Even Joker: Folie à Deux attempts to rewrite the narrative by turning Harley Quinn—a victim of Joker’s abuse, manipulation and coercive control—into an instigator of the toxic, dare I say bad romance, driving Arthur deeper into a mental health spiral. Meanwhile Beetlejuice Beetlejuice resuscitates the story of a pedophile for a bit of nostalgia porn. Each of these attempt to grapple with different dimensions of gendered violence, with varying levels of success. Indeed, it’s the blind spots and missteps of these shows and movies, alongside the real-world headlines about the legal limitations and medical strictures placed on survivors, that reveal how much our understandings of abuse are still troubled by problematic stereotypes, victim blaming and misconceptions about when we are supposed to sympathize with or laugh at survivors.

In August, Blake Lively playfully invited the girls to wear their florals and see It Ends With Us, a movie adapted from the Colleen Hoover book of the same name. Audiences and media critics quickly picked up on the fact that Lively and director Justin Baldoni seemed to be advertising two very different movies. While Lively used the movie tour to promote her new hair care line, described the film as a fun romance, and facilitated publicity cross-overs with Deadpool & Wolverine, Baldoni spoke much more openly about the film’s themes of domestic violence and the necessity of addressing the subject matter with care and sensitivity (Hessekiel 2024). TikTok sleuths and other members of the media suspected a rift between Baldoni and Lively, although this speculation largely failed to connect to the film’s broader theme of intimate partner violence (IPV), or the risks of advertising a film about domestic violence (DV) without forewarning audience members. In December 2024, Lively went on to file a case of sexual harassment against Baldoni, including allegations of “improvised physical intimacy,” unwanted kissing and “personally added graphic content” instigated by Baldoni.

Although it’s slow to start, and certainly begins as a story of romance, the latter half of the film is a sobering depiction of domestic battery and gaslighting. Lively’s character—Lily Bloom—is thrown down the stairs, likely raped, and hit by her partner Ryle (played by Baldoni). Partial and fragmented scenes of violence do a good job of depicting both the neurological impacts of trauma and the ways that victims often strive to explain away or dismiss abuse perpetrated in the name of love. If you aren’t forewarned, however, these scenes are understandably difficult to watch especially for those audience members following Lively who might have thought they were seeing a rom com. This isn’t as simple as a playful bait and switch. Content depicting IPV can be triggering and risks retraumatizing survivors, especially for those who may initially identity with Lily Bloom, only to realize that they, too, might be abused. We know that one in three women in the world experience IPV in their lifetime (WHO 2021), although the number of survivors is likely much higher. That means that there is always a high likelihood of a handful of survivors—and secondary survivors, individuals who have witnessed abuse as children, or supported friends and family— in the audience, individuals who are owed a little more delicacy and support especially given the current climate of violence in the US. Without a trigger warning, and given the false advertising in the promotion of the film, It Ends With Us potentially (and very likely) harmed the very survivors it claimed to represent and celebrate.

For the noted faults behind its marketing, It Ends With Us does a good job of depicting the slow build of abuse, the red flags we are likely to misinterpret as romance, and the claustrophobic feeling of realizing that your partner means you harm. Despite Bloom’s fabulous privilege—her whiteness, her wealth, her beauty—she has almost no friends outside of her husband, Ryle, a form of social isolation that abusers often exploit to keep their partners dependent on them. Yet the film also stumbles at some crucial spots. When Bloom realizes that she is pregnant, likely as a result of Ryle’s rape, abortion is never mentioned. In a context where even rape and incest exceptions are being negated by Republican policy makers and abusers are filing lawsuits against their partners for seeking an abortion, the film’s failure to even consider a termination of pregnancy feels intentional. Reproductive coercion is often an overlooked aspect of IPV. We have many examples in conflict settings where women had to carry their pregnancies to term, and struggled with the maternal ambivalence of raising children of rape (Denov et al. 2018, Takševa 2017, Zraly et al. 2013). These instances of sexual violence and forced pregnancy have been codified into legal norms and protocols emphasizing the use of rape as a weapon of war.

Lily Bloom stoically accepts that she is pregnant and welcomes the arrival of her child, but in most circumstances this discovery would involve greater complications in navigating an abusive relationship. Women fear that if they leave abusive relationships, they could lose custody, or be charged as perpetrators for unintentionally exposing their children to violence. A growing body of research has also illustrated how abusive men will use cultural expectations of the good and self-sacrificing mother to force her to stay (Dekel and Abrahams 2023, Heward-Belle 2017, Kruger 2019), sometimes using their children as an abuse tactic (Sullivan et al. 2023, UNGA 2023). Rather than wading into the complicated, but nonetheless crucial political valences of motherhood and IPV, It Ends With Us decided to avoid the conversation entirely, a choice that only reiterates the privilege of Lively’s character. At the end of the film, when she asks Ryle for a divorce, he agrees fairly quickly. He quite simply walks away. This too is an entirely fantastical and frankly dangerous representation of domestic violence. We know that Republicans are working to overturn No Fault Divorce, which makes it easier for survivors of domestic violence to exit their abusive relationships. Indeed, women are more likely to be killed by their abusive partner (Kelly 2024) or face incarceration (Goodwin 2020, Heffernan 2024) than to be met kindly by the criminal justice system. Survivors who are economically dependent on their partners, especially if they share children, often fear leaving, especially with such minimal financial and social support available to survivors (see also Davis 2006, Bloom 2024, Sweet 2021). Women are often asked why they don’t simply “leave.” It Ends With Us only furthers the narrative that abusive partners will simply release their victims, and that divorce is a seemingly simple and straightforward legal process.

The mixed messaging of the It Ends with Us press tour became even more garbled as Lively repeatedly showcased her partner Ryan Reynolds and Hugh Jackman, in a Deadpool & Wolverine cross over that no one asked for. The Deadpool franchise is intentionally irreverent, leaning into trolling both the right and the left for the lulz. This approach has been used to excuse any humor in poor taste, a tactic traditionally employed by internet trolls. But the series has also been dogged by allegations of abuse against T.J. Miller, who played Wade Wilson’s friend in the first film. Miller was not recast in the subsequent films. But that didn’t stop the franchise from continuing to make jokes about sexual violence. There is a stark difference between playfully showcasing Wade’s sexual fluidity and openness—an aspect of queerness that was used in the advertising for Deadpool & Wolverine—and using sexual violence as a punchline. In a post-credit scene of the film, Chris Evans as the Human Torch goes on a long and frankly unfunny screed in which he jokes about killing and raping Cassandra Nova, the main baddie, who he refers to as a human “fuck box.” The scene is supposed to destabilize and poke fun at the squeaky clean persona of Captain America (also played by Evans in the Marvel Universe), but just decides to punch down by making sexual violence and female homicide the butt of a bad joke. I’m not a comedy writer but I’m confident I could have thought of a multitude of other takes that didn’t rely on the brutalization of a woman’s body to prove the movie’s purported “edginess.” The joke just reveals how little the lessons of MeToo and the debates over the use of sexual violence to “drive narrative” in shows like Game of Thrones were internalized, if the men in Hollywood were even listening at all. As long as “it’s just a joke” is used as a convenient excuse, we can keep making light of rape, an approach that’s constitutive of a larger problem of rape culture. We simply do not take it seriously.

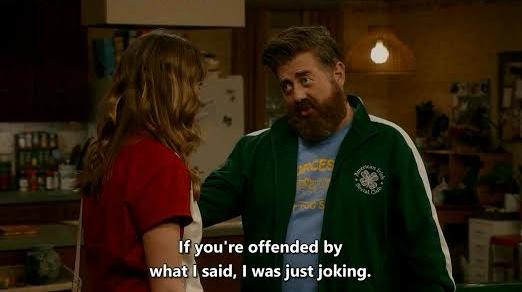

Indeed, 2012 was dubbed the “year of the rape joke” (Romano 2012), sparked by a comment comedian Daniel Tosh made during one of his stand-up sets. Since then, there’s been a great deal of analysis about the relationship between rape jokes, media ecosystems, and how humor works in concert with normalizing and minimizing sexism, misogyny, patriarchy, and violence against women (Ford et al. 2008, Montemurro 2003, Romero-Sánchez et al. 2010, Ryan et al. 1998, Tomae and Viki 2013). As Lockyer and Savigny argue, “Media coverage which repeats jokes told by male comedians encourages an audience response to this ‘ironic’ manner. That men who make rape jokes are given space to defend their actions and offer apologies, simply reinforces the sense that male sexual violence towards women is something that is a legitimate topic of humor, rather than something we as a society should be seriously addressing” (2020:444). Those who might push back against rape jokes are labeled as being too sensitive, or lacking a sense of humor, with the “jokesters” falling back on the excuse that it was just a joke and that people should not, therefore, take their words seriously (Kramer 2011). But research shows that exposure to this kind of humor only serves to reinforce the sexual objectification and violation of women, while normalizing and increasing tolerance of gendered violence (Pérez and Greene 2016). In Lauren Bates’s book Men Who Hate Women, a chapter is dedicated to high school students vulnerable to the men’s rights activist (MRA) pipeline that inevitably leads to people like Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate. She notes that “these young boys are accessing part of the manosphere through memes and jokes, often at the expense of women […] These children aren’t necessarily even aware of specific manosphere communities, but nonetheless absorb aspects of their ideology, packaged in easily digestible and highly memorable memes and jokes, or made palatable and respectable for mainstream consumption by prominent media figures” (2011:275). Images depicting women being beaten up are tagged with #freshmemes and #edgymemesforedgyteens, leading some to then make jokes about rape and femicide in the classroom. Humor is being used as a tool to redpill young men, all while spreading misinformation about false rape accusations and the dangers of catfishing.

This strategy of minimization and normalization is also reinforced by media representations of gendered violence. Instances of femicide are described in softer language like “domestic disputes” or “love killing” (Schnepf and Christman 2023), or minimized, like the Netflix show on domestic abuse titled Worst Ex Ever. Or, in the case of South Africa, and other parts of the Global South, media discussions of GBV only reinforce racialized and dehumanizing depictions of the violent “Other” (Boonzaier 2022, Boonzaier 2017). These representations turn intimate partner violence and domestic homicide into the juicy fare for tabloids or made-for-TV movies to slake the thirst of True Crime fans, rather than explicitly naming the violence. An expose on Cormac McCarthy’s “secret muse” in Vanity Fair is actually a story about how the author groomed a 16-year old girl into a sexual relationship. These are all forms of “elliptical speech” (Ross 2010), or the ways that we have learned to talk around gender-based violence, avoiding the tough conversations while undermining its harms for those who may or may not survive. For instance, after New York extended the statute of limitations, Cassie was able to file a lawsuit against Diddy, an action that was quickly followed by additional allegations and investigations of Diddy’s longstanding history of violence. Yet in media coverage on the case, many outlets instead decided to focus on the copious bottles of lube discovered at Diddy’s mansion and joke about his infamous “freak off parties,” rather than explicitly name the violence embedded within these object lessons. The Diddy story was framed as a story about sex, drugs and scandal typical of a celebrity rather than what it was—a violent perpetrator who drugged and raped his victims, some of whom were not even the age of consent. It’s hard to say whether the squeamishness of the media had to do with content restrictions or a more generalized but nevertheless pernicious disinterest in straightforwardly addressing a story of sexual violence.

Similarly, when Matt Gaetz was nominated by Trump, allegations of human trafficking resurfaced, only for the media to proceed to make jokes about pedophilia and rape. In one segment from The Daily Show, Jon Stewart delightfully imagined a scene of prison rape between Gaetz and the Hamburglar, as if the only way to deal with an alleged rapist is to make a joke about prison rape. Because, you know, the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun. These jokes, as it turns out folks, don’t write themselves. Instead they are part of a patent inability to respond sensitively to gender based violence—social discomfort instead has to be constantly couched in jokes that only serve to further alienate survivors and make light of their harm.

Todd Philip’s sequel Joker: Folie à Deux seemed to be an attempt to correct the celebration of the first movie’s wanton use of sexual violence and stalking. The Joker film was celebrated amongst men’s rights activists and incels, much to the apparent shock and dismay of director Todd Philips, even though historically Joker has always been an abuser. As I’ve covered before, The Killing Joke heavily implies that Joker shot, paralyzed and raped Barbara Gordon. His romance with Harley Quinn throughout the comic books and television series is entirely based on abusive control. And yet when Birds of Prey (2020) was released, celebrating the emancipation of Harley Quinn from her relationship with the Joker, it was review bombed and buried in the DC filmography.

In Folie à Deux, Phillips introduces us to a different version of Harley Quinn. Rather than Joker’s psychologist, she is a fellow inmate who we learn is obsessed with the figure of the Joker (though not necessarily the man behind the makeup) and voluntarily commits herself to get closer to him. Phillips decides to turn Harley (Lady Gaga) into an instigator of Joker. In a co-dependent toxic relationship, she urges Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) to stop taking his meds, to lean harder into his Joker persona even as his lawyer advises otherwise. Arthur becomes enraptured. The story of abuse here is rewritten—Harley is not a victim but a perpetrator, a manipulator, a clout chaser who is pursuing the fantasy of Joker to the peril of Arthur Fleck. It’s not only retconning the story of Harley and Joker, it’s playing into the dangerous narratives that also circulated during the Depp and Heard trial, the allegations of defamation that Marilyn Manson brought against Evan Rachel Wood. Abusive men pass themselves off as the real victims exploited by dangerous women—the trope of the femme fatale—who have somehow fabricated their entire story of abuse for celebrity status. Because evidently every woman wants their names to be associated with horrific acts of violation, and to shell out exorbitant legal fees in order to be cross-examined in front of their perpetrators. Which is not to say that men aren’t victims of GBV—but as the spectacle of the Depp vs. Heard trial illustrated, the public is far more interested in defending an abuser than considering why women might remain in abusive relationships.

Indeed, longtime friend and collaborator with Johnny Depp, Tim Burton, used 2024 to resurrect Beetlejuice in yet another bid for nostalgia porn. Despite the cult classic status associated with the first film, most people forget that it’s a story about forced child marriage. Beetlejuice is a sleazy fraudster who is romantically and sexually interested in a child, Lydia Deetz (Winona Ryder); and repeatedly gropes Gina Davis’s character for laughs. Rather than contend with the problematic politics of Beetlejuice, Burton simply recapitulates the same narrative. Despite the fact that adult Lydia is evidently traumatized by her encounters with Beetlejuice as a child, Burton forces her to team up with Beetlejuice again and get married to save her daughter. As if this weren’t enough, Lydia both experiences and dreams about giving birth to a little Beetlejuice, suggesting that she too is forced to carry a child of rape. The horrifying appearance of the baby, and its uncanny resemblance to Beetlejuice is supposed to elicit an uncomfortable combination of disgust and mirth, such that we are yet again distracted from the import of the child. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice even makes a joke about how “the juice is loose,” a reference to OJ Simpson who famously abused his wife Nicole Brown for years, and likely killed her. We use humor about sexual violence to continuously undermine and distract from its trauma and its consequences.

Blink Twice and Baby Reindeer employ humor much more intentionally. In Netflix’s Baby Reindeer, struggling comedian Donny Dunn (Richard Gadd) entertains the attention of Martha in part because she’s one of the few people to laugh at his jokes. What begins as a playful exchange at a bar however escalates into Martha stalking and harassing Donny. Her strangeness, her size, her wild laugh, and the absurdity of her sexual innuendo sit alongside the severity of her behavior and Donny’s growing fear as he realizes that the situation is deadly serious. His fellow coworkers at the bar even joke about his relationship with Martha. Donny is uncertain about whether to join in and continue to make light of his situation. He doesn’t want to feel emasculated by this brash and big woman, especially as he hides his trans girlfriend across town. When we get flashbacks of Donny’s life, we also see how Darrien, a TV writer, uses promises of a comedy career to drug and sexually assault Donny. Humor essentially serves as a dangerous trap that keeps Donny in a cycle of violence, while placing bystanders at a distance. If Donny is laughing along with his own abuse, then surely there’s nothing to worry about.

Zoë Kravitz’s Blink Twice similarly starts off as a light comedy, the early tones of the movie used to distract the audience from the otherwise terrifying conceit of the film—flying to a private island to party with a disgraced tech CEO Slater King (Channing Tatum) because the main character, Frida (Naomi Ackie), has a crush on him. Quite early, friends Frida and Jess even share a joke about the possibility of a human sacrifice. It’s not clear how long Frida and Jess stay, but their nights are full of drinking, drugs, white dresses (hey Diddy) and debauchery, evenings that seems delightfully unhinged and full of mirth. But the party haze starts to fade when memories and people start to disappear—first Jess vanishes and then the women say they can’t recall her at all. Frida tries to find Jess, only to start recalling other parts of their stay that she had blacked out. As it turns out, Slater has been using snake poison to drug all the women, who are repeatedly assaulted and violated by the men in the villa each night, only for their memories to be wiped clean by morning and the partying to recommence. The worse the trauma, the more women apparently forget. Frida shares this revelation with fellow party goer Sarah and they hatch a plan. But the only way to survive is to continue to play along with the illusion that they are having a good time. Just keep smiling, Frida tells her, the pained smiling forcing a prick of tears. The dedicated commitment to ignoring the violation of women is the only way that Frida and Sarah are able to escape alive.

Frida takes her revenge by drugging Slater with the very snake venom he weaponized against her and taking over his tech empire, but this is a bitter pill to swallow. Others have taken different routes to justice. When Gisèle Pelicot discovered that the husband had spent years surreptitiously drugging and raping her, pimping out her body to other men for a price, she demanded that video evidence be shown in court in an open trial. The defendant’s lawyer initially smeared her as an alcoholic and an accomplice to her husband. “I have the impression that the culprit is me, and that behind me the 50 are victims,” she said during initial testimony in September 2024 (Talmazan 2024). Gisèle bravely opted for the graphic videos documenting her repeated assault to be shown within the courtroom, arguing that, “I don’t want them to feel ashamed anymore. It’s not for us to feel shame — it’s for them [sexual attackers] […] Above all, I’m expressing my will and determination to change this society” (Andrews 2024). This shame is part and parcel of the culture in which rape jokes are acceptable, and treated as both harmless and humorous. The butt of the joke is always the victim, whose violation is instead used as a source of mockery. As Lou Marie Kruger writes, “The person who has been shamed can be thought of as having been killed psychologically. The self has died. People are psychologically killed (their humanity is taken away) if they are being treated with contempt or disrespect, as though they are unimportant or insignificant.” (2019:67). Indeed, without sufficient recourse through the criminal justice system, or social support structures, shame and self-hatred can spiral into negative coping mechanisms, self-harm and suicide. Roxanne Gay has discussed how she used over-eating as a coping mechanism after her rape, hoping to “protect” herself from sexualization. I still remember Daisy Coleman, the sexual assault victim whose story was depicted in the documentary Audrie & Daisy (2016), and who died by her own hand in 2020. Many speculated that her assault, and the bullying she suffered as a result of the documentary, contributed to her suicide.

Other films and shows have managed to be funny without punching down at survivors. Bad Sisters, an Irish dark comedy, explores an abusive relationship without ever making light of Grace, its titular victim and surrounds her with a gaggle of sisters willing to defend her against violence, whether it’s perpetrated by her husband, the prison industrial complex or insurance companies. Sex Education has an entire storyline dedicated to Aimee’s experience of unwanted sexual contact on her bus to school in Season 2. The show never skimps on lighthearted moments but knows when to reel it back when considering Aimee’s story, and her understandable avoidance of buses and even sex with her boyfriend following the encounter. Kevin Can F**k Himself uses the horrifying depiction of heterosexual marriage and weaponized incompetence in sitcoms to tell a much darker story about how abusive men might drive their partners to consider violence or even self-harm. The stark tonal juxtaposition between Kevin’s storyline, and that of Allison, his wife, whose growing claustrophobia within the relationship ultimately leads her to fake her own death, ultimately converge in the final season, when Kevin burns her passport. Although the house, too, goes up in flames, we see how all of Kevin’s casual jokes about arson are not, in fact, harmless or inconsequential to those around him. These shows, among others, demonstrate that comedies can include an honest discussion of gendered violence; so long as they don’t diminish the significant harms associated with GBV and the fact that there remain minimal support systems for survivors.

As Gisèle Pelicot declared during the trial of her husband and the 50 men who raped her, “Shame has to switch sides.” But this cultural and political transition should not have to rely on survivors sharing their stories over and over again, especially when they are often met with crude jokes, memes, and allegations that they are exaggerating or “making it up.” Even a seemingly benign question—if a woman found herself unarmed in the woods, would she rather confront a man or a bear—turned into a much wider debate about the violence of patriarchy. Men were baffled as to why women would jokingly prefer the bear, highlighting how even this playful thought experiment about women’s safety could be met with male anger and resentment. Laughter at survivors’ expense continues to shame victims into silence, forcing themselves to smile even as they are questioned why they didn’t fight back harder, why they didn’t scream louder. Because after all, if everyone’s smiling, that means it’s consensual, right? Or rather, it’s how you manufacture consent.

Works Cited

Bates, Lauren. 2021. Men Who Hate Women: From Incels to Pickup Artists, The Truth About Extreme Misogyny and How It Affects Us All. Sourcebooks.

Bloom, Allison. 2023. Violence Never Heals: The Lifelong Effects of Intimate Partner Violence for Immigrant Women. New York: NYU Press.

Boonzaier, Floretta. 2017. “The Life and Death of Anene Booysen: Colonial Discourse, Gender-based Violence and Media Representations.” South African Journal of Psychology 47:470-481.

Boonzaier, Floretta. 2022. “Spectacularizing Narratives on Femicide in South Africa: A Decolonial Feminist Analysis.” Current Sociology 71:78–96.

Davis, Dána-Ain. 2006. Battered Black Women and Welfare Reform: Between a Rock And a Hard Place. State University of New York Press.

Dekel, Bianca and Naeemah Abrahams. 2023. “‘I’m not the mother I wanted to be’: Understanding the increased responsibility, decreased control, and double level of intentionality, experienced by abused mothers.” PLoS One 18(6):e0287749.

Denov, Myriam, Amber Green, Atim Angela Lakor and Janet Arach. 2018. “Mothering in the Aftermath of Forced Marriage and Wartime Rape: The Complexities of Motherhood in Postwar Northern Uganda.” Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement 9(1).

Ford, Thomas E., Erin R. Wentzel, and Joli Lorion. 2001. “Effects of Exposure to Sexist Humor on Perceptions of Normative Tolerance of Sexism.” European Journal of Social Psychology 31(6):677–691.

Goodmark, Leigh. 2023. Imperfect Victims: Criminalized Survivors and the Promise of Abolition Feminism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goodwin, Michele. 2020. Policing the Women: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heward-Belle, Susan. 2017. “Exploiting the ‘Good Mother’ as a Tactic of Coercive Control: Domestically Violent Men’s Assaults on Women as Mothers.” Affilia 32:374–389.

Kramer, Elise. 2011. “The Playful is Political: The Metapragmatics of Internet Rape-Joke Arguments.” Language in Society 40(2):137–168.

Kruger, Lou Marie. 2019. “Of Violence and Intimacy: the Shame of Loving and Being Loved.” The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence III(1).

Kruger, Lou Marie. 2019. Of Motherhood and Melancholia: Notebook of a Psycho-ethnographer. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Lockyer, Sharon and Heather Savigny. 2020. “Rape jokes aren’t funny: the mainstreaming of rape jokes in contemporary newspaper discourse.” Feminist Media Studies 20(3): 434-449.

Pérez, Raúl and Viveca S. Greene. 2016. “Debating rape jokes vs. rape culture: framing and counter-framing misogynistic comedy.” Social Semiotics 26(3):265-282.

Montemurro, Beth. 2003. “Not a Laughing Matter: Sexual Harassment as ‘Material’ on Workplace-Based Situation Comedies.” Sex Roles 48(9/10):433–445.

Romero-Sánchez, Monica, Mercedes Durán, Hugo Carretero-Dios, Jesus L. Megiás, and Moya Miguel. 2010. “Exposure to Sexist Humor and Rape Proclivity: The Moderator Effect of Aversiveness Ratings.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 25(12):2339–2350

Ryan, Kathryn M. and Jeanne Kanjorski. 1998. “The Enjoyment of Sexist Humor, Rape Attitudes, and Relationship Aggression in College Students.” Sex Roles 38 (9/10):743–756.

Schnepf, Julia and Ursula Christmann. 2023. “’Domestic Drama,’ ‘Love Killing,’ or ‘Murder’: Does the Framing of Femicides Affect Readers’ Emotional and Cognitive Responses to the Crime?” Violence Against Women 30(10).

Sullivan, Cris, Mackenzie Sprecher, Mayra Guerrero, Aileen Fernandez and Cortney Simmons. 2022. “The Use of Children as a Tactic of Intimate Partner Violence and its Impact on Survivors’ Mental Health and Well-being Over Time.” Journal of Family Violence 39:53–163.

Sweet, Paige. 2021. The Politics of Surviving: How Women Navigate Domestic Violence and Its Aftermath. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Takševa, Tatjana. 2017. “Mother Love, Maternal Ambivalence, and the Possibility of Empowered Mothering.” Hypatia 32(1):152-168.

Thomae, M. and G.T. Viki. 2013. “Why did the woman cross the road? The effect of sexist humor on men’s rape proclivity.” Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology 7(3):250–269.

United Nations General Assembly. 2023. “Custody, violence against women and violence against children.” Human Rights Council Fifty-third session, Agenda Item 3. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G23/070/18/PDF/G2307018.pdf?OpenElement

World Health Organization. 2021. “Devastatingly pervasive: 1 in 3 women globally experience violence.” https://www.who.int/news/item/09-03-2021-devastatingly-pervasive-1-in-3-women-globally-experience-violence

Zraly, Maggie, Rubin, Sarah E. and Donatilla Mukamana. 2013. “Motherhood and Resilience among Rwandan Genocide-Rape Survivors.” Ethos 41:411-439.