By Nancy Spannaus

Feb. 3, 2025—On February 1, my husband and I had the pleasure of attending a celebration of National Freedom Day in Northern Virginia. We joined a small number of fellow citizens, Black and white, at a ceremony, which began with the ringing of church bells 13 times, commemorating President Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on February 1, 1865.

The event, sponsored by the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation and the National Freedom Day Association, was also livestreamed to various locations around the United States and internationally.

But what, you may ask, is National Freedom Day? Despite being amateur historians devoted to American history and civil rights, my husband and I had never heard of it before this event. Most likely, you haven’t either. As I review the program below, you will learn what we discovered about this day of National Observance and its significance.

The Establishment

February 1 was declared National Freedom Day by President Harry S Truman on January 25, 1949. The Proclamation followed the passage of the joint resolution by Congress in June of 1948, which authorized the President to “proclaim the first day of February of each year as National Freedom Day in commemoration of the signing of the resolution of February 1, 1865.” Truman’s declaration so designated the annual February 1st observance, and called “upon the people of the United States to pause on that day in solemn contemplation of the glorious blessings of freedom which we humbly and thankfully enjoy.”

The driving force behind this act of recognition was Major Richard Robert Wright, Sr., a former slave who became a prominent educator, businessman, and public servant. His history, summarized here, is an impressive story of achievement and public service. Wright began his campaign to recognize the significance of February 1st in 1941. He established the National Freedom Day Association, whose purpose is “to keep alive and insure that the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments of the United States Constitution are not forgotten by the younger generation.” Celebrations began in Philadelphia that year, emphasizing the commitment of the nation to freedom for all.

Major Wright’s efforts to establish the day of observance finally met success a year after his death.

The Ceremony Begins

After the ringing of the bell at the Sterling United Methodist Church, which hosted this year’s event, the Reverend Mark Winborne opened the event with the traditional Call to Order.

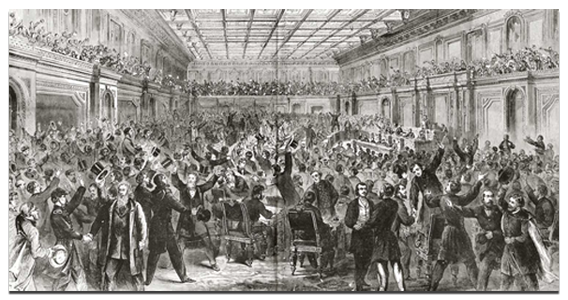

“Hear ye, hear ye. On this day in 1865, President Lincoln signed the 13th amendment ending slavery in the United States. The night before, on January 31, 1865, the United States House of Representatives passed the bill sent to them from the United States Senate on April 8, 1864.”

This was followed by the reading of the 13th Amendment, which goes as follows:

Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Dr. John H. Jones III, president of Juneteenth Loudoun, followed up by describing Major Wright’s effort to establish the Feb. 1 Day of Observance, as I summarized above.

Reflections on the 13th Amendment

Steve Williams, president of the National Juneteenth Observance Association, then provided reflections on the “wave of freedom” which began with the passage of the 13th Amendment, and reached higher crests over ensuing months. People get discouraged today, he said, but those days were even more tumultuous, and far worse in many respects. Yet out of that upheaval came great progress, he said.

The 13th Amendment was not an innovation, Williams explained. It took its language from the Northwest Ordinance which banned slavery except in the case of punishment for a crime.[1] He noted as well that the Amendment makes no reference to ethnicity.

The Amendment’s signing was a hallmark in the civil rights movement: Martin Luther King would ring a bell on Feb. 1st; the 1960s sit-ins began on that day. It truly began a “wave of freedom.”

But this wave should not merely be applied to African Americans. I don’t like this labelling of Americans by ethnicity, Williams said. We are all Americans and should be brought together on that basis.

A Youth Perspective

After a prayer, the audience was treated to a presentation by James Wyllie, a senior at a local high school, who had prepared his talk as part of a competition being run by the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation. His speech was entitled “What the Future of the Thirteenth Amendment Means to Me.”

Wyllie took aim at what he called the “loophole” in the Thirteenth Amendment, the clause allowing slavery as punishment for a crime. This clause is being used today to subject many prisoners, many of them African American, to de facto slavery. Using the case of Alabama, he described how trust-worthy prisoners are given special perks on the condition they participate in work programs for such companies as McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s! Versions of such work programs are legal in all but eight states!

As Wyllie put it: this is “today’s prison-industrial complex, where Black Americans are more likely to be arrested, given longer sentences, and disproportionately represented in our prison populations. The only difference between then and now is that the black-and-white striped jumpsuit has been replaced by a red polo with those golden arches on it.”

So, when I think of the future of the 13th Amendment, Wyllie said, I am fearful. President Trump has indicated he would be expanding imprisonment. But “fear should drive us to action.” We youth must act to stop these prison atrocities, end the privatization of prisons, and create an immigration system which treats people with dignity. He concluded with this moving statement:

The 13th Amendment was meant to end slavery. It is up to us to make sure it actually does.

The future of this amendment is not yet written. The pen has not yet been fully lifted.

It is in our hands to ensure a future of true freedom for all.

The Evolution of Black History

Wyllie’s presentation was followed by a short talk by Henri Polgar, executive director of the Panamerican-Panafrican Association, which serves as an NGO at the United Nations. Polgar described the work of his late mentor, Dr. Robert Starling Pritchard, who built on the work of other freedom fighters to create Black History Month 60 years ago today.

Dr. Pritchard, a celebrated African American classical pianist, was dedicated to creating an “inclusive” observance of the contributions of Black culture to American society, Polgar said. He saw American society as a “mosaic,” not a melting pot.[2]

Polgar recounted several key steps toward advancing the recognition of African Americans’ role in building the nation. First was the participation of civil rights giant Frederick Douglass at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Accredited to the Fair as a representative of Haiti, Douglass attracted thousands during the appointed “Colored Persons’ Day,” where he gave a stirring speech on the contributions of Haiti to the United States and joined with his nephew Joseph Douglass in a classical violin performance.

The second step was taken by the eminent historian Carter Woodson, who established the Association for the Study of African American Life and History in 1915, and created “Black History Week” in 1926.

The third contribution was made by Pritchard, who in 1965 – 60 years ago to the day – launched the celebration of Black History Month. A huge gala was held in New York City and New Jersey, and attended by celebrities such as Langston Hughes, Ossie Davis, and others. Pritchard’s initiative was ultimately made into law in 1976 by President Gerald Ford, leading to Black History Month being celebrated today.

In conclusion, Polgar’s wife Lisa read a poem by Pritchard, written for the occasion of National Freedom Day. Entitled “Prayer for the Innominate Slave,” it goes as follows:

May this National Day of Remembrance and Mourning

and the Monument to the Innominate Slave

serve as fitting Memorials,

… to all those of our African forefathers and foremothers

who lie restless,

buried beneath the high seas of the Middle Passage,

with only the crests of its waves as their tombstones…

… to the African victims of the slave-trade holocaust,

yet unavenged by God and man,

who lie restless beneath the soil of this state,

this community,

throughout the states of our country

the Americas and Europe,

in graves marked only by the unredeemed agony of their toil

and the sanctified dust of their bones…

… to those of our ancestral kith and kin

who never tasted freedom in their lifetimes

and who still await the day

when

Through some appropriately humble act of national contrition

they may at long last Rest in Peace.

May our Observance

of this National Day of Remembrance and Mourning

redeem our nation’s sins of commission and omission

against our enslaved African forefathers and foremothers

and their progeny through the centuries.

Call to Action

Gladys Burke, one of the lead organizers of the event, concluded the ceremony by reiterating the “Call to Action” enunciated in President Truman’s 1948 Declaration:

Now, Therefore, I, Harry S. Truman, President of the United States of America, do hereby designate February 1, 1949, and each succeeding February 1, as national Freedom Day; and I call upon the people of the United States to pause on that day in solemn contemplation of the glorious blessings of freedom which we humbly and thankfully enjoy.

After Rev. Winborne’s closing prayer, the celebration ended, with the participants fully committed to expanding participation in the years to come.

[1] The event program also noted that enslavement for a crime had deeper historical roots, going back to Biblical times.

[2] For more on Dr. Pritchard, click here.

Related Posts

Tags: 13th Amendment, Gladys Burke, James Wyllie, John H. Jones, Juneteenth, Mark Winborne, Nancy Spannaus, National Freedom Day, Steve Williams