When you look at Greenland on a map, it appears as a vast, icy landmass, remote and untouched. But beneath its frozen surface lies a complex history of human migration, isolation, and adaptation. Now, an ambitious new genetic study has decoded the hidden story within Greenlanders’ DNA, shedding light on how their ancestors braved one of the harshest climates on Earth—and how their unique genetic makeup could shape their health today.

Led by a team of international researchers, this large-scale genomic analysis, recently published in Nature, analyzed nearly 6,000 Greenlandic individuals—an astonishing 14% of the adult population. Their findings not only rewrite the history of Inuit migration but also challenge the Eurocentric lens of modern genetics and medicine.

“Genetics is increasingly important for diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of disease. However, genetics research has been carried out predominantly in people of European genetic ancestry,” the researchers write.

Their study reveals how centuries of isolation, dietary adaptation, and recent European intermixing have shaped the genetic architecture of Greenlanders in ways that are both extraordinary and medically significant.

The genetic history of the Greenlandic Inuit is marked by an extreme bottleneck. Their ancestors, migrating from Arctic Canada less than 1,000 years ago, split into small, isolated groups along the country’s jagged coastline. Unlike in more densely populated regions, gene flow between groups was minimal. The study estimates that fewer than 300 individuals initially made the journey to Greenland, which drastically limited genetic diversity.

“The Inuit ancestors entered northwestern Greenland from Arctic Canada less than 1,000 years ago… The ancestral Inuit population went through a more severe population bottleneck than any European population, including Icelanders and Finns,” the study reports.

This genetic bottleneck led to an unusual pattern: fewer overall genetic variants but a higher prevalence of impactful, population-specific mutations. Some of these mutations appear to have provided advantages, helping Greenlanders survive in an environment where fatty marine diets and extreme cold were the norm. Others, however, may have contributed to the development of certain metabolic diseases.

Greenlandic Inuit traditionally relied on a diet high in animal fats—seals, whales, and fish—rather than carbohydrates. Over generations, their bodies adapted to process this diet efficiently. Previous studies had already linked Inuit-specific gene variants to metabolic traits like fat metabolism, but this new research offers even deeper insights.

One of the most fascinating genetic adaptations lies in a region of chromosome 11, which includes genes such as CPT1A and FADS2. These genes are involved in lipid metabolism and may have undergone natural selection due to the high-fat Arctic diet.

“The traditional Greenlandic diet, rich in fat and protein, has led to natural selection in a genomic region on chromosome 11 encompassing CPT1A and FADS2,” the researchers explain.

However, while these genetic adaptations were beneficial in a traditional Inuit lifestyle, they might be problematic in modern contexts. Today, with more access to Westernized diets rich in processed carbohydrates and sugars, Greenlanders carrying these genetic variants may be more susceptible to obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

This is a stark example of how genetic adaptations that once ensured survival can become liabilities when environmental conditions change—a phenomenon known as “evolutionary mismatch.”

A major takeaway from this study is the glaring inequity in medical genetics. Because most genomic research has focused on people of European ancestry, existing diagnostic tools and treatments often fail when applied to non-European populations.

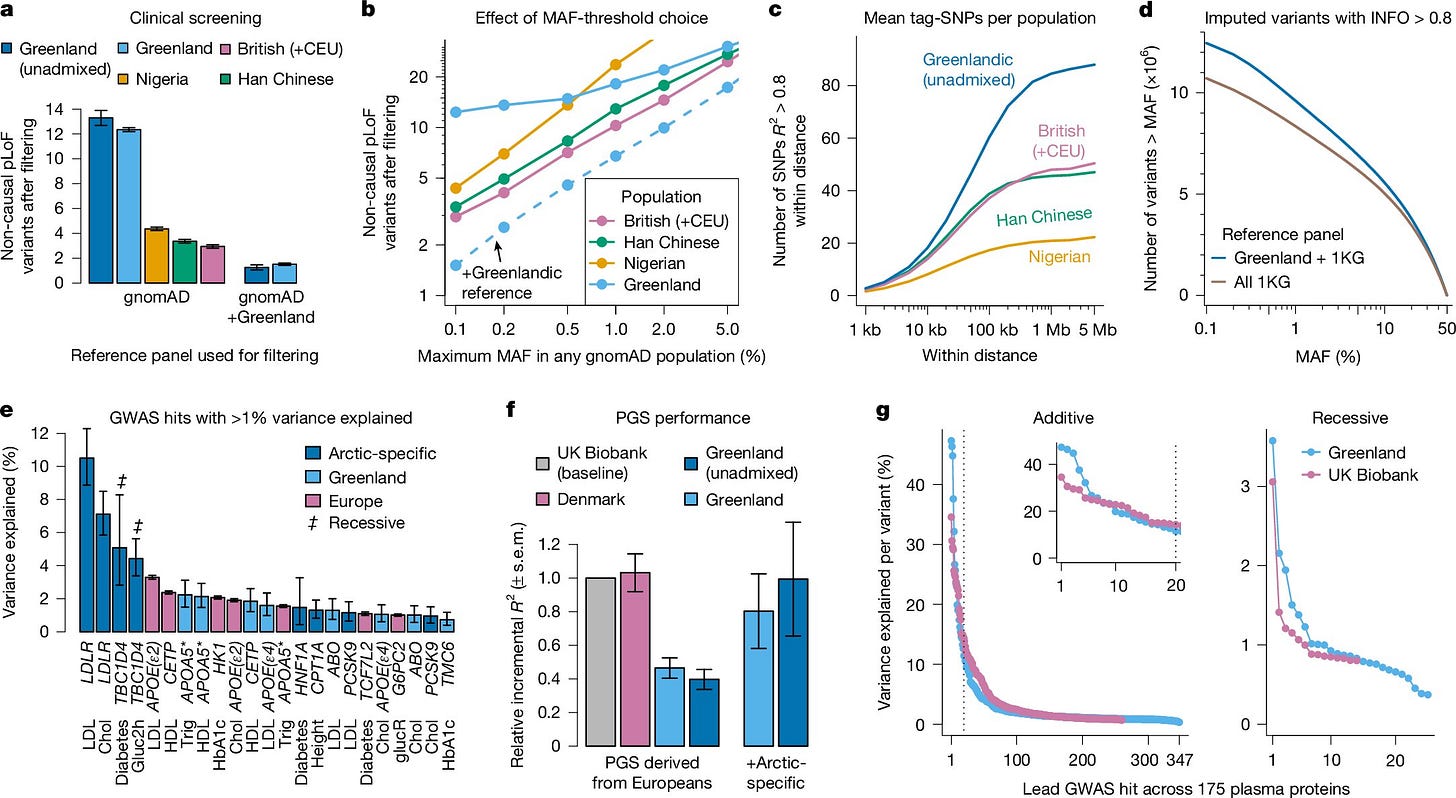

For Greenlanders, this inequity is particularly severe. The study found that standard European-derived polygenic risk scores—a type of genetic tool used to predict disease risk—are only about half as accurate in Greenlanders.

“European-derived polygenic scores for metabolic traits are only half as accurate in Greenlanders as in Europeans, and adding Arctic-specific variants improves the overall accuracy,” the researchers note.

This means that Greenlanders may be misdiagnosed or overlooked when it comes to common diseases, simply because their genetic variants are not accounted for in global medical databases.

Fortunately, the study also provides a path forward. By incorporating Greenlandic genetic data into these models, researchers improved diagnostic accuracy dramatically, even surpassing European models in some cases.

This finding highlights the urgent need to include underrepresented populations in genetic research—not just for scientific completeness, but for real-world medical applications.

Greenland is not as isolated as it once was. In recent generations, migration, urbanization, and increased contact with the outside world have reshaped the genetic landscape. More Greenlanders now have European ancestry—on average, about 25%—which is influencing the frequency of certain genetic traits.

Additionally, as mobility increases, some genetic diseases that were once highly concentrated in specific regions are expected to decline. For instance, the study predicts a drop in the prevalence of recessive disorders that were historically common due to regional genetic isolation.

But even as Greenland’s genetic structure changes, one thing remains clear: the need for inclusion. Without representation in global health research, Greenlanders—and many other Indigenous and underrepresented populations—will continue to face health disparities.

“These results illustrate how including data from Greenlanders can greatly reduce inequity in genomic-based healthcare,” the authors conclude.

The Greenlandic genome is a living record of survival, isolation, and adaptation in one of the harshest environments on Earth. But it is also a case study in how global health research has long overlooked Indigenous populations, to the detriment of both scientific knowledge and medical equity.

This study serves as both a scientific breakthrough and a wake-up call. If precision medicine is truly the future, it must include all of humanity—not just those whose ancestors lived in temperate climates.

For Greenlanders, these findings could lead to better health outcomes, more accurate disease risk assessments, and new medical interventions tailored to their unique genetic blueprint.

And for the rest of the world, this study is a reminder that human genetic diversity is far richer and more complex than we’ve ever imagined.

-

Fumagalli, M. et al. (2015). Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.aab2319

-

Moltke, I. et al. (2014). A common Greenlandic TBC1D4 variant confers muscle insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/nature13425

-

Clemente, F.J. et al. (2014). A selective sweep on a deleterious mutation in CPT1A in Arctic populations. American Journal of Human Genetics. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.005