Toward the Celebration of the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution

By Nancy Spannaus

Jan. 12, 2025—There are many milestones toward the declaration of American Independence in the year 1775, ranging from the outbreak of fighting at Lexington and Concord in April, to the founding of the American Continental Army in June, and the de facto establishment of revolutionary governments replacing the Crown’s power in most colonies.[1] But the one I want to focus on here is one lesser known, but critical to understanding the nature of our Revolution.

In April 1775, the Americans took the international lead against slavery by establishing the first formal anti-slavery organization ever recorded. The founder of that organization was Anthony Benezet, a Quaker in Philadelphia who had been educating Blacks (enslaved and free) and publishing tracts against slavery from the 1750s forward. Its name was the Pennsylvania Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

Far from being an anomaly, this event reflected the fact that the movement to abolish slavery in the American colonies was an integral part of the American revolutionary upsurge.[2] All the colonies but Georgia had joined the Continental Association established by the first Continental Congress in October of 1774, and pledged to abide by a cessation of the slave trade. This action was widely seen at the time to be a step toward the abolition of slavery itself. Pamphlets, speeches, and even local resolutions attacking the “wicked cruel and unnatural Trade”[3] circulated throughout the colonies, and although they attracted a minority, their number of adherents was expanding. Manumissions were increasing rapidly.

The fact that this burgeoning movement, which grew substantially over the next 20 years, did not succeed, is generally used to denigrate, or even deny, the significance of Americans’ early anti-slavery sentiment and action. Some today have even gone so far as to claim that Great Britain was far ahead of our nation in opposing the odious practice, despite the fact that the first anti-slave trade society in England was not established until 1787,[4] and that the British Empire was the primary support for the international slave trade up through the U.S. Civil War.

In the rest of this post, I provide a further picture of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and an additional sketch of the actions against slavery in the other colonies during the 1770s and ’80s. A more thorough treatment is available in my 2023 book, Defeating Slavery: Hamilton’s American System Showed the Way.

First, Let’s Introduce Anthony Benezet

As his name suggests, Anthony Benezet’s origins are in France (born 1713). His family being Huguenot, and subject to persecution in that country, they moved to England, and then ultimately to Philadelphia in 1731, where Benezet became a Quaker and a schoolmaster, teaching both Black and white students under Quaker auspices.

By the end of the 1750s, Benezet began an active, extensive career as an abolitionist writer. His first tract was entitled “Observations on the Enslaving, Importing and Purchasing of Negroes.” It attacked the slave trade as “inconsistent with the gospel of Christ, contrary to natural justice, the common feelings of humanity, and productive of infinite calamities to many thousand families… and consequently offensive to God….”[5]

Many more tracts followed, including refutations of the canard that African society was so degraded that slavery in a “Christian” society would be a blessing, through a description of African countries like Guinea. His 1762 piece entitled A Short Account of that Part of Africa Inhabited by the Negroes circulated internationally and was republished in England in 1768.

Benezet’s most influential writing came in 1766, and was entitled A Caution and Warning to Great Britain and Her Colonies, In a Short Representation of the Calamitous State of the Enslaved Negroes in the British Dominions. In this piece, Benezet took evidence he had accumulated from interviewing slave ship captains and others, to present in graphic detail the horrors of the slave trade, the barbaric treatment of the enslaved, and the massive extent of the mayhem, both in Africa and on the slave plantations. While blasting the British authorities, Benezet did not hesitate to excoriate the American “lovers of liberty” who participated in this mass murder. To ensure the pamphlet was read in Great Britain, he instructed his Quaker friends to print 2000 copies and get one to every member of Parliament. The tract was also widely read in the United States; it went through at least five printings.

But Benezet was not only a propagandist against slavery and a teacher; he was what you might call a political organizer on an international scale. His close relationship with Benjamin Franklin helped in this regard, as Franklin had established an impressive network of collaborators and supporters of American independence in both the British Isles and France. But it is Benezet who deserves recognition as the leader of a transatlantic abolition movement; thanks to him, America set the example for others, and catalyzed them into action.

The Pennsylvania Abolition Society

On April 14, 1775, Benezet called together a small group at the Rising Sun Tavern in Philadelphia. The initial society consisted of 10 individuals who were primarily Quakers. (The group included non-Quaker Thomas Paine.) It called itself The Pennsylvania Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. The society cut its teeth by taking on the case of a woman who was attempting to stop her sale to a Virginia master, by claiming she was free by virtue of being of native American blood. The group was ultimately successful in manumitting her, and thus established its reputation as an aid to those being kidnapped into slavery.

The escalation of the war interfered with the Society’s activities, and they had only four meetings before becoming inactive. However, in conjunction with the Quakers, politician George Bryan, and Thomas Paine, the Society undoubtedly had a major impact in helping push through Pennsylvania’s 1780 legislation for the gradual elimination of slavery, an international milestone. The act declared the broad commitment: “We conceive that it is our duty, and we rejoice that it is in our power, to extend a portion of that freedom to others, which hath been extended to us.”[6]

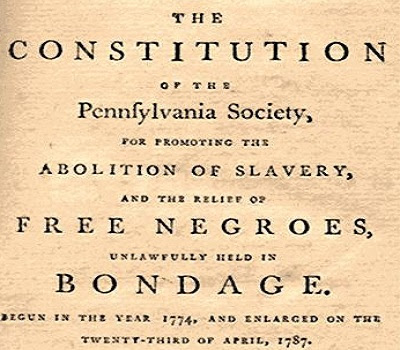

In February 1784, the Society reorganized, changing its name to The Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage (known from then on as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, or PAS); 18 individuals attended the founding meeting. Benezet died three months later, but the Society quadrupled in size over the next two years and began to reach more and more non-Quakers.

In 1787 the group re-organized again, this time attracting nationally known political figures such as Benjamin Rush and Benjamin Franklin. According to an article on the site of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the PAS had three foci: “first, agitating against slavery in the political realm; second, aiding kidnapped free blacks and, where possible, fugitive slaves in courts of law; and third, establishing education for, and financial support to, free communities of color.”[7]

The PAS is best known for its sponsorship of a 1790 petition to the U.S. Congress, submitted by its President Benjamin Franklin, which urged the abolition of slavery. That petition was shelved, but it was just beginning of an active campaign of petitioning public officials to take action against the slave trade, to provide legal aid to endangered Blacks, to improve conditions for Blacks, and to establish educational institutions for Black citizens. Pennsylvania became known as a Mecca for escaping slaves, as well as a center for their education.

In conjunction with societies in other states, and the American Convention of Abolition Societies (established 1794), the PAS continued to expand its activities, despite opposition, over the next three decades. While not including Blacks in the Society, nor establishing integrated institutions, the Society provided invaluable aid to the Black Community in its fight for full citizenship, education, and a better life.

Major credit should go to Anthony Benezet.

A Brief Overview of the Context

While Pennsylvania was the colony where the first organized abolitionist society was founded, it was by no means the only one where abolition sentiment and activity were growing along with the revolutionary ferment against Great Britain’s oppression.

Beginning at the time of the 1765 Stamp Act revolt, slavery and the slave trade became a frequent target of the American colonists. Threats to impose huge taxes on the trade, or to outlaw it all together (Massachusetts), had resulted in British government vetoes, but had not stopped the agitation. The agitation got a significant boost in early 1772 with two widely publicized events: the publication of the poetry of the enslaved Phillis Wheatley, and the Somerset decision. The Wheatley case eviscerated the argument that Blacks had inferior intellects, and the Somerset decision, in which British leading jurist Blackstone freed a slave whose master had taken him to England and was trying to re-enslave him, was widely interpreted (wrongly) as declaring slavery illegal in the British Empire.

These actions spurred free and enslaved Blacks in the American colonies to use the right of petition and, where possible, the power of the courts, to try to gain freedom or eliminate slavery altogether. These actions were particularly numerous in Massachusetts, and often successful.

Slavery was also targeted in the First Continental Congress (Sept.-Oct., 1774), where the delegates swore not to participate in the trade with any nation until their demands were met.

Pamphlets and newspaper articles attacking slavery were also proliferating in the early 1770s, as many patriots faced the contradiction between their charges that Britain was trying to enslave them, and their enslavement of Blacks. Exemplary are pamphlets or articles written by Benjamin Rush (1773) and Thomas Paine (1775), both published in Philadelphia. But there were many others as well, as abolitionists surfaced in Massachusetts, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Virginia and published their attacks on man-stealing and oppression of the Black race.

This disorganized, but widespread phenomenon spread through almost all the colonies but South Carolina and Georgia from 1776 through the 1780s. Abolition societies were set up (New York, Maryland, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Delaware), anti-slavery legislation was passed (Vermont, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut), and manumission standards were loosened.[8]

The Cause of Freedom

From the above, one thing should be totally clear: a significant number of American revolutionary patriots, including prominent political leaders, considered the abolition of slavery an important part of the demand for freedom from British tyranny. As we commemorate and celebrate the 250th anniversary of our Revolution, let us learn about and include that moral battle, which was unique in the world at that time.

[1] Click here to learn more about the revolutionary changes in 1775.

[2] This thesis is elaborated in Gordon S. Wood’s 2021 book, Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution.

[3] The phrase in quotes comes from the Fairfax Resolves, which can be accessed here.

[4] Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson founded the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in that year. Sharp had received Benezet’s writings and been in correspondence with him since the 1760s.

[5] See Anthony Benezet, “Observations on the Enslaving, Importing and Purchasing of Negroes” (Philadelphia, 1759), reprinted with a fine introduction by Thomas Wolf, in Early American Abolitionists, James G. Basker, General Editor, (New York, 2005), 1-30, quote at 14.

[6] “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” passed in March 1780 in the state of Pennsylvania, reprinted with an expert introduction by Sam Rosenfeld of Columbia University, in Basker, ed., Early American Abolitionists, 89.

[7] Click here for the extensive review of the PAS’s history.

[8] Much more can be found in my book Defeating Slavery: Hamilton’s American System Showed the Way.

Related Posts

Tags: abolition, American Revolution, Anthony Benezet, Nancy Spannaus, Pennsylvania Abolition Society, slavery