Art

Maxwell Rabb

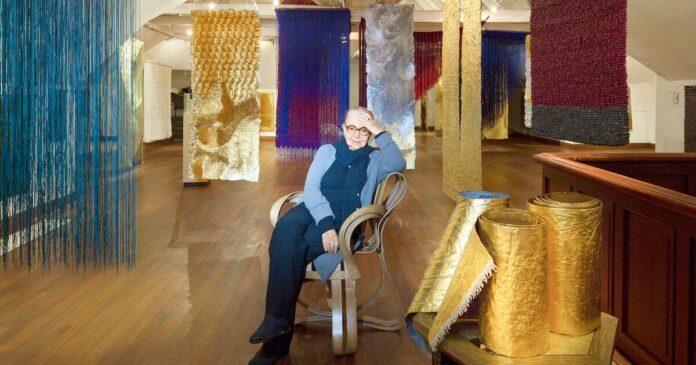

Portrait of Olga de Amaral at Casa Amaral, Bogotá, Colombia, 2013. Photo © Diego Amaral. Courtesy of the Fondation Cartier.

Colombian artist Olga de Amaral first discovered her love for textiles in the folds of her mother’s handiwork. Born in Bogotá in 1932, she was the eldest of eight siblings.

“I have a memory…that stayed in my mind: my mother caressing various types of fabrics, such as ruanas or blankets,” said Amaral, referring to the poncho-like garment made from heavy wool common in the mountains of Colombia. “She would run her hand over them, and the materials would come into direct contact with her skin. On other occasions, she would pick up objects and just watch them, and she passed on to me that appreciation for form, texture, and color.”

Handmade fiber, horsehair, plastic, and gold: The materials interlaced into Amaral’s textiles testify to her meticulous, lifelong attention to texture and form. For six decades, her sculptural, often colossal work has challenged categorizations of “craft” and “art,” an approach that has also brought newfound recognition for contemporaries in textile art Sheila Hicks and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Even at 92, Amaral is actively producing new pieces in her studio, such as the “Brumas.” In these works, she paints geometric patterns directly onto cotton threads, creating diaphanous, three-dimensional forms that are meticulously arranged to shimmer and sway, not woven but constructed.

Olga de Amaral, installation view at the Fondation Cartier, 2024. © Marc Domage. Courtesy of the Fondation Cartier.

Twenty-three of the “Brumas” are currently hanging from the ceiling at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain as part of Amaral’s first European retrospective, on view until March 16th. This exhibition is the latest of a growing list of milestones since 2020, preceded by notable solo exhibitions at Lisson Gallery in London and New York, a traveling U.S. retrospective in 2021, and a spot in the 60th Venice Biennale exhibition last year.

The exhibition at the Fondation Cartier shows her standout contributions to textile art’s development, featuring more than 80 works created between the 1960s and the 2020s. “What makes her work particularly significant is her participation, in the 1960s, in a true revolution of textile art, making it architectural, three-dimensional, monumental, and, of course, abstract,” said curator Marie Perennès. Yet when asked about definitions such as craft and art, Amaral responded with a certain nonchalance: “I don’t think about it. It’s not one of my concerns.” What truly concerns Amaral is the work itself.

Early work

In 1952, Amaral completed a degree in architecture from the Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca in Bogotá. It was there she became interested in experimenting with texture and form.

“Architecture awakened in me an interest for observing form, proportion, and color with new eyes,” said Amaral. Inspired to construct more than just buildings, Amaral journeyed to New York City and soon enrolled in the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, renowned for its Bauhaus-inspired teachings. This creative sanctuary offered her the perfect environment to meld her modernist inclinations with a tactile medium: fiber.

“At Cranbrook, I learned about the loom, which I saw as another way of working and constructing things,” she said. “I became interested in fiber, in thread, because weaving allowed for invention.…I took everything very seriously, especially if I liked it. I would absorb everything that came my way.”

Upon returning to Colombia and establishing her life with her husband, artist Jim Amaral, Amaral helped start the textile department at the University of Los Andes in Bogotá. During this time, Amaral’s creations were predominantly traditional wall-hanging tapestries that exhibited modernist influences, particularly colorful geometric designs. As the decade progressed, however, she began to create larger works with unconventional materials, exemplified by her five-foot-tall piece Luz Blanca (1969), comprising hundreds of plastic sheets.

Artistic influences

Olga de Amaral, installation view at the Fondation Cartier, 2024. © Marc Domage. Courtesy of the Fondation Cartier.

In the early 1970s, Amaral made a massive leap in scale. Her “Muros tejidos (Woven Walls)” series consisted of colossal vertical works constructed from pre-woven rectangular strips made from wool and horsehair. These works debuted at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York in 1970. Her six-story weaving El Gran Muro, which was installed in 1976 in the lobby of the Westin Peachtree Plaza in Atlanta, epitomized the architectural scale of her new style of work, and earned her international attention.

At this point, Amaral was already at the forefront of a group of women artists like Hicks and Abakanowicz transforming domestic handiwork into pioneering textile art, featured in a major textile exhibition at MoMA in 1969.

However, Amaral’s work also drew from her Colombian heritage. “What sets Olga de Amaral apart is that she comes from this very region, the mountainous areas around Medellín, where the colorful, geometric, and abstract textile tradition is deeply rooted,” said Perennès. “Her works also often incorporate motifs likely borrowed from pre-Columbian art—such as the spiral—as well as the use of gold, which is rooted both in Colombian ancestral art and in the colonial heritage, particularly that of Catholic church altars.”

Olga de Amaral’s golden world

Olga de Amaral, Strata XV, 2009. © Olga de Amaral. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Olga de Amaral, Círculo V-VI (dyptic), 2004. © Olga de Amaral. Photo © Juan Daniel Caro. Courtesy of Galeria La Cometa, Bogota, Colombia.

Bright color has always been vital to Amaral’s art, manifesting in the vibrant gradients of her “Brumas” series and the expansive monochromes of her “Muros tejidos.” However, the most distinctive and transformative color in her palette is undoubtedly gold. “For me, gold is the sun,” she said in a studio walkthrough with Christie’s in 2020.

Amaral recalled that she first considered gold after ceramist Lucie Rie introduced her to the Japanese technique of kintsugi, which involves repairing objects by accentuating their cracks and breakages with gold powder. Inspired by this meeting, she returned to her studio. “I bought some gold leaf to begin experimenting with. I had a basket with strips of woven fabric—I used to call them tachuelas—and I started sticking the gold on top,” she said.

Olga de Amaral, installation view at the Fondation Cartier, 2024. © Marc Domage. Courtesy of the Fondation Cartier.

Perhaps the most known of these gold-infused works is her “Estelas (Stars)” series, which she started in 1996. These hangings, some of which are on view at the Fondation Cartier, are composed of a thick layer of gesso, over which she applies acrylic paint and gold leaf, concealing all traces of the underlying fabric. The result is enormous, undulating fabric works that resemble shards of gold floating within the subdued lighting of the gallery space.

Amaral’s works create a holy, spiritual aura, with each piece honoring the exhibition environment and ancestry, as well as the vibrant colors and intricate textures she employs. Her textiles are extensions of the appreciation for form, texture, and color her mother nurtured in her as a child. “Color and shapes are everything to me,” she said.

“Texture expresses truths about the materials that things are made of, and this is why I became so interested in it,” said Amaral. “This was an inner process of observation and attraction that I was not very conscious of. I would say that, in this sense, I was simply following my instinct.”

MR

Maxwell Rabb

Maxwell Rabb is Artsy’s Staff Writer.