In his 2003 paper, Are We Living in a Computer Simulation?, philosopher Nick Bostrom suggested the possibility that, in the future, civilisations might be so technically advanced that they might fancy running “ancestor simulations” of the sentient beings in their distant past. Following that hypothesis, our bodies, our minds and the physical world that we currently inhabit could very well be little more than a computer simulation engineered by those future beings.

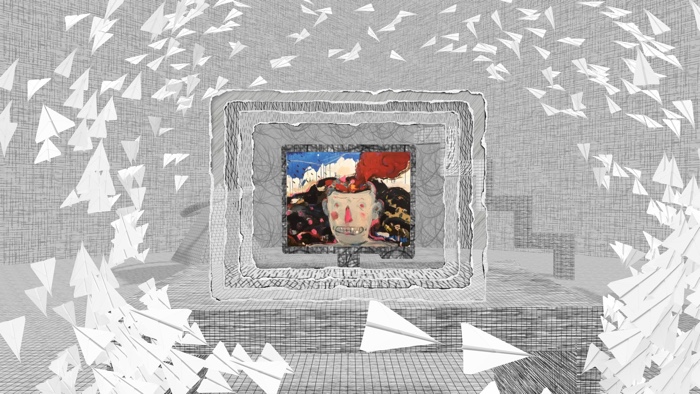

Piotr Winiewicz, About a Hero, 2024

Ruben Cabenda, Töngö sondi, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

This year’s edition of IDFA DocLab, the platform for interactive and immersive documentary art at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, has chosen as its theme This Is Not a Simulation. The title celebrates the twofold power of technology. On the one hand, VR, AR, AI and other technologies can produce virtual life-like creatures, immaterial wealth and absorbing software constructs. On the other hand, those same technologies can bring about physical experiences and authentic feelings. And none of those experiences are simulated.

Aphra Taghizadeh, Speechless Witness of a Wandering Tree / شاهد گنگ درخت سرگردان, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

IDFA DocLab‘s selection of works also plays with the Janus character of technology: to make us escape from reality and ground us firmly into it. One work connects rice with transatlantic slavery. Another explores how, in recent years, rulers of countries such as Iran, Bangladesh and Chile have deliberately blinded their citizens. One installation suggests what a safe space for queer people might feel like. Another imagines how autonomous technological entities will one day merge with plants and fungi.

Since 2007, DocLab’s ambition has been to investigate how artists are using new technologies to tell compelling stories. This year, many of the works selected are using AI to convey these stories. However, no matter how impressive the algorithms are, they never prevail over the human. You can always identify the critical, subjective, playful and deeply human handiwork in the immersive art pieces, AI experiences and live performances shown in the programme. So no, this is not a simulation, people. At least not yet.

Here’s a (far too small) selection of the works I particularly enjoyed in the IDFA DocLab exhibition:

Tamara Shogaolu, Oryza: Healing Ground, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Tamara Shogaolu, Oryza: Healing Ground, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Tamara Shogaolu, Oryza: Healing Ground, 2024

Tamara Shogaolu, Oryza: Healing Ground, 2024

Only two rice species have been domesticated throughout human history. The most widely known is Oryza sativa, domesticated in China approximately 10,000 years ago. The other, Oryza glaberrima, is less famous and was not recognised as a unique species until the mid-20th century. Its history is grounded in the inland delta of West Africa’s Niger River, where it was domesticated some 3,500 years ago.

Oryza: Healing Ground, an AR installation by Tamara Shogaolu, explores the entanglements between Oryza glaberrima and transatlantic slavery.

African rice was brought to the Americas with the slave trade. The seed was carried as provisions on slave ships. However, African women, who had always played a major role in rice cultivation, braided rice and other grains into their hair as a kind of counter-plantation stratagem. Cultivating African rice according to their own traditions allowed enslaved people to claim a space of autonomy, enrich their meals and remain connected to their roots. The high price of rice on the market made rice-growing skills profitable and newly imported enslaved Africans were “advertised” for the specialised farming skills and techniques needed to grow the grain and advance its diffusion.

Oryza: Healing Ground tells the forgotten story of the first Black farmers of the USA. The work combines art, archives, AI and interviews with Natalie Baszile, Akua Page and other champions of the Black land movement that resist the US Department of Agriculture’s quiet sabotage of African American farmers.

By using AI to enliven archival material, the artist not only generated new images that are based on her own biases, but she also weaved a counter-history narrative that addresses the exclusion of marginalised perspectives from traditional archives and AI-generated imagery. I would like to see more works like Oryza, more works that show both finesse and combative spirit.

Zhuzmo, All I Know About Teacher Li, 2024

Zhuzmo, All I Know About Teacher Li, 2024

Teacher Li is an anonymous Chinese artist living in Italy. He had the habit of sharing on Weibo (a kind of Chinese version of Twitter) all kinds of videos and news stories that the Chinese government would have preferred to keep quiet. Each time he published an undesirable story, Weibo censored it and swiftly kicked him off the platform. He kept registering under different names until Weibo banned him completely. So he moved to Twitter.

During the COVID pandemic, Teacher Li’s account became the go-to newsroom for all stories related to zero covid policy: from zealous restriction enforcers to people so desperate they threw themselves from rooftops, from acts of resistance to humorous videos explaining how to hoist your dog from the window so that it can have a walk in the street while you are locked inside a flat. Each time, a Chinese citizen found something worth sharing, they sent it to Teacher Li who would then publish it on Twitter. Thanks to him, millions of Chinese citizens realised that the frustration with the drastic containment measures was growing fast. One day, Teacher Li received a video showing a woman standing in front of a university and holding a blank sheet of paper. The white space of the A4 stood for everything Chinese citizens would say if censorship weren’t so rampant. Over the following days, other videos like that one emerged. Only with more and more people and in various cities across the country. At the height of the White Paper protests, more than a million people in China were following Teacher Li.

Zhuzmo’s interactive VR film All I Know About Teacher Li tells the story of Teacher Li, of the absurd Covid restrictions and of the collective (and eventually successful) efforts to convince the government to allow the return to normal life.

Zhumo (again, not a real name, as it is safer for the artist to remain anonymous) did a great job with this 20-minute VR documentary. The interactive element is pretty unspectacular (you have to grab and throw paper planes to launch the next video) but everything else is brilliant: the hand-drawn animation, the citizen footage converted into 3D, the storytelling that shows the power of solidarity, perseverance and social media activism. All I Know About Teacher Li is a very moving piece. Special thanks to the VR headset that hid the tears in my eyes.

mots (Daniela Nedovescu and Octavian Mot), AI & Me, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

mots (Daniela Nedovescu and Octavian Mot), AI & Me, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

mots (Daniela Nedovescu and Octavian Mot), AI & Me, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

AI & Me invites you to see yourself through the “eyes” of AI. You sit for a moment on a chair in front of a screen and wait for the machine to judge you. If you are looking for validation, reassurance and flattery, you might be disappointed. The algorithm wasn’t made to please. I was happy to be identified as a “young Asian male who loves vintage fashion.” Others found the conclusions of the machine a bit raw and grating. Most found it hilarious, though. After its assessment, the system displays a series of modified photos of you on nearby screens.

As is often the case with AI, we have no clue about the dataset the machine was trained on. It remains a black box. Through its interpretation and conclusion about people, however, we might be able to guess the biases embedded in the system and the societal structures that shape them.

The irony of the work is that at a time when we read again and again that privacy is crucial and we should be more suspicious of AI systems, we find it hard to resist a machine that judges us. We just love mirrors, even deforming ones. Maybe the work should be called Me & AI.

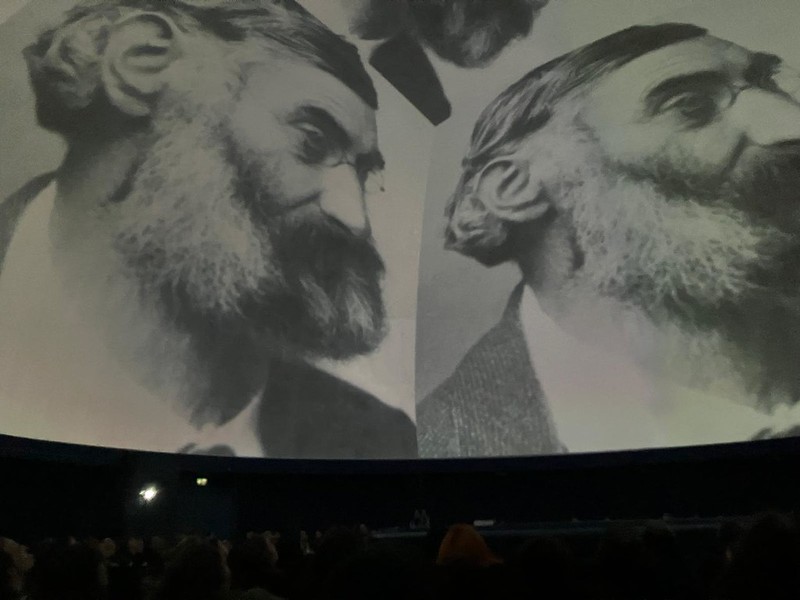

Felix Heyes and Ben Wes, Google volume 2, 2024

Felix Heyes and Ben Wes, Google volume 2, 2024. Google 2 Dome IDFA Doclab

Felix Heyes and Ben Wes, Google volume 2, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

10 years ago, Felix Heyes and Ben West published Google, volume 1, a paper dictionary where the 21,110 words and definitions have been replaced by the first image that appeared on Google Images for that word. The physical version of Google image archive was given a revamp this year. The exercise was exactly the same. The images often changed (but not always), sometimes the photo was replaced by a commercial logo, sometimes it was the design that changed, sometimes the meaning assigned to a word differed. What is striking, however, is how aesthetically poor many of the images are: lousy graphics, stock images, generic photos.

Alaa Al Minawi, The Liminal, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Alaa Al Minawi, The Liminal, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab. Photo: Nina Schollaardt

The Liminal is a wall. In all its beige blandness. As you go closer, you can hear the people living inside the wall. They talk about the roles of a wall (separating, protecting or both), about how they deal with boundaries and oppressive systems.

Alaa Al Minawi‘s work imagines a world where all borders and all no man’s land combine into one single state. Unsatisfied with the injustices and quarrels of the world, its inhabitants have quietly retreated within its boundaries. This invisible community moves inside the wall and you have to glue your ear to the surface and move along the white surface to follow their stories. You’re an outsider. You can’t join them but you can listen and reflect on division, unity and privileges.

Seán Hannan, You Can Sing Me on My Way, 2024

Seán Hannan (i.c.w. B-Lab (Bram van Es)), You Can Sing Me on My Way, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

You Can Sing Me on My Way -which design is inspired by René Magritte’s painting La voix des airs– plays sean-nós songs. This Irish Gaelic style of singing is dating back to a time when the written word did not exist. One of their roles was to pass on the memory of important events. The tradition is now dying out.

Seán Hannan used a specially trained AI to revitalise sean-nós. New lyrics are created based on the contemporary news stories that the algorithm considers important, songs are generated and added to a database. This produces the new lyrics, compositions and vocals that are heard continuously from this installation.

Visitors can read an English translation of the Irish Gaelic lyrics on their phones.

More works and images from DocLab exhibition:

Emeline Courcier, Burn from Absence, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

DocLab VR Gallery. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Queer.Space, DOLLHOUSE for Queer Imaginaries, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Pegah Tabassinejad, Entropic Fields of Displacement. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Sister Sylvester, Drinking Brecht: An Automated Laboratory Performance, 2024. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Marcel van Brakel and Hazal Ertürkan, Future Botanica. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Marcel van Brakel and Hazal Ertürkan, Future Botanica. Installation view, Idfa Doclab

Idfa Doclab at de Brakke Grond

The IDFA DocLab exhibition is closed. If you want to hear more about the 18th edition of IDFA DocLab, check out Voices of VR‘s interview with curators Caspar Sonnen, Nina van Doren and Toby Coffey: IDFA DocLab Curators Preview 2024 Slate of AI & XR Immersive Documentaries.