Herbert O. Yardley was being followed. He knew it, as much as he knew something was off when a beautiful woman struck up a conversation with him at an illegal speakeasy in New York City in 1929. “Her friendliness was a bit forced,” he later recalled. “It did not seem reasonable for one of her beauty and charm to possess such warmth for a bald-headed man.” The drinks flowed liberally as Yardley sipped straight whiskey, only to let it run slowly through his lips into the ginger ale cup used as his chaser. The woman removed a compact mirror from her purse and disappeared into the ladies’ room. Yardley wasted no time in searching the purse but found nothing except $15, a key and two or three handkerchiefs.

At the end of the night, after Yardley helped the stranger home in a taxi, he waited until she fell asleep, then searched her apartment. In a dresser drawer, he found a typewritten note: “Have tried to reach you all day by telephone. See mutual friend at first opportunity. Important you get us information at once.” The cryptologist covered the woman with a blanket and quietly let himself out. Once again, he’d avoided falling into a spy’s trap. Even so, his days as the head of the top-secret Black Chamber agency were numbered.

Long before the creation of the National Security Agency in 1952, the United States opened a top-secret Cipher Bureau known in government circles as the Black Chamber. Founded in 1919, the covert organization spied on American citizens and foreign nations alike. Its employees held no civil service status and were paid in cash from secret payroll accounts. Officially, the Black Chamber didn’t exist until 1931, when its founder, Yardley—bitter after an abrupt dismissal—decided to expose it to the world in a tell-all book titled The American Black Chamber. Eighty-two years before the infamous 2013 security leak by government contractor Edward Snowden, the U.S. was on the precipice of one of its first major intelligence scandals.

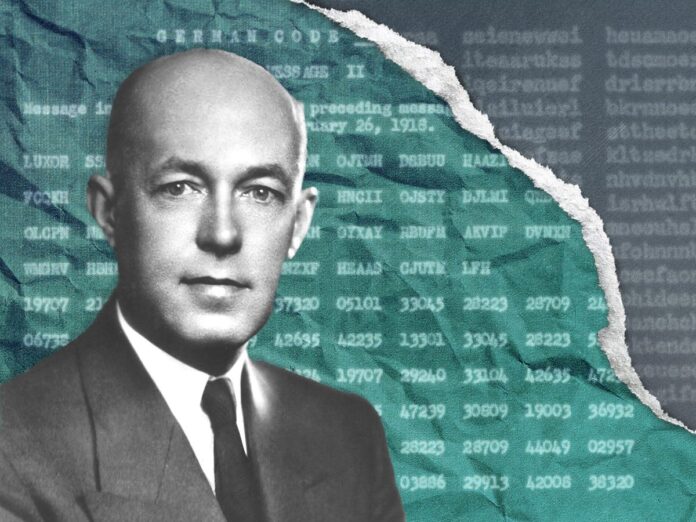

Yardley, circa 1917/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1a/d3/1ad32131-05c1-458b-ba17-914292951994/max1200.jpg)

Yardley was born in Worthington, Indiana, on April 13, 1889. After high school, the young man with a knack for mathematics joined the State Department as a code clerk and telegrapher. Employees were responsible for handling encryption and decryption of sensitive diplomatic messages sent between Washington, D.C. and U.S. embassies, consulates and legions worldwide. Working the night shift, the onetime president of his graduating class decrypted copies of codes obtained from local telegraph operators. Then, one night in 1916, he claimed to have solved a 500-word coded message between President Woodrow Wilson and Colonel Edward M. House in less than two hours.

Disturbed by the ease with which he’d broken the president’s code, Yardley compiled a 100-page memorandum titled “Solution of American Diplomatic Codes” and presented it to his superior. The man was shocked at first, Yardley wrote, but “he seemed content to let the matter drop, assuming the hopeless view that nothing is indecipherable.” As the U.S. geared up to enter World War I in the spring of 1917, Yardley decided to offer his skills to a different sector of government: the Army.

That June, Yardley was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Signal Officers’ Reserve Corps. The Army soon tapped the rising star to head MI-8, its newly formed wartime cryptology office. Initially working with only two assistants who knew nothing about cryptology, Yardley soon expanded the organization into five distinct subsections, employing more than 150 people. The MI-8 now consisted of Code and Cipher Compilation, Communications, Shorthand, Secret Inks, and Code and Cipher Solutions.

By the last few months of the conflict in 1918, Yardley’s agency was indispensable to the American war effort. MI-8 was besieged by messages, postcards and letters from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Post Office Department, as well as commercial telegraph and cable companies. “At one time, over 2,000 letters a week were tested for secret writing,” Yardley later boasted. The State Department also ensured that the bureau was busy deciphering intercepted telegrams, radio messages and mail from various countries, allied and enemy alike. The latter proved particularly tricky because the office had to remove and read the messages without arousing suspicion. Yardley and his colleagues often had to replace or duplicate official seals.

A cipher letter found on Pablo Waberski when he was arrested in February 1918/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/d2/56d24eb9-9fba-4780-9060-8b13ab49cc5d/screenshot_2025-02-03_at_101207am.png)

The success of the secret bureau was undeniable. Along with gathering invaluable information, MI-8 helped convict one of Germany’s most elusive spies, who used the alias Pablo Waberski, and capture the Prussian aristocrat and infamous spy Maria de Victorica. Fluent in many languages, de Victorica began her undercover work for the French before switching allegiance to her father’s country of birth. While the French and British seemed unable to pinpoint her location, Yardley’s bureau uncovered de Victorica’s whereabouts by deciphering coded messages she had exchanged with her agents under an alias. Yardley sent field agents to follow a young schoolgirl who had been leaving the communications in folded newspapers for an older man at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. The man picking up the package then led Yardley’s agent to the Nassau Hotel on Long Island—and the elusive de Victorica.

After spending the last few weeks of the war in Europe, meeting with his French and British counterparts, Yardley returned to the U.S., a nation then preparing for peacetime. “When I reached Washington in April 1919, I found MI-8 in a sad state,” he wrote. “There were no funds available to hold the civilian cryptographers and clerks, and a great many of the officers were anxious to return to civilian life.”

But Yardley would not be deterred. The master cryptographer secured a meeting with the director of the Military Intelligence Corps and successfully petitioned to have the agency rolled into a permanent peacetime entity funded by the State Department and the War Department. Yardley insisted the agency was indispensable for keeping America informed as a new global partner to the long-established European powers of France and Britain. He claimed that over the previous 18 months, his group had read nearly 11,000 messages, along with an “enormous number of personal codes and ciphers submitted by the Postal Censorship.”

A 1931 newspaper article by Yardley about the Black Chamber’s efforts to capture Maria de Victorica/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/e3/67e37cde-3483-4bd8-a4e6-2dec2ddc526e/maria_de_victorica.jpg)

In the summer of 1919, the former MI-8, now officially called the Cipher Bureau, moved its headquarters to a four-story brownstone in New York City. “Practically all contact with the government was now broken,” Yardley recalled. “All the employees, including myself, were now civilians on secret payroll. The rent, telephone, lights, heat, office supplies—everything was paid for secretly so that no connection could be traced to the government.” As far as the passers-by walking past the unassuming building each day were concerned, the headquarters of the Universal Code Compiling Company housed within produced commercial code and puzzle books.

In truth, Yardley and his new group, composed of the best he could retain from MI-8, were fast at work. As the cryptologist later revealed to the public, between 1917 and 1929, the Black Chamber deciphered more than 45,000 diplomatic code and cipher telegrams of foreign governments, in addition to solving the code books of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Cuba, England, France, Germany, Japan, Liberia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, the Soviet Union and Spain. While the methods of obtaining the telegrams were not always legal (they included stealing or photographing secret code books), this did not prevent the State and War Departments from appreciating Yardley’s work.

The Black Chamber’s most important contribution, and the highlight of its interwar existence, occurred during the Washington Naval Conference, held in the American capital from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922. The international diplomatic event, aimed at ensuring naval disarmament and addressing tension in the Pacific region following World War I, came on the heels of Yardley’s team cracking key Japanese codes. The information coming out of New York could not have been timelier. Japan was at odds with the other attendees over a proposed plan to downsize the Allied nations’ navies while maintaining the existing balance of power.

A meeting held at the 1921-1922 Washington Naval Conference/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/30/f530a9b7-feb1-4f1a-9e5b-bb19c4743de3/1476px-the_conference_on_limitation_of_armaments_washington_dc.jpg)

Though Japan publicly called for a 10-10-7 ratio of ship tonnage for the U.S., Britain and Japan, respectively, decryptions indicated that Tokyo was willing to settle for a 5-5-3 ratio. Armed with this knowledge, the American negotiators successfully pressed their demands on Japan. The Black Chamber received a monetary bonus, while Yardley was awarded the Army’s highest noncombat decoration, the Distinguished Service Medal.

The agency began to decline as the nation continued to move on from World War I. Commercial telegraph and cable companies balked at passing along private messages during times of peace, and a reduced budget in 1924 left Yardley with a skeleton staff. When President Herbert Hoover took office in 1929, his new secretary of state, Henry L. Stimson, began paying close attention to the Black Chamber. “Despite all our precautions … someone, or some government, suddenly became interested in our secret activities and went about learning what they could in the manner I knew they would follow, for I had not been connected with espionage all these years for nothing,” Yardley wrote.

The mysterious woman Yardley encountered at the bar in New York may well have been working for the federal government. It was apparent to the cryptologist that someone was targeting him, perhaps because he had unlimited permission to spy on the nation’s allies and foes alike. Stimson was said to have summed up his feelings about the Black Chamber with a pithy statement: “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail.”

The Black Chamber officially shut down on October 31, 1929. Yardley and his staff received three months of severance pay, and their files and records were transferred to the new Signal Intelligence Service, the Army’s predecessor to the NSA, which was now openly funded by the American government.

A 1945 photo of Henry L. Stimson, who served as secretary of state under Herbert Hoover/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/d5/59d5494c-8c6a-4900-b6e2-c29e2029e43f/1344px-photograph_of_secretary_of_war_henry_stimson_evidently_arriving_at_the_white_house_for_a_cabinet_meeting_-_nara_-_199142.jpg)

Yardley’s dismissal coincided with the start of the greatest economic depression America had ever seen. The onetime head of the most covert American agency now found himself unemployed, without an official civil service record or retirement benefits. “Never a saver,” wrote biographer David Kahn in The Reader of Gentlemen’s Mail: Herbert O. Yardley and the Birth of American Code-Breaking, “he had few or no resources to fall back on.”

In need of a way to support his wife and son, Yardley, in an act of desperation in June 1930, “sold the Japanese Embassy in Washington the information that the U.S. had broken the Japanese codes and read their messages for a considerable number of years, together with his methods of solution,” according to a now-declassified memorandum prepared for the deputy director of central intelligence in 1967. In exchange for $7,000 (around $130,000 today), the cryptologist assured his newest customers that he would not make the information public or available to others. Then he moved his family back to his home state of Indiana and began working on a tell-all book.

Yardley “sold his soul for his book,” Kahn wrote. “He exaggerated his successes in his official reports and in his book, though he was honest in minor personal matters. Yet … he told stories well. People liked him.”

Yardley poses with a copy of The American Black Chamber./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/c1/6ec1f992-1c51-4c61-bc30-f361e1895565/chamber.jpg)

The cover of the 1981 edition of The American Black Chamber/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/38/a23862c8-fa43-4605-99ce-a1213aa13630/screenshot_2025-02-03_at_101504am.png)

The publication of The American Black Chamber on June 1, 1931, as well as three preceding articles in the Saturday Evening Post, embarrassed the Japanese. Their nation now appeared vulnerable and gullible in the eyes of the world—and they’d been cheated out of $7,000. Worst of all, admitting to paying the bribe would only exacerbate the ridicule. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the NSA discovered evidence of the transaction. Meanwhile, the book became a national best seller in Japan. The Japanese government promptly purchased more than 100 copies of Yardley’s book, sending it to embassies and legations to encourage them to strengthen their codes.

The U.S. government was just as blindsided. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, had suspected that Yardley might have kept some classified documents after his forced resignation. But nobody, not even the FBI, had been prepared for Yardley’s exposé. In a desperate scramble to control the inevitable fallout, the government denied the Black Chamber’s existence, Yardley’s employment in any such organization and the claims that the U.S. had broken any Japanese codes.

But it was too late. Twelve years of the agency’s top-secret communication intelligence, including its methods, were open to anyone who spent $3.50 on Yardley’s book. Yardley reportedly told a friend that his financial situation had left him no choice, though he felt the government’s lousy treatment of him had made the decision easier. By closing his bureau, Yardley insisted (rather disingenuously), the government had left the cryptoanalysis business, so the secrets he had to offer were now harmless.

In the years immediately following, Yardley remained in Indiana, working on a series of other books and a commercial secret ink. Relying on his newfound fame, the spymaster published Yardleygrams, a collection of cryptologic puzzles designed to teach readers how to become amateur cryptologists. He followed it with two spy novels loosely based on his exploits in the Black Chamber.

By 1932, however, the security and censorship circle had begun to close around Yardley. The Justice Department warned publishers against accepting his newest controversial nonfiction book. Titled Japanese Diplomatic Secrets, 1921-22, the text centered on the Washington Naval Conference and was ghostwritten by Marie Stuart Klooz, an acquaintance of Yardley’s literary agent. When Yardley submitted the manuscript to Macmillan in February 1933, a U.S. marshal seized and impounded it under the Espionage Act of 1917, which prohibited taking secret documents. Yardley’s short-lived career as a leaker of government secrets was over.

In response to The American Black Chamber, the State Department convinced the House Judiciary Committee to propose a bill “for the protection of government records” in March 1933. Nicknamed the Secrets Act, the resulting legislation established stricter regulations for handling classified information, provided a legal framework for protecting government records of national security and declared it a criminal offense to disclose classified information without authorization. Although minor adjustments have been made over the years, the act, Section 952 of Title 18, remains part of the Crimes and Criminal Procedure of the U.S. Code.

More recently, Title 18 was used in the legal proceedings against Snowden, the former CIA employee and contractor who in 2013 disclosed highly classified information about NSA surveillance. By then, Yardley’s story and the ensuing scandal had long been buried in the annals of American history. But that didn’t mean the Justice Department ever forgot about Yardley. The former head of the Black Chamber went on to become a Hollywood technical adviser on spy movies, and he even worked stints for the Chinese and Canadian governments in cryptology advising roles. But the FBI, the NSA and the CIA never took their eyes off him. Stifled by the newly enacted Secrets Act and the pressure exerted on companies by the Justice Department, Yardley was never again able to publish his intelligence-related stories. The cryptoanalysis pioneer had become a persona non grata, and China and Canada eventually let go of his services amid mounting international pressure. (Yardley detailed his work for Chiang Kai-shek in a book titled The Chinese Black Chamber, but this follow-up was withheld from publication for decades, only to be released posthumously to little fanfare in 1983.)

Yardley was able to reinvent himself yet again in 1949, beginning a quasi-successful career at the Public Housing Administration. In the early 1950s, he tried to republish The American Black Chamber, but the publisher flatly declined. Ballantine Books republished the text in 1981 as part of its Espionage/Intelligence Library, but it hasn’t been reprinted since. The last of Yardley’s books to be published during his lifetime was The Education of a Poker Player, a 1957 nonfiction work that one reporter later deemed “arguably the most successful book about poker ever written.”

Yardley died on August 7, 1958, at age 69. He was a pariah in official American government circles until the very end.