Article begins

In a country full of negative perceptions about China, Jehovah’s Witnesses persist in reaching out to Chinese communities—by learning to conduct church services in Chinese.

Under the 1996 constitution, Zambia officially became a “Christian nation,” with 95.5 percent of the population being Christian. The Jehovah’s Witnesses have enjoyed remarkable evangelical success in Zambia, and more than 3,000 Jehovah’s Witness congregations have been established in the country since 1911.

Like Jehovah’s Witness congregations in the rest of the world, Kombela Central Mandarin Congregation is governed by local elders in charge of pastoral work, selecting speakers, and directing public preaching. Congregants meet twice a week to read and discuss the Bible, have Q&A sessions for The Watchtower magazine teachings, and sing worship songs. But even though nearly all the congregants are Zambian, what makes the meetings in the congregation special is that they are all conducted in Mandarin.

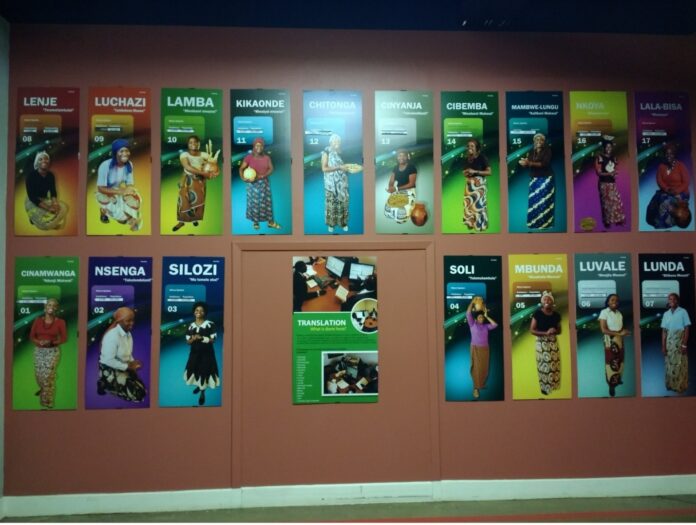

A poster board advertising the many Zambian languages that Jehovah’s Witnesses preach in.

Credit:

Justin Lee Haruyama

A poster board advertising the many Zambian languages that Jehovah’s Witnesses preach in. In addition to these Zambian languages, there are also “foreign-language” congregations which preach in Mandarin, Gujarati, French, and sign language. Lusaka, Lusaka Province, Zambia. May 2018.

Jehovah’s Witnesses are a highly centralized organization. The headquarters in New York decides every meeting agenda of congregations worldwide. They also decide the congregation’s language, considering the population of potential preaching targets. Besides congregations that conduct their meetings in various Zambian languages, there are Mandarin-, Gujarati-, and French-language congregations in Zambia. The fast-growing Chinese immigration in Zambia is why Mandarin was chosen as this congregation’s language, so that members could more easily evangelize.

A crew at a Chinese-operated coal mine prepare to descend underground, overseen by their Chinese shift boss.

Credit:

Justin Lee Haruyama

A crew at a Chinese-operated coal mine prepare to descend underground, overseen by their Chinese shift boss. Summers Coal Mine, Southern Province, Zambia. September 2015. © A crew at a Chinese-operated coal mine prepare to descend underground, overseen by their Chinese shift boss. Summers Coal Mine, Southern Province, Zambia. September 2015.

In a one-on-one Bible study group, Justin Haruyama was paired with Jonah. Jonah grew up in a Witness family in Kitwe, the largest city in the Copperbelt area and a center for Zambia’s growing Chinese migrant community. Jonah and his family learned Mandarin with a Mandarin-language congregation in Kitwe so they could preach to local Chinese migrants. When Justin met Jonah, Jonah was in his mid-20s, speaking fluent Mandarin after eight years of training from the congregation in his hometown.

A few years ago, Jonah moved to Kombela, a city in south-central Zambia, to reach more Chinese migrants, whom he worried “would not be receiving the truth of the Bible.” Jonah spent a minimum of 70 hours per month evangelizing to the Chinese community. Like all other members of his congregation, Jonah kept meticulous track of the hours he spent following Jesus’ command that disciples spread the Truth of biblical teachings to all nations.

But for some like Jonah, learning Chinese could also provide them with employment opportunities. The proliferating Chinese companies and factories seek locals who are proficient in Chinese. Jonah had worked in the past as a part-time IT consultant for various Chinese businesses around Kombela. However, Jonah quit this job because he was asked to assist with some tasks he felt were “unethical,” such as helping the company lie on official government forms or providing bribes to Zambian government officials. He said that he was not interested in using his Mandarin proficiency in the secular world if it meant compromising his religious principles, even if it offered the promise of earning a great deal of money. When he realized there was a conflict in applying his Mandarin proficiency between secular and religious work, he abandoned the secular in favor of the spiritual.

A sign with Chinese letters in front of a building.

Credit:

Justin Lee Haruyama

The entrance to a “Chinese Market.” Central Zambia. November 2018.

Jonah’s prioritization of his religious values over what he called “secular work” is not unusual for Witnesses in Zambia. Other Witnesses in Jonah’s congregation found ways to manage their finances so that they could retire early, downsize their homes and standard of living, and devote themselves full time to evangelizing. In a context of Zambian Christianity where otherwise the Prosperity Gospel is extremely strong and in which many non-Witness Zambians see Christian faith as a route to material advancement, the material downsizing that many Zambian Witnesses pursue sets them apart. Perhaps one factor in these Witness practices, and their willingness to learn Mandarin and befriend Chinese migrants, is the deep Witness theological engagement with eschatology and precise calculations of the coming end of the (secular) world.

Among other things, Witness eschatological theology leads them to view all human governments as necessarily under the power of Satan—despite the claims of the Zambian government enshrined in the Zambian constitution, for example, that Zambia is a “Christian nation.” Awaiting a coming theocratic government ruled directly by Jehovah and Jesus that would recognize no prior distinctions of race or nationality, Witnesses are relatively indifferent to worries expressed by other Zambians that China is “buying up” Zambia or that Chinese migrants might exert a corrupting influence on the Zambian government. Although there are widespread negative perceptions toward proliferating Chinese communities in Zambia, Witnesses regard this nationalist or racially tinged xenophobia as irrelevant to fulfilling their mission.

Even with increased interactions through evangelizing, there have been growing anti-Chinese sentiments in Zambia in recent years, often based in economic inequalities between the countries. According to the China Africa Research Initiative at John Hopkins University, Zambia owed Chinese creditors US$ 6.6 billion as of August 2021, and accusations of China’s “debt-trap diplomacy” have been frequently repeated in Zambia, especially during the campaign in August 2021. Added to this is the perilous working environment of Zambian workers in Chinese companies. In 2020, amid heightened tensions between Zambian and Chinese migrant communities, with the mayor of Lusaka Miles Sampa accusing Chinese migrants of practicing “slavery reloaded,” a small group of Zambian assailants murdered, dismembered, and burned the bodies of three Chinese operators of a textile warehouse.

A muddy old coal mine

Credit:

Justin Lee Haruyama

The landscape just outside one of the mining shafts of a Chinese-operated coal mine. Summers Coal Mine, Southern Province, Zambia. September 2016.

In contrast, Jehovah’s Witnesses make every endeavor to preach to as many Chinese people as possible by learning their language. This striking contrast in judging the Chinese migrant communities reflects how Jehovah’s Witnesses are relatively uninterested in the negative portrayals of Chinese people in Zambia. For them, the barriers to converting Chinese expatriates are cultural instead of ontological: not a matter of different kinds of souls, as described by some other Zambian Christians, but rather of linguistic misunderstanding. For Witnesses, the establishment of God’s kingdom over the Earth is the only solution for all problems faced by humanity, and spreading this truth to Chinese migrants as quickly as possible is of paramount importance.

However, it is not always easy for Jehovah’s Witnesses to approach Chinese communities. Some Witnesses approach Chinese shoppers in shopping malls. Chinese shoppers described to Justin being surprised and impressed by Witnesses’ Mandarin proficiency, though they sometimes became less enamored of the conversation when they realized it was directed toward evangelization. For those Witnesses who did door-to-door preaching, they were occasionally met with hostility in Chinese households. For example, most Chinese migrants in Zambia live in walled compounds, and some Chinese migrants released their guard dogs to chase Witnesses back to the entrance gates.

China has the world’s largest irreligious population, and the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is officially atheist. As a result, few Chinese migrants arrive in Zambia with much experience of overt religiosity, especially not with religions such as Christianity. Nevertheless, being alone in a foreign country prompts a few Chinese to open up to Jehovah’s Witnesses’ enthusiasm. Mr. Cheng, a bible study student who managed a construction company in Zambia, was one among those who had a favorable impression toward the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Kombela Central Mandarin Congregation members regularly went to Mr. Cheng’s house to teach him about the Bible. Mr. Cheng was deeply impressed by the congregants’ moral character, as he told Justin how he had never seen them lose their temper on any occasion. Such a manner encouraged Mr. Cheng to dive into Witness teachings. Mr. Cheng described having problems with anger in the past, and he felt that Witness teachings could help him rectify this.

The cordiality of the members in Kombela Central Mandarin Congregation to Chinese communities and their commitment to accepting Chinese culture are relatively unusual qualities in Zambia, where otherwise xenophobia toward Chinese migrants is more common. This greatly impressed Mr. Cheng. As mentioned, their open attitude towards Chinese migrants paralleled their relative indifference to contemporary political events, which made them less likely to accept negative stereotypes about foreign communities. Witnesses’ adherence to the Bible transcends the kinds of histories in secular society that emphasize a world order dominated by competition between nation states. Witnesses instead work to spread what they refer to as “the truth” to all humans. Categorizing humans by country or by race is therefore usually far less salient for Zambian Witnesses than it is for other Zambian Christian communities.

The emerging trend of Mandarin-language Jehovah’s Witness congregations in Zambia reveals the religious dimension of the relationships between China and Africa. In this dimension, the interactions are not as straightforward as mere economic or political engagements. Religious, spiritual, and eschatological concerns also shape the possibilities of integrating the new Chinese communities and Africans. Using a religious dimension to see how Chinese and Africans are interacting today is a useful tonic, since it belies more usual economic and financial premises that frame African nations and societies as passive partners in an unequal exchange.

The names of people and places in this article have been anonymized in order to protect the identity of Haruyama’s research participants.

Jean Hunleth and Samar Al-Bulushi are the section contributing editors for the Association for Africanist Anthropology.