In my capacity as a fellow in our faculty research center, I’ve been doing a

lot of support work for the unexpected shift to learning-at-a-distance.

At my uni, very few of us have experience teaching online. The faculty

(generally) aren’t especially enthusiastic, and there hasn’t really been a lot

of institutional support. So, I wasn’t surprised when most of the

questions I was fielding took the form of: “I do X in my class. How

can I do X online?” Not surprised because that’s the ideological

frame distance education has relied upon: an exact homology between offline-

and online teaching, with the physical classroom replaced by the discussion

board, the lectures by videos. But actual online courses (not our band

aid efforts to stitch together something in a few days) are structured very

differently than their physical counterparts. The best classes maximize

their digital affordances and don’t try to simply “reproduce”

face-to-face education.

Something similar has happened with ethnography. I have read dozens of

semi-panicked posts: if I can’t go into the field, perhaps I can go into the

digital field? Well – there have been several, thoughtful posts from

digital anthropologists on this sentiment, including a recent one in GeekAnthropologist. Reading these, though, I can’t help but notice that these

would-be digital anthropologists don’t really want to be digital at all.

And they’re not really proposing digital anthropology. If you’re studying

the lives of people in their (physical) communities, can you really do digital

anthropology? In other words, if people are undertaking online/offline

lives (whether under quarantine or not), are those lives best understood

through digital anthropology? Or are you talking about what my colleague,

Matthew Durington, and I have called “networkedanthropology“?

In networked anthropology, we acknowledge the skein of digital and physical

connections in people’s lives, and we try to recognize and enable the

capacities of people to represent those lives through networked,

media platforms that make sense to them.

In a quarantined world, what’s

missing from the social scene? With regards to the production of

ethnography, at least one element is missing: the anthropologist. But

only that. Even without the anthropologist, social and cultural life

continue. And more than that–the documentation and theorization of

social and cultural life continues as people record and comment on the things

that happen in their lives and in their communities. In this sense,

networked anthropology is about capitulation–perhaps we really weren’t that

important anyway? But we can certainly help people in their own efforts

to represent and communicate their identities and communities, and this is, I

think, what (at least some) of our colleagues should be doing.

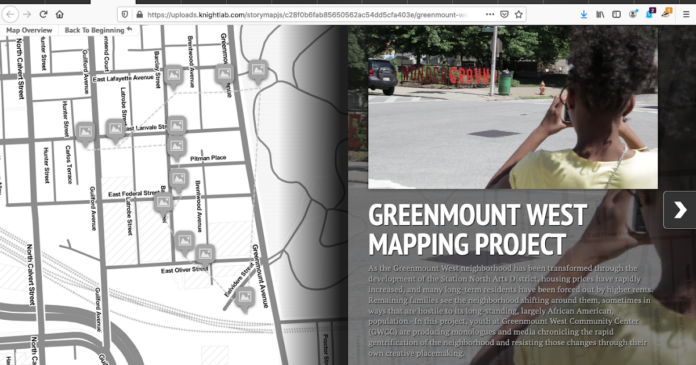

Last summer, we worked on a project in a small neighborhood in Baltimore

undergoing rapid gentrification that was leading to the displacement of a

long-standing community of African American residents. Collaborating with

children at a community center, we helped them (co)produce maps, photographs,

video and audio interviews that we put together for an app tour, an exhibit and

a performance. It was a great project to work on, and the article that we

are submitting on this includes all of them as co-authors. In light of

our present pandemic, and in the interest of protecting communities from us, it occurs to me that we (me and Matt Durington) didn’t really

need to be there at all. Sure – we needed to talk to people and see what

they were up to. In the end, though, the images and interviews are

produced by people in the community. My point: if we never actually

stepped foot in that neighborhood, that would not make it digital

anthropology. We would just be doing networked anthropology –

anthropology with people who were physically (not virtually) in their

communities.

I don’t know when the infection rates and death toll of the pandemic will

subside. But it seems likely that we will not be able to undertake our in

situ research for some time. Even if we can go into the field, it may be

in fits and starts, with pandemic flare-ups mandating our social distancing

once again. But just because we are not in situ doesn’t mean that people

in the communities where we work aren’t in situ! By now, we are all used

to that peculiar hypocrisy in anthropology that decries colonization and its authorizing

gaze, but that still seems to insist on presence in order to undertake

anthropology. Perhaps enough of

that?