Last week I had the pleasure of once again assisting the research staff at PBS’s Finding Your Roots with interpreting a document that relates to my scholarship on the Black Confederate myth and the history of Confederate body servants or camp slaves.

The document in question is one that I know very well. In the 1920s five former Confederate states issued pensions to a small number of former body servants. These documents are easy to access and have been intentionally misrepresented by organizations like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and others, who seek to use these files to prove that Black men fought as soldiers for the Confederacy and that the preservation of slavery was incidental to the goals of the Confederate nation. Even a cursory glance at these files indicates that these men were understood as “servants” or former slaves.

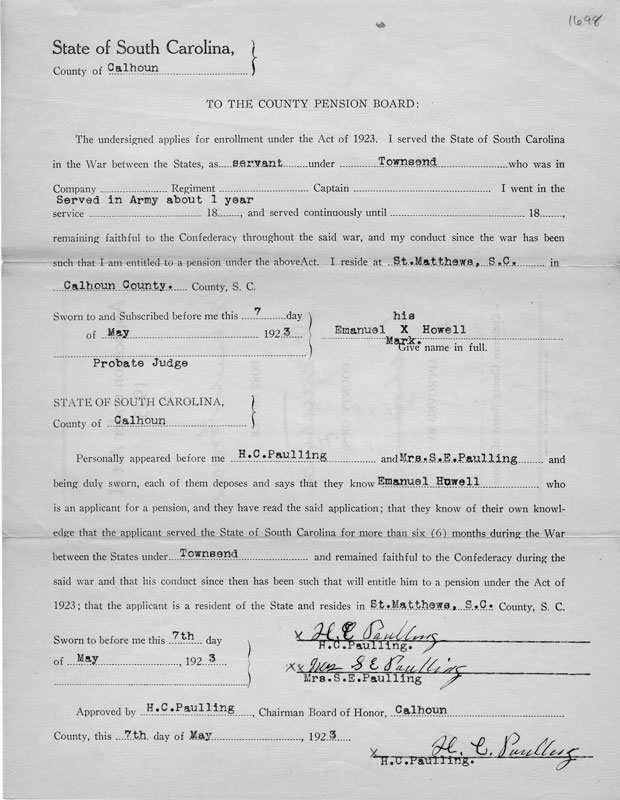

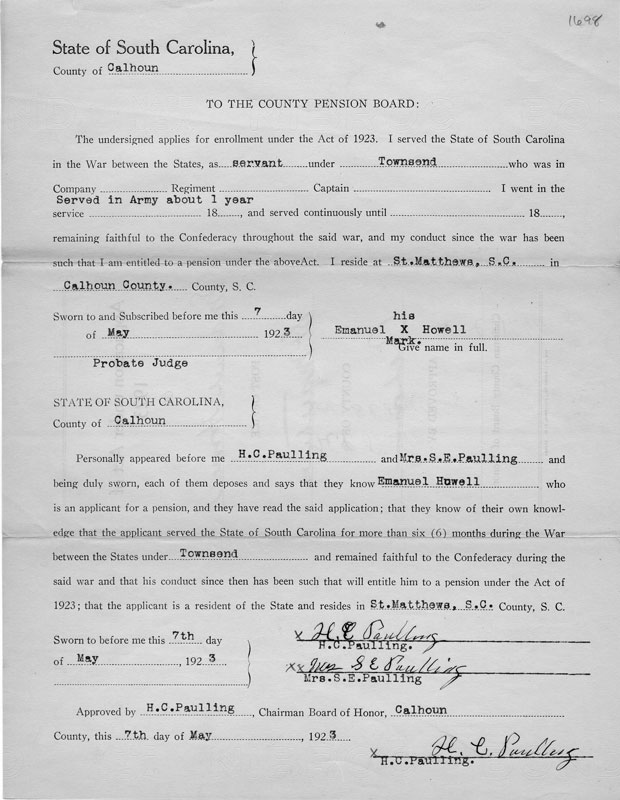

Here is the pension file from South Carolina for Emanuel Howell that we discussed:

Paulling, Hamilton 1923 (May 7) Civil War Pension Application for Emanuel Howell (former enslaved man of Paulling family), South Carolina S126088, SC State Archives archivesindex.sc.gov

Paulling, Hamilton 1923 (May 7) Civil War Pension Application for Emanuel Howell (former enslaved man of Paulling family), South Carolina S126088, SC State Archives archivesindex.sc.gov

I guided the team through the document emphasizing Lost Cause themes such as the reference to the “War between the States” and especially the clause that asks the applicant to swear “remaining faithful to the Confederacy.” Not surprisingly the research team had already noted these points, but what they missed was what followed in the very same sentence.

Former slaves didn’t just have to demonstrate their loyalty to the Confederacy, but that their “conduct since then has been such that will entitle him to a pension.” What could this possibly mean?

Understanding this involves placing the document in proper context. The First World War had just recently ended with the United States having made the world “Safe For Democracy.” Black soldiers had come home wearing their uniforms and carrying weapons and were viewed as a threat by white Americans, especially in the South.

White control by the 1920s had been solidified through the passage of new state constitutions that limited Black voting, segregation laws that separated the races in virtually every aspect of life, and through extra-legal methods such as lynchings, but there was always the fear of Black activists and other threats to this fragile racial status quo.

What I found in the course of my research is that former body servants were singled out throughout the post-Civil War period for knowing their place in a white dominated world. They were praised for not voting Republican during Reconstruction and remaining loyal to the Democratic Party. Some attended Confederate veterans reunions and told stories about how they rescued their former masters on battlefields or how they bravely brandished a rifle to shoot at the enemy.

In short, they were celebrated in order to contrast their behavior with a younger generation of African Americans who continued to push for civil rights through the Republican Party and other organizations.

These are the men who were awarded pensions at the very end of their lives.

But there is something else about these documents that I am now able to see much more clearly in light of the public discussion about Critical Race Theory. The documents and the pension program itself helped to reinforce white supremacy at a crucial point. Each applicant was forced to perform for the state by declaring and accepting, in front of representatives of the local community, his second class status, which in turn legitimized the systemic racism within the state.

Finally, we need to acknowledge the extent to which the state leveraged the power of history as a means to maintaining and justifying its racist legal infrastructure and how it relied on the very individuals, at an incredibly vulnerable time in their lives, to ensure its continuation.