Book Review: “Rosalie Gardiner Jones and the Long March for Women’s Rights” (McFarland) By Zachary Michael Jack

Even with my hundreds of clippings of the “Pilgrim’s March” in March of 1913, there are always gaps in our understanding. In the Elisabeth Freeman collection there are precious few personal references that would help us understand how she felt about the events she was caught up in. So, Jack’s book, which draws upon the papers of Rosalie Jones, as well as newspaper archives, fills in many gaps. His well researched and documented book has no fewer than 38 entries in the index about Elisabeth, a veritable feast for this amateur historian.

Jack acknowledges that Rosalie regarded Freeman as a mentor, especially in their Ohio campaign where Elisabeth would chat up the farmers in the countryside, pull into a small town, schedule a gathering for the evening, fit in a street speaking engagement, and of course, touch base with the local newspaper. Jones in that period seemed wide-eyed and shy about public speaking, but by the time of the Pilgrim’s March, her leadership talents emerged.

I have always wondered about choosing the precedent of a “Pilgrim’s” March, invoking the Crusades perhaps, but Elisabeth’s choice of playing the part of a gypsy is puzzling. In the promotion of the trek they claimed that gypsies always accompanied such marches. Was this something that people at the time could reference or were they trying to capture the religious zeal for the cause? According to Jack’s book, there may have been some calculus in the gypsy get up. The situation in England with the militant suffragettes was heating up and placing bombs in Lloyd George’s residence was much in the news. To have Freeman as part of the Pilgrims with her endorsement of those militant strategies might have been controversial. But to have a gypsy tagging along the Pilgrims was seen as sufficient distance from the violence in England. (Previously, I thought that Elisabeth refused to wear the plain brown wool cloaks designed for the hikers and came up with a story that would allow for something more colorful. And, the book mentions that her skirt was red and yellow checks, which is somehow pleasing to know.) p. 37-38

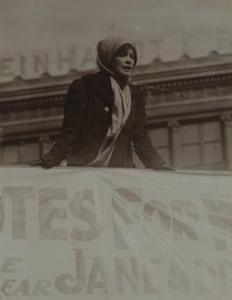

One excellent feature of this book is the detailing of the harshness of female stereotypes and how the band of marchers had to constantly defend their femininity. They had to prove they could darn their socks for instance, and wear fancy dresses and shoes at dances given in their honor after a day’s slog through the mud. Young and pretty marchers were besieged by suitors and what we might call stalkers and rowdy college boys let loose mice to scare the ladies. Elisabeth, being older, missed most of this attention, but brought down scathing criticism when she lit up a cigarette. Much was made of who on the march was a “Miss” and who was a “Mrs.” suggesting that they were not feminine enough for marriage. Elisabeth objected strenuously to the sexist distinction, “I am not Miss Freeman. I am plain Elisabeth Freeman. If I get married I shall be Elisabeth Freeman to the end of the chapter. Why should I have to announce my name by answering such a strictly private matter as to whether I am married or not?” (p. 150)

When the hikers reached Wilmington, Delaware, they had a rare day off and Freeman couldn’t wait to make a day of suffrage campaigning. “(She) woke early, making calls to organize the educational campaigns for a day which would include visits to Wilmington factories and businesses.” Jack writes, “For the first time in the march to date, Freeman had more than one day in which to canvas a city and as she readied herself for a day of soapbox speeches and corner meetings she found herself emphatically in her element.” (p.109)

When the hikers reached Wilmington, Delaware, they had a rare day off and Freeman couldn’t wait to make a day of suffrage campaigning. “(She) woke early, making calls to organize the educational campaigns for a day which would include visits to Wilmington factories and businesses.” Jack writes, “For the first time in the march to date, Freeman had more than one day in which to canvas a city and as she readied herself for a day of soapbox speeches and corner meetings she found herself emphatically in her element.” (p.109)

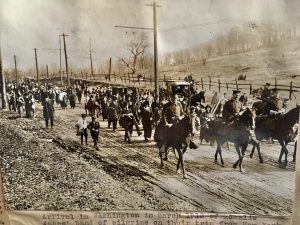

The other detail that is fleshed out thoroughly is the road conditions along the march. Apparently, roads in Maryland were literally mud and state officials were embarrassed into bringing loads of cinders for the roads. One account of marchers being up to their ankles in mud and cars and Elisabeth’s literature wagon being bogged down to the axles bring home just how arduous this march was.

There were some behind the scenes conflicts revealed, not just with “national” and Alice Paul who stole Jones’ thunder, but also within the group. Amid press speculation that Rosalie was near a breakdown it seems that Colonel Ida Craft stepped in, sometimes questioning Jones’ decisions. Nearing Washington Craft split off from the main group to honor a speaking engagement. There was also dissent about whether militancy was a good strategy which a Quaker member of the band objected to. It turns out Elisabeth served as peacemaker between Jones and Craft, which I found surprising because although she could be diplomatic, she was more likely to be controversial. Still, Elisabeth had spent time with both Jones and Craft and respected their work so perhaps it pained her to have friends fight.

Freeman and Jones took different paths after the march, with Jones staying with NAWSA, the more conservative state by state organization, and Freeman “eagerly” joining Alice Paul’s Woman’s Party which picketed the White House and went to jail for the Cause. There is no indication of rancor, but they led different lives—the millionaire’s daughter and the working woman activist.

Zachary Jack has taken a slice of history and done a deep dive, one which highlights the larger movement and fills in lots of gaps. Good work!!