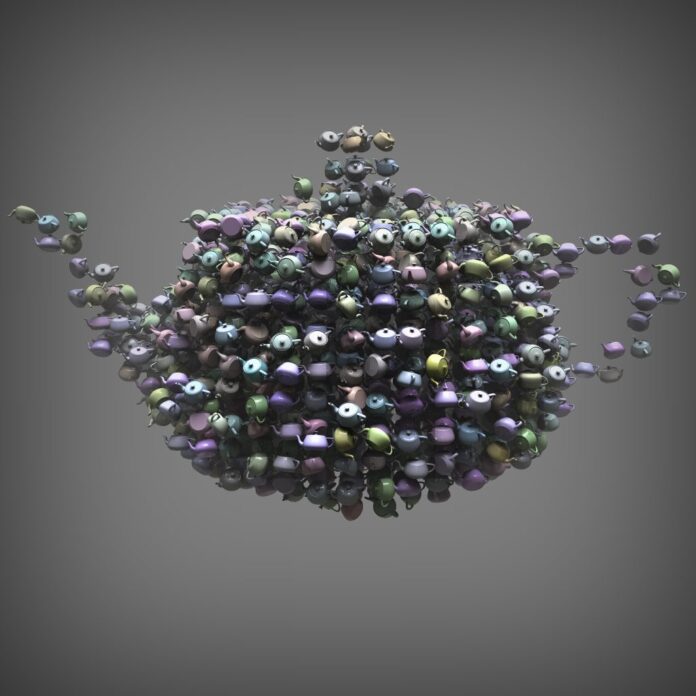

Figure 1. Render of Houdini scene featuring the Utah teapot which is available as an “off-the-shelf” object in most contemporary 3D software packages. 2024 Gina Moore.

Found in various industries including film, advertising, games, and visualisation, computer graphics (CG) are ubiquitous and largely invisible in our contemporary screen world. In his book Image Objects; An archaeology of Computer Graphics, Jacob Gaboury describes how computer graphics have also influenced our physical world. Looking around right now, I can see buildings, chairs, bicycles, and a laptop and, having recently read Gaboury’s book, I can imagine how each of these objects has been “produced, reshaped, and transformed by their encounter with computational images” (p25).

Not just images – One of the book’s key points is that computer graphics are not just images displayed on a screen. CG and the physical objects they produce elude binaries such as material-immaterial, and physical-digital; they are images and objects, or “image objects”. Today, computer graphics are so sophisticated and so much a part of our world that we don’t recognise their ambiguous ontological status or vast sphere of influence. To reveal this complex relationship, Gaboury returns to the early days of computer graphics, focusing on the 30-year period between 1960 and 1990. This is the era before digital visual effects took off in film and before computers were easily accessible.

From tool to medium – As well as making its mark on our physical environment, this book argues that computer graphics played a significant role in the development of contemporary interactive computing. For animators such as myself, the computer is a medium because we can interact with the machine through images and text. Gaboury’s book reminds us that computers were originally more like calculators than the interactive devices we use today, i.e. they were fed information and left alone to calculate answers. In the 1960s many computer scientists regarded graphics research as a frivolous activity, but people such as Ivan Sutherland could see its crucial importance even at this early stage. Gaboury explains that “For Sutherland, visual images were essential tools for understanding complex problems” and they served as the interface between human operators and computing machines (p33). Along with David Evans and others from the University of Utah, Sutherland is one of the key figures in this book.

Structure – The book’s five chapters each focus on a different object which has been significant in computer graphics research. Chapter one describes “the hidden surface problem” which, according to Gaboury, presented a bigger challenge to researchers than perspective projection. Chapter two focuses on the frame buffer and tells a history of the computer screen, describing various technical and conceptual objects including the cathode ray tube, the line, and the grid. Chapter three focuses on one of the first simulated objects, the Utah teapot, which was shared among researchers and used to test various algorithms for simulating materials, lighting, etc. The focal point of chapter four is object-oriented programming, which is a computational strategy derived from common understandings of objects in the physical world. According to Gaboury, at the heart of CG and computing more broadly is a “theory of objects” and this chapter describes “the way computer science imagined the world to be structured and in turn came to structure the world” (p129). The focus of chapter five is the GPU (graphics processing unit) which Gaboury says is an object that brings together the entire history of CG. It’s interesting to note the contemporary dominance of the GPU which perhaps supports Gaboury’s point about the centrality of graphics in the field of computing.

Summary – As an “archaeology” of computer graphics, this book digs up and describes various historical objects that make contemporary computing possible and tells the story of significant people, institutions, and embodied practices. Like recent publications by Alan Warburton (“RGBFAQ”, 2020) and Jordan Gowanlock (“Unpredictable Effects Nonlinearity in Hollywood’s R & D Complex”, 2021), this book takes us behind the rendered image and reveals the complex, reflexive relationship between computer graphics and a world shaped by computation. The book covers a lot of ground and is compelling but there were times when I found the long technical descriptions difficult to understand. While reading, I also craved more explicit definitions of the term “object”. Like Object-Oriented Ontology, the word is used very broadly in this book, which sometimes makes it difficult to fully grasp some of the author’s points. Despite at times being difficult to follow, the book communicates a convincing argument for the pivotal role that computer graphics have played in shaping our contemporary world, including digital practices and physical objects. In short, even if you don’t understand everything written in this book, reading it will prompt you to see screen images and the physical world around you in a new way.

Dr. Gina Moore is a visual artist, animator, researcher, and lecturer in the Animation program at RMIT University, Australia. With a special interest in 3D animation and VFX, Gina’s work investigates assumptions implicit in 3D animation software and explores experimental techniques. Ultimately, she is interested in emerging animation technologies and practices that disrupt anthropocentrism and promote ecological awareness.