When documentary editors begin a project, we expect it to cover certain topics. I was confident, when I started preparing Zachary Taylor’s and Millard Fillmore’s letters for publication, that the letters would cover topics I associated with America in the 1840s and 1850s. They would discuss the Mexican-American War, the expansion of slavery, the cholera pandemic, tariff reform, immigration from Germany and Ireland, and the forced removal of Indigenous peoples. On a more personal level, they would discuss Taylor’s and Fillmore’s families, the day-to-day lives of those Taylor and others enslaved, and specific political and diplomatic relationships.

Other topics come as surprises. Presidents wrote and received thousands of letters. We’ve already located nearly five thousand from the decade ending with Fillmore’s administration. Those embrace a wide variety of correspondents and interests, both within and outside the anticipated. I knew the war would show up, but I didn’t know that Taylor corresponded with engineers about setting up a line of flags to communicate across Mexico by semaphore (the letters appeared in the Baltimore Commercial Journal, and Lyford’s Price-Current, November 6, 1847). I might have expected letters about art, but I didn’t know that Fillmore corresponded with Elizabeth Milligan about her miniature painting of the former first lady Dolley Payne Todd Madison (Milligan’s letter of June 5, 1844, is in SUNY–Oswego’s Millard Fillmore Papers).

I also did not expect to find much about Haiti. Perhaps I should have known better. Through a violent revolution that lasted from 1791 to 1804, Haiti’s enslaved Blacks overthrew the French colonial government. They set up an independent government and excluded Whites from citizenship. Haitians’ success prompted fears among US Whites that the people they enslaved would launch similar uprisings. Those fears, which persisted for decades, helped motivate state laws restricting US Blacks’ freedom and literacy. (You can read more about Haiti in this era in books by Steeve Coupeau, Philippe Girard, and Robert Debs Heinl et al.) So I might have expected to read about Haiti in letters of the 1840s and 1850s, or at least about US perceptions of it.

Personal relationships, though, are key. Both Taylor and Fillmore, it turns out, had close ties with White Americans who spent time in Haiti. Taylor’s second cousin William Taylor, whom he often mentioned in letters, served as agent or consul at Port-au-Prince and Cape Haytien in the 1810s. More important for our period, Millard and Abigail Powers Fillmore were close friends with the Manhattan couple Joseph C. and Julia A. Mason Luther. Millard corresponded with both. Joseph, as it happened, served as US commercial agent at Port-au-Prince from 1843 to 1849.

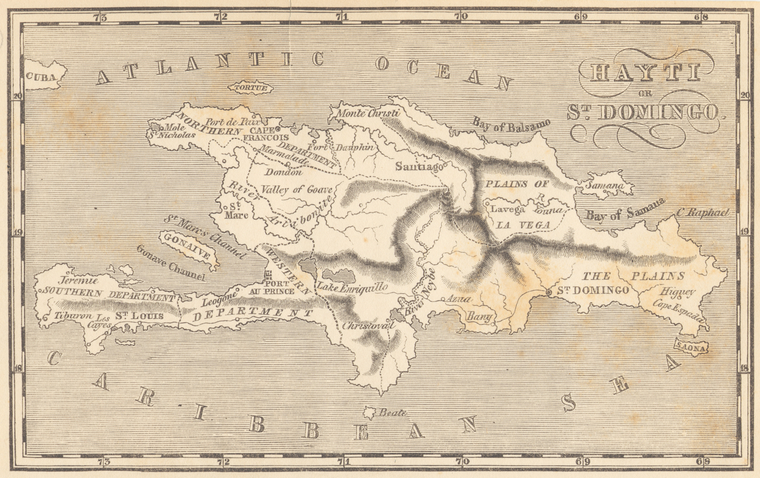

Map by J. R. Beard of Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1853. New York Public Library.

Joseph Luther wrote Fillmore detailed letters about politics and culture in Haiti. He was there during a tumultuous period. A series of new revolutions rocked the country beginning the year he arrived, as did a major earthquake and fire. Luther recounted the formation of a new constitution and the succession of political and military figures who tried to establish control.

Luther didn’t want to be there. He shared the day’s racist assumptions about People of Color and low esteem for a Black-ruled nation. He told Fillmore on February 21, 1844, that he would rather “have obtained an appointment to some prominent port in Europe, or even in South America, but their being no vacancy of that discription, . . . I was compelled to accept of such as there were, or get none at all.” With Julia back in the United States, furthermore, “I am . . . most wretchedly lonesome out here amongst the negroes.”

Luther’s criticisms of Haitians ranged from the political to the cultural. He described the constitutional convention, in the same letter, “as somewhat of a sumary way of forming Governments” by US standards, “but it goes down here as perfectly orthodox.” He conceded that lighter-skinned Haitians included “many well educated and talented men” but insisted that “the commonality of the people, are quite uneducated, and exist in the lowest state of moral degradation that it is easy to conceive.” He described Carnival, Haiti’s February celebration, as embracing “caps and cocked hats of gaudy appearance” and “instruments for making noises of the strangest and most heathenish sounds possible.”

A week after Luther wrote that letter, another revolution arrived. Since 1822, Haiti had comprised the entirely of the island of Hispaniola. Now eastern residents declared themselves the independent Dominican Republic. War ensued, but Luther reported on June 10 that the Dominicans had prevailed. In what remained of Haiti, he predicted “that the whole government will become dismembered, and formed into small districts or tribes, similar to those of the Indians on our Western Frontiers.” On September 15, 1845, he added that the government remained “in a deplorable condition” and observed that, with most men recruited as soldiers, “nearly all the produce which has come to market . . . have been the fruits of female labour.”

Joseph Luther still wasn’t happy about his assignment. Neither was Julia. She asked Fillmore on November 4, 1846, to use his influence to get Joseph a job in New York, “so he may hereafter be at home.” If Fillmore tried, he failed. But the Luthers’ discontent redounds to history students’ benefit. Joseph continued writing to his friend from Haiti until 1849. The transcribed and annotated letters, published in our digital and print volumes, will become new sources both for events in that country and for US attitudes toward it. The Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore will shed light on both expected and surprising facets of life in the mid-nineteenth century.

Speaking of those volumes, I have an update on our progress. Longtime readers of this blog may recall my forecast that we editors would send our first volume to the publisher this winter. Research, though, sometimes yields an overabundance of riches. We’ve found even more letters and even more sources to annotate them than we’d expected. So we’ve planned some extra research trips to make the volume as complete and informative as possible. I was at the National Archives just this month. We’ll be completing volume 1, which will cover January 1844 to June 1848—and include all the Luthers’ letters quoted here—in the spring. You can expect to see it online and on bookshelves in the spring or summer of 2026. It will be an exciting new source for US history as the nation celebrates its 250th birthday.

Manuscript records at the National Archives in Washington, DC.