THIS is what transformed humanity between 300,000 and 100,000 years ago – the development of a cultural system of environmental management that made the ecosystems of the world into gardens. And we of the “civilized” states, today, mistakenly call this all a “natural wilderness”. This brings forcibly to mind what Ragai, a Kua hunter I knew in the Kalahari, told me one day when I asked why the antelope and other game was unperturbed when they saw us walking past them:

“Only frightened animals are wild”, he explained, “to us, they are tame”.

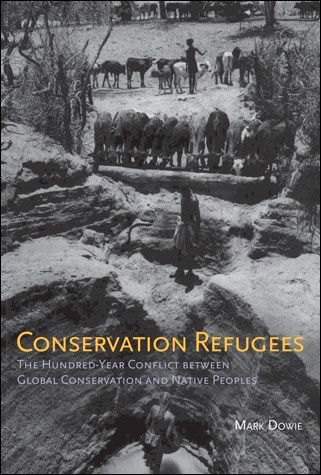

Below are some excerpts from an article by Mark Dowie, that appeared the MIT Press Reader.

“…In the course of “preserving the commons for all of the people,” a frequently stated mission of national parks and protected areas, one class or culture of people, one philosophy of nature, one worldview, and one creation myth has almost always been preferred over all others. These favored ideas and impressions are at some point expressed in art. And it is through art that our earliest preconceptions and fantasies about nature are formed…”

“…When I tried to explain what I meant by wild to Bertha Petiquan, an Ojibway woman in northern Canada whose daughter was interpreting, she burst out laughing and said the only place she had ever seen what she thought I was describing as wild was a street corner outside the bus station in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

In Alaska, Patricia Cochran, a Yupik native scientist, told me “we have no word for ‘wilderness.’ What you call ‘wilderness’ we call our back yard. To us, none of Alaska is wilderness as defined by the 1964 Wilderness Act — a place without people. We are deeply insulted by that concept, as we are by the whole idea of ‘wilderness designation’ that too often excludes native Alaskans from ancestral lands.” Yupiks also have no word for biodiversity. Its closest approximation means food. And the O’odham (Pima) word for wilderness is etymologically related to their terms for health, wholeness, and liveliness.

Jakob Malas, a Khomani hunter from a section of the Kalahari that is now Gemsbok National Park, shares Cochran’s perspective on wilderness. “The Kalahari is like a big farmyard,” he says, “It is not wilderness to us. We know every plant animal and insect, and know how to use them. No other people could ever know and love this farm like us.”

“I never thought of the Stein Valley as a wilderness,” remarks Ruby Dunstan, a Nl’aka’pamux from Alberta. “My Dad used to say ‘That’s our pantry.’ Then some environmentalists declared it a wilderness and said no one was allowed inside because it was so fragile. So they put a fence around it, or maybe around themselves.”

The Tarahumara of Mexico also have no word or concept meaning wilderness. Land is granted the same love and affection as family. Ethnoecologist Enrique Salmon, himself a Tarahumara, calls it “kincentric ecology.” “We are immersed in an environment where we are at equal standing with the rest of the world,” he says. “They are all kindred relations — the trees and rocks and bugs and everything is in equal standing with the rest.”…