More than 46,000 years ago, deep within the caves of what is now northern Spain, a silent drama unfolded between humans and the great beasts of the Ice Age. The remains of their existence—fragments of bones, scattered tools, and enigmatic carvings—have long been studied by archaeologists. But now, an unprecedented glimpse into this vanished world comes not from the bones themselves, but from the very dirt that once surrounded them.

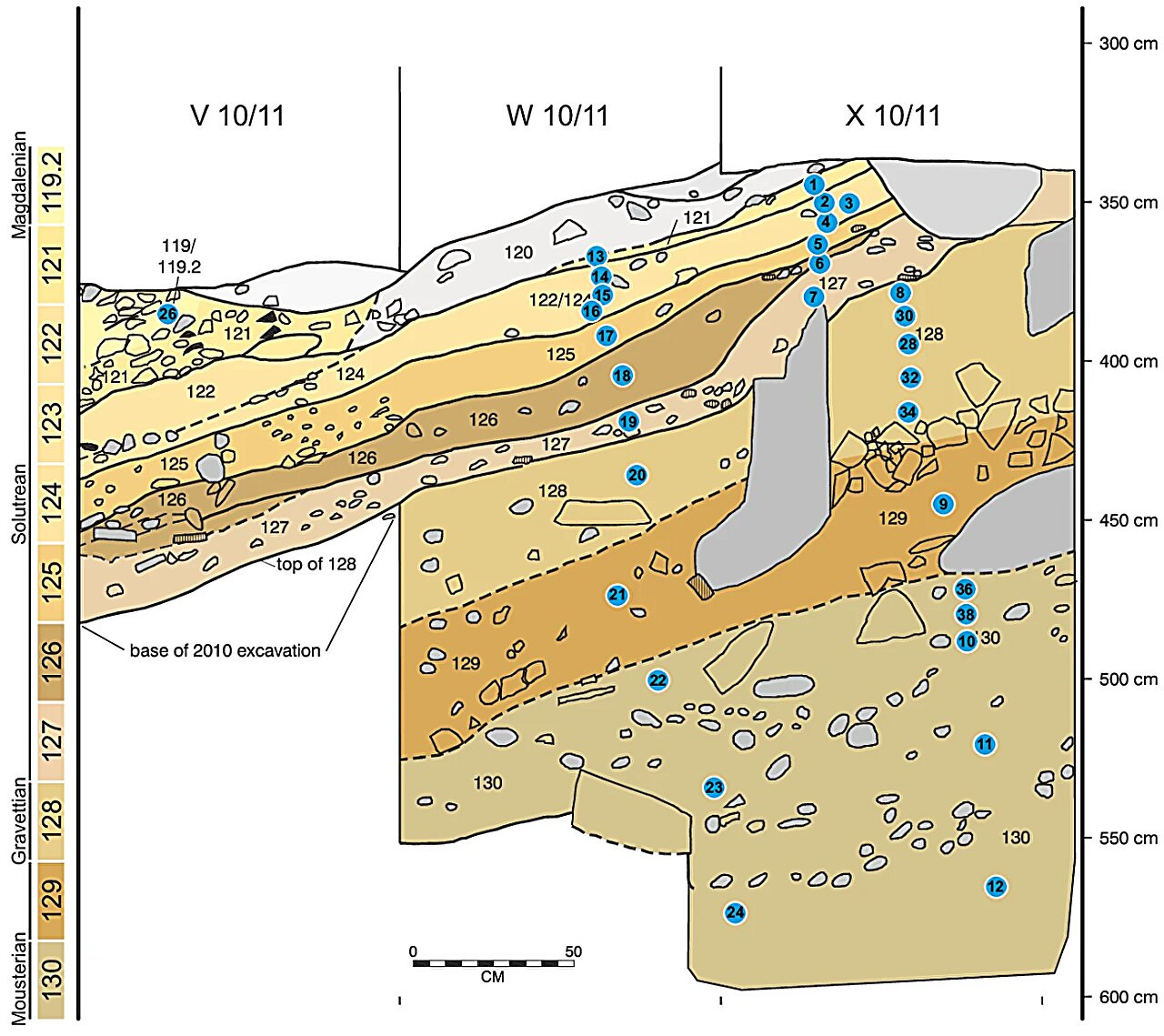

A new study, published in Nature Communications, harnesses the power of sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA) to reconstruct the genetic history of both humans and animals at El Mirón Cave, a crucial Ice Age refuge in Cantabria, Spain. The research team, led by Pere Gelabert, Victoria Oberreiter, and Ron Pinhasi, has revealed surprising new insights into the movements, interactions, and persistence of species through the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). This work does not just add to our understanding of the past—it rewrites it.

For centuries, the study of prehistoric life has relied on the fragile remnants of bones and artifacts. However, in the cold, dark recesses of caves, DNA lingers—trapped in layers of sediment. The researchers at El Mirón extracted this ancient genetic material to uncover the presence of humans, wolves, cave lions, and even hyenas, whose very existence in Iberia at this time had previously been uncertain.

“We don’t need bones,” says lead author Gelabert. “The results show that several animals not represented by bones from the dig were present—either once living in the cave or as carcass pieces.”

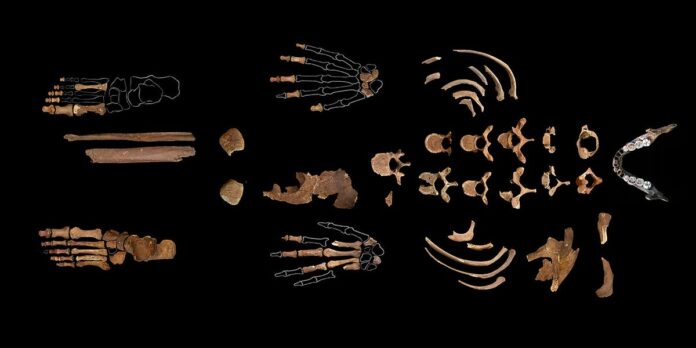

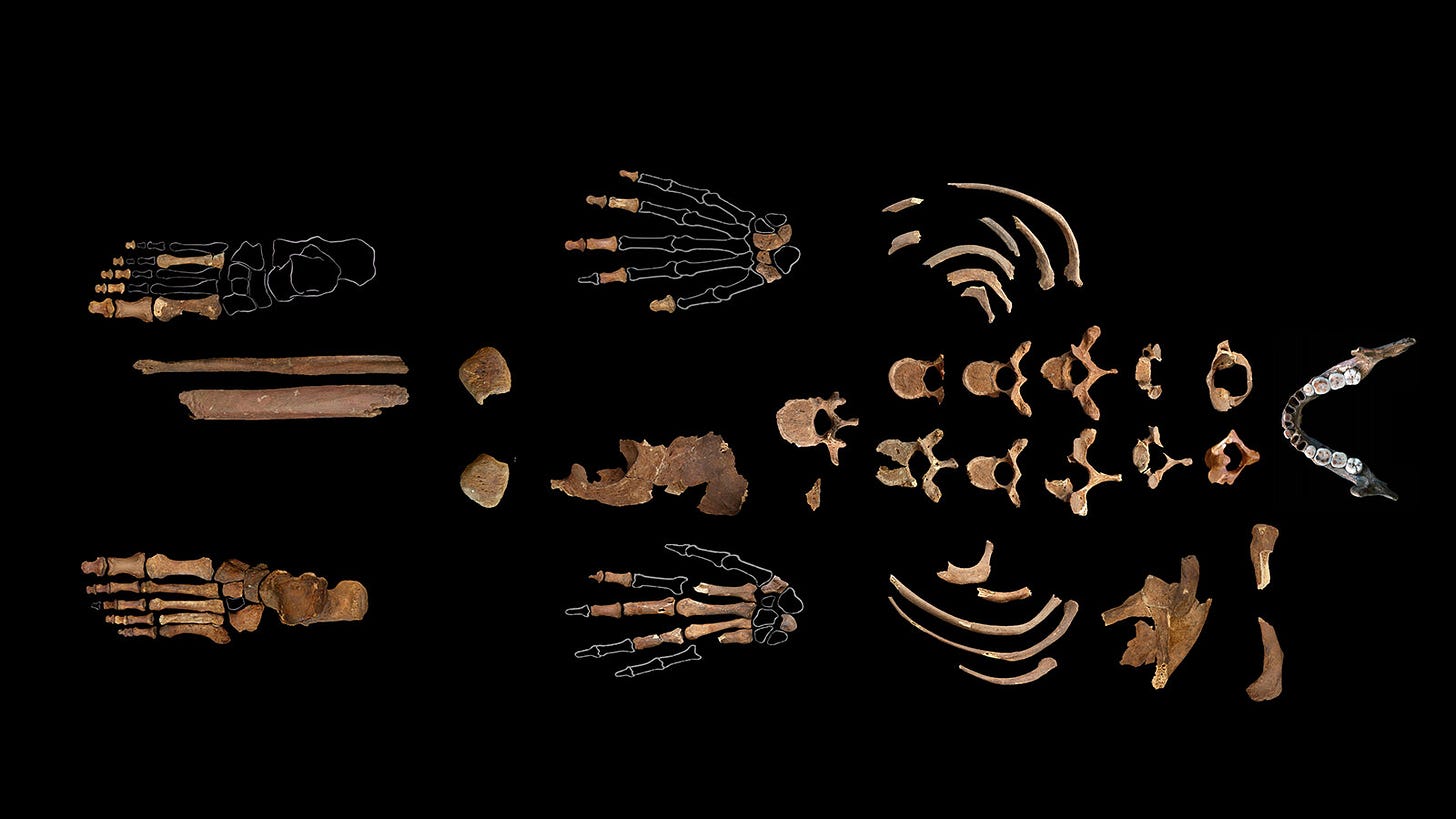

By using DNA extracted from sediment layers spanning 46,000 to 20,000 years ago, the researchers reconstructed a vivid ecological timeline. They identified 28 animal taxa, 15 of which had not previously been found at the site. More importantly, the study provided evidence that humans and large carnivores—like hyenas and leopards—coexisted in Iberia for much longer than previously thought.

Among the most stunning revelations was the recovery of three human mitochondrial DNA sequences from sediment dating to the Solutrean period (roughly 24,500–22,000 years ago). These genetic signatures match the so-called “Fournol cluster” of Gravettian ancestry, suggesting that a distinct population survived in this region through the Last Glacial Maximum.

“These were the people whose range had contracted southward during the climatic crisis,” explains Gelabert. “They contributed to the genetic makeup of later populations, including the famous Red Lady of El Mirón.”

This discovery challenges the long-held belief that early European populations were completely displaced by later waves of migration. Instead, the findings suggest that the Iberian Peninsula served as a genetic refugium—a sanctuary where prehistoric groups endured the harsh Ice Age before spreading out once the climate warmed.

While human DNA was found, so too were the genetic signatures of an impressive array of Ice Age creatures. The research provides the first genetic confirmation that hyenas persisted in Iberia into the Magdalenian period (21,000–12,000 years ago), much later than previously thought. This suggests that human groups may have had to compete more fiercely for caves and hunting grounds than once assumed.

Leopard DNA from the sediments also paints a surprising picture. The genetic sequences from El Mirón Cave show a close affinity with leopards from the Caucasus rather than other European sites, hinting at previously unknown migration routes or population mixing.

Meanwhile, the presence of wolves, dholes (wild Asiatic dogs), and even woolly mammoths speaks to a rich ecosystem, frozen in time.

“The ability to extract DNA from dirt makes it much more possible to study ancient animals and humans,” Gelabert notes. “We now know who the predecessors of the Red Lady were, confirming evidence from other sites.”

The ability to extract DNA from sediments is revolutionizing the study of human and animal history. While bones remain invaluable, they represent only a fraction of the life that once inhabited a given site. This study demonstrates that a more complete picture can be built from the very ground beneath our feet.

Still, the study comes with its challenges. Contamination is a concern, and linking DNA to specific individuals or species requires careful verification. Moreover, while mitochondrial DNA provides valuable lineage information, nuclear DNA—offering deeper genetic insights—remains much harder to recover.

El Mirón Cave continues to surprise, revealing that its inhabitants—both human and animal—were more diverse, persistent, and interconnected than previously thought. This study highlights the resilience of prehistoric populations and the hidden histories still waiting to be uncovered.

Future work will aim to extract nuclear DNA, offering a more complete genetic picture of these Ice Age communities. But for now, the sediment of El Mirón whispers secrets long buried—proof that the past is still very much alive in the soil beneath our feet.

-

Gelabert, P., Oberreiter, V., Straus, L. G., et al. (2025). A sedimentary ancient DNA perspective on human and carnivore persistence through the Late Pleistocene in El Mirón Cave, Spain. Nature Communications, 16(107). DOI:10.1038/s41467-024-55740-7.

-

Vernot, B., et al. (2021). Unearthing Neanderthal population history using nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from cave sediments. Science, 372(6542), eabf1667. DOI:10.1126/science.abf1667.

-

Zavala, E. I., et al. (2021). Pleistocene sediment DNA reveals hominin and faunal turnovers at Denisova Cave. Nature, 595(7869), 399-403. DOI:10.1038/s41586-021-03675-0.

-

Gelabert, P., et al. (2021). Genome-scale sequencing and analysis of human, wolf, and bison DNA from 25,000-year-old sediment. Current Biology, 31(17), 3830-3836. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.023.