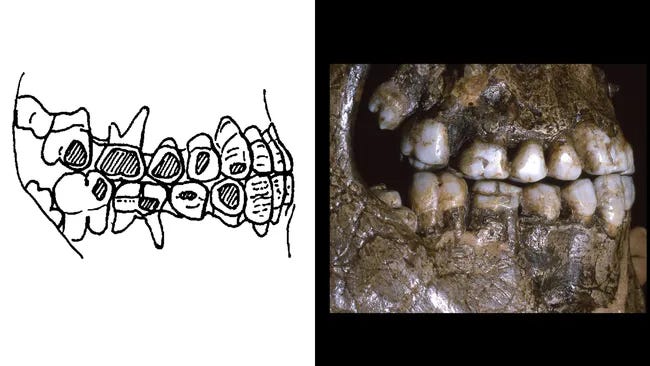

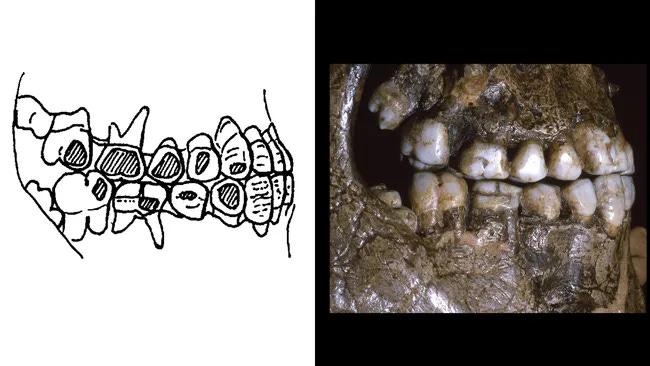

For decades, archaeologists studying the remains of Central Europe’s Pavlovian culture—hunter-gatherers who lived between 25,000 and 29,000 years ago—have puzzled over an unusual feature in their teeth. Unlike typical wear patterns that form on the biting surfaces due to chewing, these ancient individuals displayed a distinct type of enamel erosion on the cheek-facing sides of their teeth.

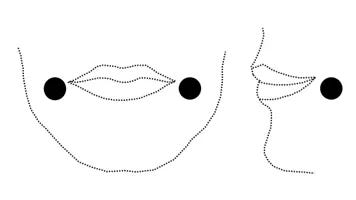

A new study suggests an unexpected explanation: labrets, or cheek piercings.

The research, published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, was conducted by John Willman, a biological anthropologist at the University of Coimbra in Portugal. He argues that these dental patterns match those seen in cultures known to wear labrets, a type of piercing that rests against the lower lip or cheeks. The study suggests that children as young as 10 may have worn labrets, and that they may have been tied to group identity, status, or rites of passage.

“There was a long history of discussion of the strange wear on the canines and cheek teeth of these individuals,” Willman explained. “But no one really knew what caused the wear.”

Labrets have a long history in human cultures. Indigenous communities across the world—including groups in North and South America, Africa, and Siberia—have used them as a form of adornment for thousands of years. However, direct evidence for their use in Paleolithic Europe has been lacking, largely because the materials used—wood, bone, or leather—would have decomposed over time.

Willman’s study doesn’t rely on the presence of labrets themselves. Instead, he examined how wear patterns on the teeth differed by age. The results suggest that labret use may have begun in childhood, since some baby teeth showed early signs of wear. Over time, the extent of wear increased, likely corresponding to larger labrets being worn in adulthood.

“In the case of the Pavlovians, having labrets seems to be related to belonging to the group,” Willman said. The variation in tooth wear, he suggested, “may relate to individual choice, different life experiences that ‘earn’ labrets during life, like going through puberty or marriage.”

While body modification is a deeply personal and cultural practice, it sometimes comes with unintended physical consequences. In modern contexts, labrets can cause dental shifting if the jewelry presses against the teeth for long periods. Willman found evidence that some Pavlovian individuals exhibited signs of dental crowding, suggesting their teeth had been subtly pushed over time—almost like “reverse braces.”

“Piercings can cause a tooth to move,” he noted. “Some individuals have dental crowding, which I interpreted as an effect of having labrets resting against the teeth for long periods of time.”

This adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that Ice Age hunter-gatherers engaged in complex personal adornment. Despite the harsh environments they lived in, they took time to modify their appearance, reinforcing social bonds and expressing group identity through ornamentation.

April Nowell, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Victoria who was not involved in the study, emphasized the significance of the findings.

“As someone who studies Ice Age adolescents, I find this study very exciting,” Nowell said.

She pointed out that most of the organic materials used in daily life by hunter-gatherers have long since disappeared, making it easy to underestimate the sophistication of their cultures.

“Willman’s study offers a window onto a long-disappeared behavior—it gives scientists a way of studying personal and social identity as they change throughout a person’s life,” Nowell added.

Moving forward, the study raises an important question: Have archaeologists been overlooking evidence of Ice Age labrets? Nowell suggested that it may be worth revisiting artifact collections from Pavlovian sites to see if any previously unremarkable objects could have actually been body ornaments.

If confirmed, the presence of labrets among Ice Age Europeans would add to the growing understanding that early humans were not only practical survivalists but also individuals who valued personal and cultural expression, even in the harshest of climates.

-

Nowell, A. (2016). “Growing Up in the Ice Age: Fossil and Archaeological Evidence of the Lived Lives of Plio-Pleistocene Children.” Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199936125.001.0001.

-

d’Errico, F., & Vanhaeren, M. (2009). “Earliest personal ornaments and their significance for the origin of language debate.” PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0902466106.

-

Hoffmann, D. L., et al. (2018). “U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art.” Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.aap7778.