By Nancy Spannaus

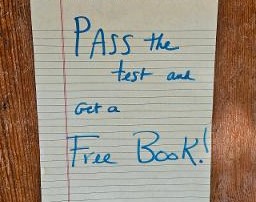

May 25, 2025—“Pass the test and get a free book,” read the sign I put up on my table at the Gaithersburg Book Festival last week. The test was to recite the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution. “I bet you no one will be able to do it,” declared my husband when I told him what I intended to do to attract potential readers.

Unfortunately, he was right. At least a couple dozen people came up to ask about the test, and the most common response was, “Oh, I can’t do that.” Of those who tried, two young women came very close, aided by their memory of the lyrics from the 1970s musical School House Rock. Those lyrics omit a significant phrase, among other things – and the women also mixed up some verbs. I gave them a discount, but not the full prize.

This was an instructive experiment. Only two individuals had actually had to memorize the Preamble text for school. Many were abashed for their failure and implicitly acknowledged that this was something they should know. They gladly listened to me recite the inspiring words:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ensure Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States.

A Disturbing Response

One disturbing response came from a middle-aged woman, probably a teacher, who said she got pushback from young people on the inclusion of the phrase “promote the general Welfare.” That can’t be right, they told her; we don’t believe in “welfare.”

Have we really come so far from the Founders’ original conception of our government’s purpose as to disclaim the idea of the “general welfare?” Not only is this phrase carried over from the Articles of Confederation, but it is also the only purpose which appears twice in our founding document – once in the Preamble and once again in the beginning of Article I, Section 8 on the powers of Congress. Its inclusion underscores our Founders’ understanding that the liberties and prosperity of our nation depend on a combination of personal freedoms and consideration for the welfare of our fellow citizens, not simply your personal rights.

The need for a “liberal” interpretation of the general Welfare was underscored by the statesman Alexander Hamilton in his Opinion on the Constitutionality of the National Bank.[1] Indeed it lies at the heart of our concept of republican government.

I strongly suspect that the objections that this woman reported to me are widespread in our society today. They are reflected in the fact that so many people think of our Constitution in terms of the Bill of Rights, rather than its broader purposes, turning it and the Declaration of Independence into libertarian documents. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. (For more, see From Subject to Citizen: What Americans Need to Know about Their Revolution. Click here. )

Let’s look further into the genesis of the Preamble.

The Preamble

Today is the anniversary of the commencement of the U.S. Constitutional Convention – May 25, 1787 – when a quorum of specially chosen delegates arrived in Philadelphia to overhaul the Articles of Confederation. Over the course of the next four months, the attendees hammered out a framework for self-government comprised of 73 different articles.

To craft this unwieldy text into final form, the delegates set up a special Committee on Style and Arrangement on September 7. It was comprised of Alexander Hamilton (New York), William Samuel Johnson (Connecticut-chair), Rufus King (Massachusetts), Gouverneur Morris (Pennsylvania), and James Madison (Virginia). It took them three days to do their job.

The original preamble which they were handed was quite different from one the Committee drafted, and the delegates ratified. It read:

We the People of the states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia do ordain, declare, and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.

Clearly the Committee – dominated by nationalists like Morris, Hamilton, Madison, and King – thought a more inspirational opening was needed, one that would lay out clearly the objectives of the government they were forming. Gouverneur Morris is considered to have been the leading author. He had been one of the most voluble participants in the Convention, including in opposition to tolerating slavery. Yet the voting record shows no dissent over the choice of members of the Committee (including the controversial Hamilton), nor significant debate or controversy over the completed text.

Lofty Goals

As finalized, the Preamble defines the goals of the new government, which the enumerated powers that follow are supposed to realize. These goals have not generally been considered to have the force of law, but subsequent laws are expected to be coherent with this foundation.

That said, the specific objectives are worth examining in more detail.

First, a comparison with the Articles of Confederation.[2] That document, ratified in 1781, contained no overall statement of purpose, but included three of the goals outlined in the later Constitutional Preamble: “common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare.” It also stated that the “delegates of the United States of America in Congress” committed themselves to a “perpetual Union between the states” (then listed individually).

The first major change then, as noted angrily by the Constitution’s opponents like Patrick Henry, was the substitution of “We the People of the United States” for the “delegates.” The change emphasizes, as did leading statesmen like Supreme Court Justice John Marshall later, that the Constitution was the product of the “people,” not of the states. Special conventions of the people were elected to discuss ratification, side-stepping established state institutions (the legislatures). Broad public discussion ensued over a period of nearly 10 months to produce this governing document.

The second major change was the addition of two more goals: establishing justice and ensuring domestic tranquility. A Congressional analysis[3] of the historical background of the Preamble argues that these additions grew directly out of problems during the Confederation period, when state governments were engaged in denying equal rights (justice) to some of its citizens,[4] and unrest both within and between states was rampant (preventing tranquility).

The third major change from the Confederation, and most Constitutions in the world, was the pledge to ensure the Blessings of Liberty “for Ourselves and our Posterity.” In other words, the Constitution was intended to provide its benefits for future generations, not just for the current population. Such a commitment demands that legislators, who take an oath to uphold and defend the Constitution (NOT an individual), craft their legislation and policies with the future consequences in mind.

Unlike Thomas Jefferson, who thought that the Constitution should be revised every 20 years or so, the Framers looked toward a stable framework that would last for generations. They carefully avoided giving priority to any of the three branches of government or its incumbents, in favor of a clear written framework for achieving certain goals.

There’s More to It

Controversy continues to rage over the merits and demerits of the Constitution to this very day, of course. Most of it centers on its treatment of slavery and the extent of national power over the states, with far different views expressed on different sides of the political spectrum. With such divisions on our founding document, how can we expect to achieve national unity?

The first step which I recommend is for more citizens to take the reasoned, historical approach. To that end, I have written the book From Subject to Citizen: What Americans Need to Know about Their Revolution, which challenges people to understand our Revolution in more depth. Memorizing the Preamble is not the goal: understanding its genesis and intent are.

[1] See this post on Hamilton’s paper.

[2] For the full text of the Articles, click here.

[3] Click here for this analysis.

[4] Of course, most states continued to deny citizenship rights to women and Blacks for many decades more. In that sense, the Constitution’s Preamble, like the Declaration, was what Martin Luther King called a “promissory note” for huge numbers of Americans.

Related Posts

Tags: Constitution, General Welfare, Nancy Spannaus, Preamble, U.S. Constitution